Former U.S. President Donald Trump appears to be receding from the media. Despite several mentions during the weekly news cycle, and many ongoing developments drawing Trumpian origins, his frequency of reference has been relatively – and predictably – less than during the preceding four years of his Administration. Though his fingerprints remain on many issues, such a decline of attention has ushered several of Trump’s pet peeves and secondary policy interests outside the limelight of the U.S. media – and, simultaneously, the international press as well.

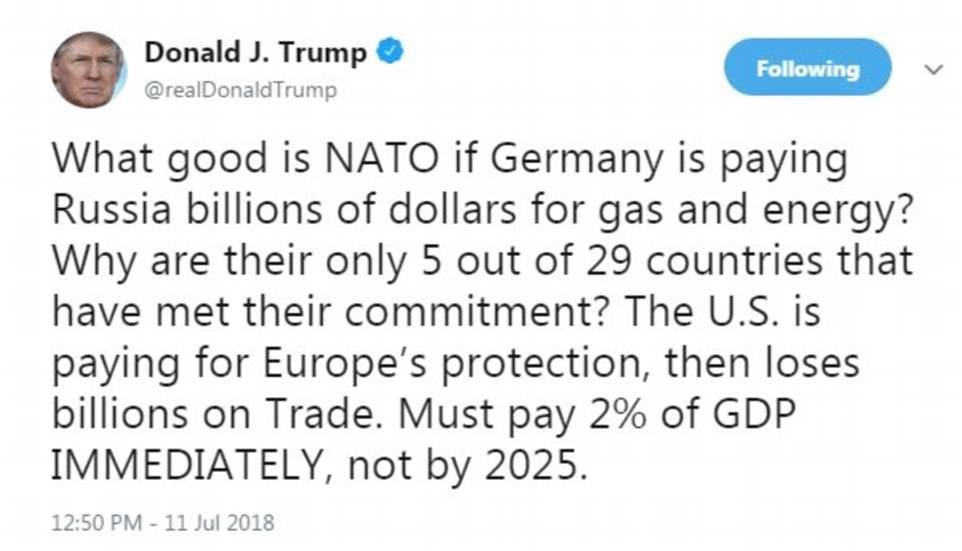

In this regard, one particularly unfortunate loss has been Trump’s passionate criticism of NATO member-states’ defence spending. A notable element of his foreign policy, he memorably and relentlessly criticized allies’ inability to spend 2% of their Gross Domestic Products on national defence – the increased spending yielding greater “military readiness” for the defence of Europe. During the 2016 Presidential Campaign, when Trump first made this critique, only five of then-28 NATO members met this threshold, with Canada (ranked 24) spending a measly 0.99%. Born in the context of Trump’s own domestically-driven effort to raise military spending (enhancing U.S. industry with both domestic and foreign contracts) and retrenchment posture to end “Foreign Wars” (i.e., prolonged campaigns, such as in Afghanistan), he latched onto the issue. It proved to be an electoral lightning rod – clearly illustrating the establishment’s “incompetence” at increasing others’ spending and conveying the appearance of America being “ripped off” by allies. Despite the critiques of his detractors, this perspective was quite legitimate, given NATO Defence Ministers’ 2006 first commitment to the threshold and heads of governments’ 2014 commitment to meeting it by 2024.

Though dismissed by observers under the (somewhat unfair) broadside of Trump’s “distaste” for NATO, his ‘burden sharing’ critique had both merit and appeal, with Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg genuinely echoing his calls. The alliance’s 2% threshold ensures that, as nations increase their GDPs, military spending may rise proportionate to the size of their economies – ensuring both a standardized increase (to avoid ‘free rider’ states) as well as adequate protection. Moreover, amidst Russia’s high military spending – i.e., 3.9% of its GDP in 2019, relatively exceeding the U.S. (growing more lopsided when measured in terms of Purchasing Power Parity) – and greater capabilities (especially, new strategic weaponry), as well as China’s aggressive expansion of its armed forces, increasing its absolute expenditure despite the pandemic, it is imperative for NATO member-states to ensure their military spending remains high. Otherwise, they run the risk of deficiency in both deterrence and combat – the twin elements of collective defence. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 – coupled with Russophile separatism in Eastern Ukraine and Moldova and persistent cyberthreats – illustrate that threats to NATO remain active, with fiscal complacency only inviting peril. Hence, absolute increases in defence spending by member-states are paramount – with investments needing to be made in equipment and troop levels rather than tertiary areas (i.e., servicemember concessions and pensions). Ideally, the “2% threshold” would serve as a floor figure that nations exceed to match continued threats, with Trump’s informal proposal to raise minimum spending to 4% looking fashionable. If this reads like an ‘arms race,’ it is – with good reason. As Crimea illustrated, state survival depends on it.

