The end of the Vietnam War forced over one million Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian citizens to flee their war torn countries on ships which set sail around the world. After managing to survive years of warfare and dangerous journeys across the seas in shocking conditions, many of these so called ‘Boat People’ were turned away at the shorelines. As news of their plight spread, many Western nations pledged their assistance, and between 1979 and 1980 Canada accepted a record 60,000 refugees. The United Nations pronounced 2014 as the worst year for displaced people as the number topped 50 million for the first time since WWII. Yet, reports show that in 2013 Canada accepted just over 13,000 refugees.

The end of the Vietnam War forced over one million Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian citizens to flee their war torn countries on ships which set sail around the world. After managing to survive years of warfare and dangerous journeys across the seas in shocking conditions, many of these so called ‘Boat People’ were turned away at the shorelines. As news of their plight spread, many Western nations pledged their assistance, and between 1979 and 1980 Canada accepted a record 60,000 refugees. The United Nations pronounced 2014 as the worst year for displaced people as the number topped 50 million for the first time since WWII. Yet, reports show that in 2013 Canada accepted just over 13,000 refugees.

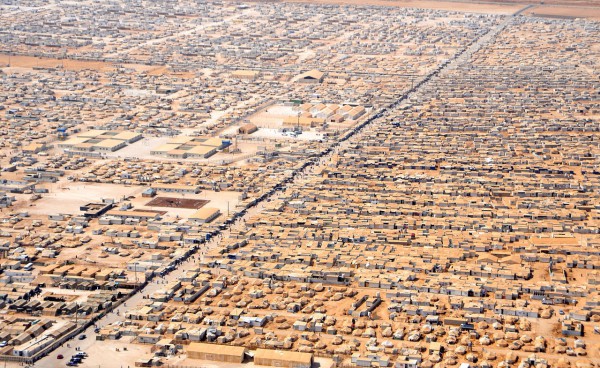

June 20 marked World Refugee Day and its significance was highlighted with the highest number of asylum seekers documented since the end of the Bosnia Herzegovina conflict in 1992. The UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency, data recorded around 866,000 applications lodged in 2014, a 45% increase from the previous year. The conflicts in Syria and North Africa have driven thousands of refugees across the Mediterranean, with often unseaworthy boats several of which have sunk before reaching land. Many of the refugees are seeking asylum in the member states of the European Union, which has seen an 86% rise in applicants from one year ago.

As a response to the April drownings of 900 migrants in the Mediterranean, the EU proposed to take in 40,000 asylum seekers, and the recent summit looked to address the co-ordination and distribution of this large influx into the existing population. Controversy and opposition arose when it was revealed that part of the plan included the introduction of immigration quotas across the EU. The redistribution and sharing of refugees would no longer be voluntary. Each member state would be bound to a mandatory figure.

Countries such as Germany, Sweden, Italy and Greece which have been receiving the majority of refugees are strongly in favour of the quotas that would alleviate their economic strains and create a more equal plain. However, the quota system has faced serious criticism from many other member states with French President Francois Hollande stating “one cannot talk of quotas, there can’t be quotas for these migrants,” adding that quotas for “the right to asylum” would not make sense.” The strong divisions led to the EU interior ministers’ remaining deadlocked, with the issue being pushed onto the agenda of a June 25-26 leaders’ summit.

It has also been proposed that the member states at the first point of entry, primarily Italy and Greece, should use support from the European Union budget to increase surveillance of their external borders in order to prevent these illegal and dangerous crossings. Efforts to increase restrictions are most often attributed to the economic factors involved in regulating the number of immigrants and refugees admitted into country over a given period of time. The strain on social services essential to the new arrivals, as well as issues of security and the impact on the workforce are concerns facing European governments. Racism and xenophobic attitudes have also become a factor for many European countries who’ve had to deal with the arriving masses of refugees.

Germany, the country that receives the highest number of refugees in the world, has seen a dramatic rise in protests and violent attacks against asylum seekers, with 150 incidents reported in 2014 alone. The second highest receiving EU member state, Hungary, recently announced its intention to build a 175km long and four metre high wall to effectively close its border with Serbia, the country which many migrants and refugees travel through on route to Western Europe. The plan has shocked and outraged many, however the nation’s Foreign Minister defended the construction stating “Hungary could not wait for the EU to find a solution to immigration”. These negative sentiments were echoed by the former Danish Prime Minister, who spoke openly concerning his opinion on the damage large numbers of refugees would have on Denmark’s economy and ‘societal model’. He cited the fact that the number of asylum seekers had quadrupled since 2011 and almost 50 percent of people in Denmark with a non-Western background, are on some kind of public support.

Of the top refugee receiving countries, the UNHCR annual asylum trends report in 2014 ranked Canada fifteenth. This is a notable decline from a record fifth position five years prior, which can be attributed to a 2013 overhaul of the refugee determination system. The statistics are troubling given that many countries ranked above Canada, such as Sweden, have significantly smaller populations yet manage to receive much higher numbers of refugees.

Of the top refugee receiving countries, the UNHCR annual asylum trends report in 2014 ranked Canada fifteenth. This is a notable decline from a record fifth position five years prior, which can be attributed to a 2013 overhaul of the refugee determination system. The statistics are troubling given that many countries ranked above Canada, such as Sweden, have significantly smaller populations yet manage to receive much higher numbers of refugees.

Canada’s admittance of tens of thousands of refugees following the Vietnam War faced opposition from those concerned over the multi-million dollar price tag, the possibility of increased land and gas prices as well as a rise in unemployment. Their predictions proved unfounded, as the nation’s GDP continued to rise in the years following and the outpouring of support marked Canada as a leader in the fight for human rights.

The history of Western interference in the majority of today’s war torn countries begs the question as to the level of responsibility the West bears in solving the current refugee crisis. As the wealthiest nations in the world, there are the means available as well as the systems in place to support those in need. Over a century of influence in developing nations’ political and economic landscapes is not easily set aside, as the lasting effects of propped up dictators, arbitrarily drawn borders, and the exploitation of natural resources are still being felt by much of the world’s population.