100 Days

On April 6, 1994, President Habyarimana was killed after his plane was shot down over Kigali. Though it still remains unclear as to who the assassins were, both the RPF and Hutu extremists took the opportunity to point fingers and blame one another. Within an hour of Habyarimana’s murder, roadblocks were set up by the Presidential Guard with the help of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) and the Interhamwe and Impuzamugambi Hutu militia groups, and the massacre of Tutsis and moderate Hutus began. On April 7, soldiers killed ten Belgium UNAMIR peacekeepers tasked with protecting the moderate Hutu Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, who was subsequently murdered. After the systematic culling of most of the political opposition, an interim government was established and Hutu extremists took control of the state.

Rwandan media outlets also played a significant role in inciting the genocide. The dominant Radio Television Libre de Mille Collines (RTLM), a racist anti-Tutsi radio station established in 1993, broadcasted a list of people whom listeners were encouraged to find and kill. Not only were government forces and militia groups responsible for the killings, but average Rwandans were also involved, either willingly or at the demand of Hutu hardliners. Many Hutus hacked their Tutsi neighbours to death with machetes, a common household tool in Rwanda, while those who fled were driven into public buildings such as churches, schools, and stadiums and killed en masse.

For 100 days, the genocide continued virtually unabated. As a result, over 800,000 Rwandans were killed, most of whom were Tutsis. The RPF, who had been fighting the Hutu forces since the outbreak of the conflict, finally took Kigali in early July, essentially ending the genocide. However, violence still persisted as Tutsi rebels committed reprisal killings against Hutus and some extremist Hutus continued to massacre Tutsis in refugee camps. Finally on July 4, RPF forces established full military control over all Rwandan territories and the conflict was brought to an end, though millions of Rwandans remained displaced after fleeing the fighting, and a deadly cholera epidemic spread through refugee camps killing many more.

Looking the Other Way

As the conflict came to an end and the extent of the violence became apparent, the international community had to cope with the consequences of inaction in Rwanda. There were calls for intervention at numerous points before the conflict and throughout its duration, yet there was no substantial effort made to quell the violence. UNAMIR, which had been on the ground monitoring the ceasefire since October, 1993, was aware of the deteriorating security situation before the genocide occurred, with UNAMIR head Jacques-Roger Booh Booh contacting UN headquarters months before the genocide began to relay his concern over increasingly violent clashes between Tutsis and Hutus and reports of Hutu militias stockpiling weapons.

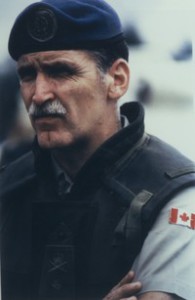

Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire, the UNAMIR military commander, also contacted UN headquarters in early January, 1994, after an informant had notified him of weapons stockpiling and the possibility that Hutu militias were plotting a “Tutsi extermination”. General Dallaire’s request to conduct raids on arms caches around Kigali was denied by his superiors in New York. Further requests to strengthen UNAMIR’s mandate and increase the number of troops were also denied, and when the fighting actually began in April, the UN Security Council voted to withdraw most of the 2,500 peacekeeping forces in Rwanda, leaving Dallaire with a paltry force of 270. Despite the pleas from UNAMIR’s command, the UN remained wary of further involvement, and the total lack of military force coupled with the mission’s narrow mandate on the use of force left UNAMIR with very limited power to stop the onslaught once it began.

The UN and the international community as a whole bears some responsibility for the high number of casualties as there were virtually no efforts to stop the genocide. Many states actually danced around using the term ‘genocide’ to characterize the conflict, as doing so would compel them to intervene under the terms of the Genocide Act. Despite the international media being present in Rwanda and covering the extent of the violence, this did little to push the international community to respond. It wasn’t until mid-May that the UN finally declared the crisis a ‘genocide’ and the Security Council agreed to bolster UNAMIR forces by 5,500 troops and 50 armoured vehicles, though bureaucratic squabbling didn’t see these troops actually make it to Rwanda until October, long after the conflict had ended.

The international community’s dismal efforts to stop the Rwandan genocide have in retrospect been labelled a colossal failure, with the consequences not only being the utter destruction Rwandese civil society but a severe tarnishing of the UN’s reputation as a diffuser of global conflict. In response to this realization, the UN decided to finally give Rwanda the attention and aid it merited, with a focus on justice and retribution for the crimes committed. As a result, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established on November 8, 1994, with the aim of prosecuting the criminals responsible for the genocide and putting Rwanda on the road to recovery and reconciliation. In Part III, this series will conclude with a look at the ICTR and an analysis of Rwanda’s present-day situation.