For all his rhetoric, however, it remains to assess the impact of Trump’s relentlessness on allies’ spending. Based on NATO’s 2019 estimates – made approximately three years into Trump’s term, and before coronavirus recessions artificially raised figures – defence spending per GDP across the alliance was as follows:

As illustrated, nine states (the U.S, Bulgaria, Greece, U.K, Estonia, Romania, Lithuania, Latvia and Poland) met the threshold, an increase from five in 2016 – amounting to, per Secretary-General Stoltenberg, over USD 130 billion in new spending as a result of Trump’s efforts. Though the claim is difficult to causally assess, given potential confounding increases independent of Trump, his efforts certainly whipped members (especially smaller ones) to quicken such pace, else incur the United States’ displeasure. This is evidenced by the four newly-proficient spenders from 2016 levels – i.e., Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Romania: nations in Russia’s geographic orbit by the Baltic and Black Seas, for whom a decline in U.S. commitments would pose an existential threat amidst Russian expansionism. In meeting the threshold, these states shed the image of “free-riders” and justify (per Trump’s standard) the high deployment of NATO battle groups, e.g., the Enhanced Forward Presence, in their territories for anti-Russian deterrence – pursuant to ‘collective defence’. Given the longevity of such a threat and recent proficiency of these states’ spending, Trump may be accorded credit for such increases – quite literally, bolstering the ‘front lines’ of NATO defence.

However, Trump was largely unsuccessful in convincing other allies – Canada included – to make effective increases to meet the threshold in line with their 2024 target. At the Brussels Summit of 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron baldly refused to spend “taxpayers’ money” beyond France’s immediate security threats. However, among such allies, none gained Trump’s ire more than Germany – spending merely 1.38% of its GDP, despite being NATO’s second-largest economy. Amidst other differences – notably, its continued reliance on Russian energy – Trump frequently lambasted Germany for its sluggish increases, occurrent due to its large domestic welfare state (i.e., 25% of its GDP) and post-war aversion to military spending, the latter due to historical trauma of the Nazi regime’s militant memory. Though increased German spending would yield an extra USD 23 Billion – invaluable for NATO defence – it remains unlikely in the near future, given the convenient excuse of a “coronavirus recovery” and the Biden Administration’s lack of advocacy on the issue. As a consequence, the 2024 target of 2% spending alliance-wide is sure to be missed.

For Canada, though Trump’s pressure may no longer exist, the need to jolt defence spending to meet the 2% threshold (i.e., USD 34.7 Billion annually, per its 2019 GDP) is urgent. Amidst potent Russian contests over its Arctic possessions, along with some from allies (i.e., Denmark and the United States), and a hostile Indo-Pacific on its Western flank, Canada’s territorial integrity will depend upon a massive acquisition of (primarily naval) assets for national defence. Simultaneously, these will be essential to meeting Canada’s NATO deployment commitments, e.g., Operation Reassurance. So far, rather than a lack of fiscal capacity to spend such sums, its lethargy in this crucial realm stems from a stymied procurement process – e.g., the cost fiasco over Canada’s Surface Combatant project – and increasing though, thankfully, marginal calls from some on the political left to reduce military spending in favour of social programmes for the welfare state. While contempt for the former is accepted, the latter frequently rears its naïveté in public opinion – notably, at the recent NDP Policy Convention. More insidiously, it conforms with political leaders’ self-interest, given the exasperating brokerage of welfare-state rents (e.g., Canada’s Equalization and transfer payments) that characterize social democracy and the absence of a pro-military constituency in federal politics (unlike the U.S). Momentarily, so long as crises are distant, Canada appears unwilling to climb out of its defence spending default, and remains ‘in the Red.’

Nonetheless, the principle of meeting foreign commitments and realist prudence – recognizing the positive deterrent value of a robust capacity for violent force – must prevail, and Canada must meet 2024’s target of 2% (or, at the very least, not achieve it too late); if necessary, in the view of this author, spending less on social programmes and welfare for this purpose. Doing so would reduce insecurity, and reverse the nose-diving descent of Canada’s standing in the world – far greater than Trump ever could.

Photo: @realDonaldTrump on July 11, 2018, by Donald J. Trump, via the Daily Mail. Open domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.