In 1995, Canada used its maritime force to intercept and seize a Spanish fishing vessel off the Atlantic coast of Canada. Dubbed the Turbot War, this maritime conflict provides a unique instance where Canada acted unilaterally to enforce its interests when the applicable multilateral institution, the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO), failed to do so. This use of unilateral force strengthens the argument for the need for Canada to maintain a capable maritime force across all of its coasts. Additionally, as Canada’s position in the Arctic grows more precarious, relying on multilateralism will likely not suffice. As owners of the world’s largest coastline, Canada’s ability to protect its waters is an imperative and daunting task. The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), which was once the world’s fifth largest naval force after the Second World War, is now arguably less capable than the Bangladeshi Navy.

Multilateralism fails, Canada responds

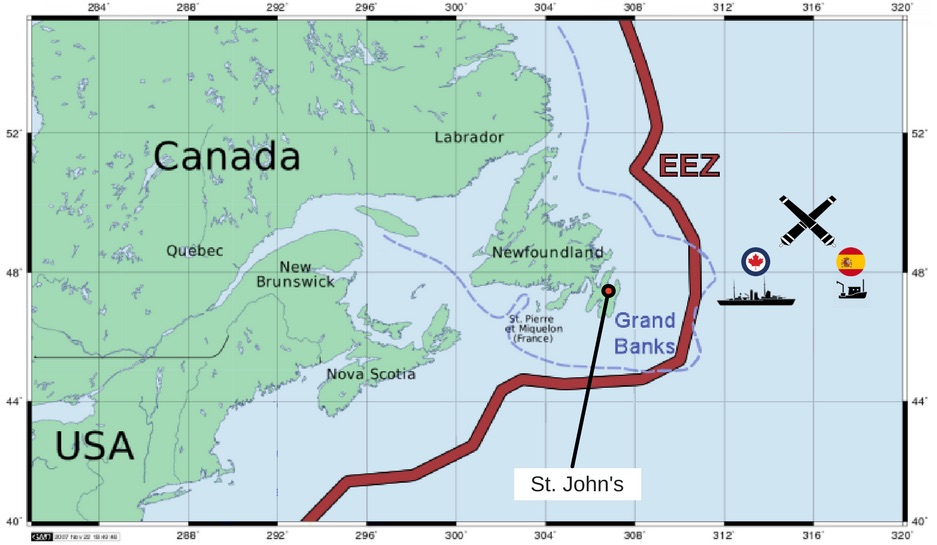

The Turbot War took place off the coast of Newfoundland in the Grand Banks, a nutrient rich fishing ground, just outside of Canada’s territorial waters. Foreign fishing fleets operating in the international fisheries were contributing to a depletion of fish stocks within Canadian waters and threatened to adversely affect the Canadian maritime economy. In response to this foreign overfishing, Canada successfully lobbied NAFO to implement provisions and quotas on foreign fleets operating in the area to curb the exploitation of marine populations. NAFO, an intergovernmental organization, was established to meet the provisions set forth in Article 63 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which calls on coastal states to cooperate in protecting fish stocks outside of national maritime boundaries. NAFO’s jurisdiction lies in the Northwest Atlantic and seeks to ensure intergovernmental cooperation in regulating fishery resources. The Grand Banks, an international maritime area beyond the national boundaries of Canada, falls within this jurisdiction. However, in 1995, NAFO failed to successfully enforce measures preventing Spanish fishing vessels from exceeding prescribed quotas.

When Spanish fishing fleets ignored the quotas and jurisdiction of the NAFO provisions, Canada reacted with an extra-judicial maritime force exceeding their own 200nm Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) boundary. Canada dispatched the HMCS Gatineau, a Restigouche-class naval destroyer, and armed Canadian Coast Guard vessels to intercept the infringing Spanish fishing fleet on the Nose of the Grand Banks. A pursuit ensued, and the Canadian coast guard ships fired warning shots over the bow of the Spanish fishing ship, the Estai. The Estai eventually surrendered and was escorted back to St John’s for the detention and trial of the ship’s captain. The seizure prompted Spain, with the support of the European Community, to ready warships in response to Canada’s aggression. However, before the Spanish Armada could reach Canadian water, the crisis was resolved at the negotiating table.

While a blunt and aggressive action taken against an allied NATO flagged ship, this bloodless maritime  confrontation can largely be considered a Canadian success. The result of this unilateralism was both Spanish adherence to NAFO’s jurisdiction and the passage of new legislation that better protected Canadian national and environmental interests. Most notably, as a direct result of Canada’s extra-judicial use of force, NAFO implemented more effective enforcement mechanisms. These improved mechanisms included a more robust satellite surveillance of the fisheries area and placement of inspectors on board ships fishing in the NAFO jurisdiction area. Thus, Canada’s use of force strengthened the applicable multilateral institution and aligned it more closely to Canadian interests.

confrontation can largely be considered a Canadian success. The result of this unilateralism was both Spanish adherence to NAFO’s jurisdiction and the passage of new legislation that better protected Canadian national and environmental interests. Most notably, as a direct result of Canada’s extra-judicial use of force, NAFO implemented more effective enforcement mechanisms. These improved mechanisms included a more robust satellite surveillance of the fisheries area and placement of inspectors on board ships fishing in the NAFO jurisdiction area. Thus, Canada’s use of force strengthened the applicable multilateral institution and aligned it more closely to Canadian interests.

Multilateral governance in the Arctic

Based on the success of this use of maritime force in 1995, it is clear that Canada must maintain the ability to act unilaterally along all of its coasts. Currently, Canada relies heavily on multilateral forms of governance in the Arctic, most prominently the Arctic Council. As the threat to Canadian coasts is most salient in the changing and volatile Arctic region, this reliance on multilateral forms of governance over maritime territory can be troubling. The Arctic Council, an intergovernmental institution, has a similar mandate to NAFO stressing interstate cooperation. However, as seen in the Turbot War case, relying on multilateral institutions to protect Canadian interests appears inadequate. We may see a similar failure of the Arctic Council multilateral cooperation to safeguard Canadian interests in the region. Therefore, Canada’s ability to act unilaterally in the Far North is of specific importance.

Canada’s maritime deficiencies

Presently, the RCN is in a poor state. Last year’s decommissioning of the RCN’s Iroquois-Class HMCS Athabaskan was the end to Canada’s destroyer fleet. Plagued by budget cuts and neglect, Canada no longer possesses the maritime force it once had, and as a result, has lost the majority of its maritime capabilities. Unfortunately, the RCN’s inadequacies are most pronounced on Canada’s most vulnerable front. The operational difficulties involved with operating in an Arctic environment exacerbates the deficiencies of Canada’s Arctic maritime capabilities. Without an updated icebreaker fleet and an insufficient presence of permanent Arctic naval bases, the capability of Canada’s maritime force remains questionable. Canada’s ability to project unilateral maritime force in the region is an important question that must be assessed.

Utilizing multilateral institutions is advantageous for asserting Canadian interests, however, cannot be relied upon completely. Multilateralism failed to protect Canada’s Atlantic coast in the 1990s, and in this case, the responsibility fell on Canadian maritime power to assert and protect its own interests. Moreover, the Turbot War proved that Canadian interests in multilateral forums can be strengthened through its use of force. However, Canada’s navy as a whole is slipping into deeper disarray and its maritime Arctic capability lags far behind as a result. Thus, it is critical that Canada develops an adequate maritime force to respond to the growing threats to Canadian interests in the volatile Far North.

Photo: Restigouche-Class Frigate’s on Patrol in the Atlantic via Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain. Photo courtesy of U.S. Defense Imagery.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.