Across Asia and beyond, the weight of China’s rise is being increasingly felt, shifting the orbits of regional actors and placing the global economy on an increasingly eastern tilt. At the moment, China is the largest economy in the world by purchasing power parity (PPP), the second largest in overall measurements of gross domestic product (GDP), and is soon to become home to the world’s largest population centre. Despite this enormous economic footprint, it is only in recent years that China has sought to become a stakeholder in global governance. This process received a renewed sense of impetus with the arrival of Xi Jinping.

Since he rose to power in November 2012, President Xi’s policy initiatives have revealed a grand vision of what China should be. In the last few years he has wasted little time in seeking to transform Beijing into a key hub within the international system. This can be seen as China’s response to the threat posed by climate change, increased commitments to United Nations peacekeeping forces and in hosting international sports competitions. China under Xi is a nation increasingly engaged with the world, while also seeking to advance its own interests. This is also evident in the sphere of international finance and institutions, where China has launched a wave of initiatives, which are both challenging and complementing the post-1945 Bretton Woods system. Perhaps the best example of this is the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

China as an institutional founder?

There are few areas where China has been more dissatisfied with its position globally than in the world of international finance. In spite of its attempts to reform, the International Monetary Fund and World Bank remain dominated by the United States and Europe, much to the chagrin of developing states, and especially China. Within the Asia-Pacific, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which has a similar structure to the World Bank and has been in existence since 1966, has been the leading financial institution. There, the majority stakes are controlled by Japan and the United States, with the ABD president always being from Japan. The AIIB is the first international institution in which China is the principal state and major stakeholder. It represents a step forward for Beijing to secure a new position for itself within the international order but outside the contemporary post-1945 system.

According to current estimates, Beijing will be the dominant state in the institution with a 30.34% shareholding in the AIIB, whose initial capital worth is estimated at $50 billion, but is expected to increase to $100 billion by year’s end. As a founding member, China has the largest share of the vote for the institution at 26.06%, and the AIIB will be headquartered not in New York or Geneva but in Beijing.

The president of the World Bank, Jim Yong Kim, along with leading figures within the ABD, has welcomed the creation of a China-led financial institution. However, behind the diplomatic discourse, there exist real concerns in Washington and Tokyo surrounding the dilution of Bretton Woods institutions such as the World Bank. Further to this point, there are concerns regarding the overall transparency of the AIIB vis-à-vis environmental and corruption standards. These concerns play into wider fears relating to the increased economic influence of China and the relative decline of US influence in the Asia-Pacific region.

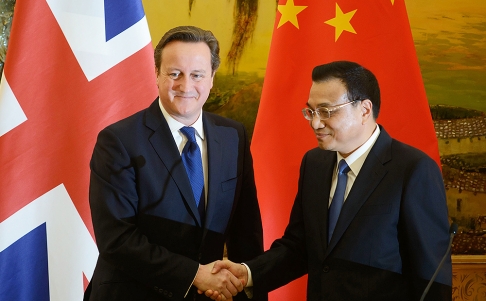

These concerns in Tokyo and Washington have been exacerbated by the international reaction to the AIIB. On the diplomatic front, the AIIB represents a major endorsement of China as an institutional founder and a major strategic misstep by the United States. Over twenty-one Asian nations, including India, a nascent US partner in Asia, have signed up to become founding members. Even in the face of diplomatic opposition from the United States, key regional and international allies such as the United Kingdom, South Korea and Australia have signed up to join the AIIB, bringing the total number of states to 57.

One Belt, One Road

The AIIB represents an individual component of a far larger strategy that would see China at the heart of a network of economic institutions and initiatives, returning Beijing to its historic role as the Middle Kingdom.

Announced in October 2013, during President Xi’s trip to Central Asia, the One Belt, One Road program represents the grand strategic initiative under which Chinese foreign policy is operating. The AIIB, as part of this program, is designed to fund the infrastructure investment that will allow the two components of One Belt, One road to come to fruition.

The land-based Silk Road Economic Belt will seek to reconnect China with the markets of Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia. Particularly within Central Asia, Beijing is investing heavily in dilapidated Soviet infrastructure, and in spite of cordial ties on the surface, One Belt, One Road has the potential to undermine Russia’s traditional influence in the region.

Meanwhile, the oceangoing Maritime Silk Road will connect Chinese trade with the nations of South East Asia and the Indian Ocean. Within India, the strategic inroads made by China in Sri Lanka have not gone unnoticed. The 4, 000 acre Hambantota Port would service rising Chinese naval ambitions while also becoming a nexus for Chinese exports into the Indian sub-continent and the lucrative Persian Gulf.

Above all else the Maritime Silk Road would build upon the growing strategic relationship with African states. Even as the United States is boosting its counter-terrorism cooperation with Kenya and Ethiopia to combat Al-Shabaab, the new African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa was financed entirely by Beijing, symbolizing China’s growing presence on the continent.

China as the Middle Kingdom

If successful, Beijing estimates the One Belt, One Road initiative will add an additional USD $2.5 trillion to China’s trade in the next decade. In context that is more than the total value of China’s exports in 2013, thereby cementing its status as the world’s largest trading nation. This gives China unprecedented financial influence that has not been seen internationally for over two hundred years.

Through One Belt, One Road, Beijing is seeking to re-establish an identity that first emerged during the Han Dynasty of China as the Middle Kingdom; the centre of international trade, commerce and civilization. Thus, it is no small coincidence that states in Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East are the subject of such focus from Beijing. Under the Ming and Qing Dynasties, China was a major trading partner and a sought-after destination for all these regions. The attempt by Beijing to create a contemporary successor to the Silk Road of antiquity draws heavily on China’s trading past.

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, designed to mirror western institutions, is indicative of China’s increasing financial influence in the Asia-Pacific and beyond. The question now is whether China will seek to capitalize on this economic power and turn it into political leverage.