Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, between US $50 billion to US $100 billion dollars in the form of foreign aid flowed into Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in the 1990s. The goal was to promote the development of civil society and soften the transition from communism to capitalism. Many of the NGOs created in this period were women’s organizations. Despite the proliferation of women’s organizations, there has been a rejection of feminism in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, encouraging the return of women to the domestic sphere. The emancipation of women has been blamed for the disintegration of the traditional family unit. In popular discourse, the traditional role of women as wives and mothers is often glorified and tied to an idealized national past.

Often, when we think of feminism, our thinking is couched in broad general terms such as equality between men and women, abolishing discrimination in the workplace, or ending violence against women. However, our understanding of the movement is coloured by an ‘end of history’ perspective, taking for granted that economic modernization and liberal democracy engenders greater individualism, consumerism, homogeneity, and globalization. Through exploring the historical legacy of Cold War tensions and socialism, we can come to a better understanding of what feminism means in Eastern Europe and why the mainstream ‘one-size-fits-all’ brand of feminism has yet to take root in Eastern Europe despite the best attempts of various organizations.

In professor Kristen Ghodsee’s (2010) article entitled “Revisiting the United Nations decade for women: Brief reflections on feminism, capitalism and Cold War politics in the early years of the international women’s movement”, she explains how the divisions between the Eastern Bloc and the United States coloured the three UN women’s conferences held in Mexico City (1975), Copenhagen (1980), and Nairobi (1985) during the United Nations Decade for Women.

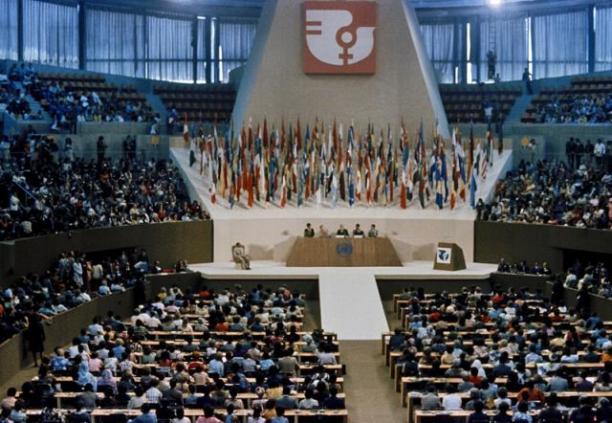

The meeting in Mexico City (1975) at the time was the largest meeting in history to deal with women’s issues, with 125 member states sending official delegations. U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the National Security Council of the US (NSC) opposed sending First Lady Betty Ford to the Mexico City Conference, contrary to the wishes of Henry Kissinger’s wife Nancy Kissinger, the Israeli Prime Minister Leah Rabin, and the First Lady herself. Kissinger and the NSC wanted to avoid linking women’s issues to an anti-capitalist agenda. This instance demonstrates how state affairs and political manoeuvring took precedence over women’s issues. Similarly, women sent to the Conference from Eastern bloc countries were also heavily controlled by male politicians at home.

The Mexico City conference is interesting because it illustrated the divide between the Westernized interpretation of feminism and the brand of feminism favoured by the Eastern bloc. For example, the U.S. focused on legal barriers to equality: workplace discrimination, education attainment, and women’s participation in politics. The women from the Eastern bloc pushed for a ‘peace agenda’, reasoning that legal equality with men had already been achieved in their respective countries and that the Conference should be an opportunity for women to discuss the same world issues men debated in the UN such as nuclear proliferation. The Eastern bloc countries also advanced the essentialist idea that women were inherently less violent than men. This essentialist legacy carries over to today, with the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 reinforcing representations of women as particularly vulnerable to violence and inherently more peaceful.

Five years later, during the Copenhagen Conference (1980), the same divisions emerged again, with many NGO participants leaving convinced that the international women’s movement had been damaged. The U.S. government wanted to focus narrowly on inequalities between men and women, avoiding any discussion of economic systems. However, the official Copenhagen Conference document acknowledged that countries with centrally planned economies saw further advancement of women in areas such as health, education, employment, and political participation. According to one participant, the voting pattern at the conference made it clear that “the male establishment does not take women seriously… No government or group really wants anything for women enough to compromise on other issues. Women’s conferences, therefore, reflect the UN at its worse.”

Governments used the Conference as a platform to promote their own political agendas. Several draft resolutions went to a vote because Northern bloc countries resented the language used by Southern bloc countries. For instance, Resolution 11 called for women’s participation in the “struggle against colonialism, racism, racial discrimination, foreign aggression and occupation, and all forms of foreign domination.” Resolution 11 was interpreted as an attack on U.S. military interventions. Another contentious issue involved reports on the condition of Palestinian women, with Israel arguing that Zionism did not constitute racism but national liberation of the Jewish people, and Lebanon asserting that “Zionism was not a liberation movement but racist in both its structure and practices.”

Copenhagen illustrated hidden gender biases, given that women’s issues were perceived by delegations as apolitical and noncontroversial. Parties assumed that women’s concerns were a ‘luxury’ to be dealt with later second to ‘hard’ issues such as the situation in Palestine or apartheid. However, countries such as Albania believed that the true cause of inequality between men and women was “the division of society into oppressors and oppressed.” Hence, it would be narrow-minded to separate women’s issues from heavily politicized topics such as neo-colonialism, apartheid, or economic inequality.

“Nobody would have admitted it, and it definitely would not be said by anybody from the U.S. delegation, but it certainly did seem that women had at least more legal equality in the socialist bloc.”

– A member of the U.S. delegation to Mexico City and Copenhagen

The Nairobi Conference in 1985 was considered the most productive. A final document the “Forward-Looking Strategies for the Advancement of Women” was adopted unanimously and a five-year action plan that outlined concrete plans for women’s advancement was adopted. However, tensions were also high. On the first day of the Nairobi conference, a group of Soviet bloc countries sent a letter to the President of the Conference accusing the U.S. of undermining the goals of the UN Decade for Women by being a war-mongering nation.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Cold War had been won by the West. This sentiment influenced the international women’s movement agenda, discrediting critiques of capitalism and its role in perpetuating inequalities. The standard Western view of feminism has influenced the European Union’s agenda for gender equality, which focuses on workplace discrimination and legal barriers rather than underlying political economic causes.

However, as Professor Kristen Ghodsee notes, instead of questioning the economic system, which exacerbates competition between men and women and concentrates wealth in the hands of oligarchs, Western feminist organizations are content to advocate equal opportunity and anti-discrimination laws that are difficult to enforce. In order to understand the resistance to feminism in Eastern Europe, it is important to study the evolution of the international women’s movement agenda against the backdrop of Cold War tensions and differences between Western and Socialist feminists.