On May 26 this year, dramatic footage emerged via a CNN news team aboard a United States Navy P8-A Poseidon surveillance aircraft, which highlighted the increased tensions in the South China Sea. As the aircraft approached the Subi and Fiery Cross reefs in the disputed Spratly Islands chain, fleets of Chinese dredgers and ships were visible on the horizon and on surveillance equipment. These vessels are involved in the reclamation of submerged coral atolls, turning them into islands capable of hosting long-range aircraft. Within moments of the arrival of the P8-A Poseidon, CNN recorded in detail the challenges made by Chinese radio operators ordering the immediate departure of the Americans.

At one point, exasperated by the continued presence of the US Navy’s newest surveillance aircraft, the exchange grew hostile with the Chinese operator raising his voice. According to the aircraft’s commander, their P8-A has increasingly been tasked with surveying China’s rising presence in the South China Sea. The more sophisticated the island installations have become, the more hostile the Chinese radio challenges have been.

China’s role in regional tensions

Beijing has long asserted claims to sovereignty in the South China Sea, the best known of which has its origins in the Republic of China’s (1911-1949) Nine-Dash line. However, in recent years the narrative from Chinese officials has begun to change. In September, when Vice Admiral Yuan Yubai spoke at the International Sea Power Conference in London, he raised concerns by stating, “The South China Sea, as the name indicates, is a sea area that belongs to China. And the sea from the Han dynasty a long time ago where the Chinese people have been working and producing from.”

The Vice Admiral is not alone in making this assertion. A cursory glance at Chinese state media during the 2014 crisis with Vietnam over the Haiyang Shiyou 981 oil rig reveals a similar discourse. Due to China’s unique longevity as a polity, Beijing is increasingly basing its claims on the Han dynasty, which governed China from 206 BC–220 AD. Beijing is thus basing the legitimacy of its claims on a historical longevity with which few states can compete. However, this model has no precedent under international law.

Yuan’s comments in London did little to alleviate concerns regarding Beijing’s intentions in a region with multiple actors claiming sovereignty. This in a waterway brimming with international trade bound for some of the largest economies on the planet.

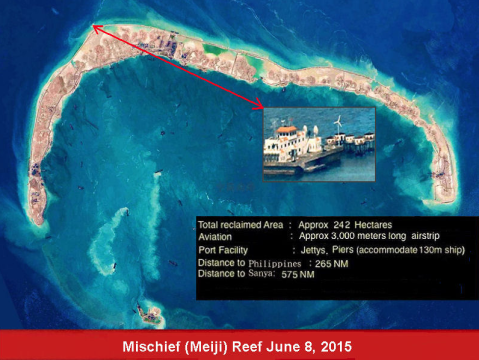

According to the Pentagon, China has reclaimed 2,900 acres of land at seven different reefs in the Spratly Islands chain since December 2013, with installations on the Mischief, Fiery Cross and Subi reefs being well-publicized.

Developments in the Spratly Islands

Closer observation of these three individual reefs highlights the scale of the land reclamation currently under way, for which the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) is an invaluable source. In the heart of the South China Sea, AMTI calculates that 2.7 million metres of Fiery Cross reef has been reclaimed since December 2013, making it now 11 times its original size. The coral atoll is now equipped with a new airbase with early warning radar and a runway over 3,100 metres long. This facility is capable of accommodating a wealth of Chinese long and medium-range fighter and transport aircraft.

A similar 3,000 metre runway is visible on Subi Reef, where over 3.9 million metres has been reclaimed. In images acquired by AMTI, advanced installations such as helipads, loading piers and satellite communications arrays are clearly visible amidst the wealth of construction take place. As early as 1997, the reef was equipped with no more than two wooden barracks on poles, but now it represents one of China’s most ambitious installations less than 16 miles from the Philippines-governed Thitu Island.

As a final example, Chinese land reclamation on Mischief Reef has seen over 5.5 million metres recovered. A major fortified sea wall is under construction which, according to analysts, could turn the reef into a harbour basin capable of accommodating vessels from the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). Of the three islands it is the base on Mischief which brings China into the very heart of the Spratly Islands chain.

Beijing has long sought to garner increased influence in the South China Sea, with its actions revealing a deep dissatisfaction with the state’s current strategic position. The larger atolls and islands were secured in the 1970s by Vietnam and the Philippines, leaving China, a relative latecomer, with territory that remained underwater even at low tide. The land reclamation program unquestionably seeks to reverse this by expanding the submerged reefs into sophisticated installations. It clearly forms part of a larger pattern aimed at giving China greater weight in the domain of maritime power projection.

Beijing’s growing maritime strength

Since coming to power, President Xi Jinping has sought to continue the transformation of the PLAN into a blue-water force with global reach. The aircraft carrier Liaoning, represents the beginning of China’s carrier forces, with two more known to be under construction. Further to this, in July, Chinese vessels conducted war games and live fire drills in the South China Sea. Subsequently in August, five Chinese vessels arrived off the coast of Alaska, coinciding with a visit by President Obama to the state to discuss climate change.

Finally, as reported in the People’s Daily, Beijing seeks to complement the land reclamation program and its naval expansion with a third pillar. The Very Large Floating Structure (VLFS) program will see the construction, as the name suggests, of large artificial platforms as long as 3km, mirroring a concept proposed but rejected by the United States in 1990 during Operation Desert Shield in the Persian Gulf. The VLFS would serve in a disaster relief capacity, but due to its sheer size, it could also operate as fleet logistics stations, as well as floating semi-mobile airports for the People’s Liberation Army. Indications suggest the first VLFS is already being built at a dry dock in Caofeidian near the city of Tianjin.

Through these pillars, China is seeking to achieve a maritime role in the region beyond any previous capabilities. The scale of the projects being undertaken suggests that in the near future China seeks to become the principal maritime power amongst the claimant states in the South China Sea. If successful, China would be in a position to challenge the status quo and achieve the strategic position Beijing sees as befitting its economic power.

Shifting perceptions in Washington

Given the recent moves by Beijing, some quarters in the United States are increasingly viewing Beijing’s pursuit of strategic parity in the South China Sea through the prism of aggression. Shifting perceptions in Washington could lead China to be viewed not simply as a rising economic competitor but as the US’ principal strategic rival in the Asia-Pacific region. In this respect, President Xi’s September visit to the US failed to yield a consensus on the South China Sea.

The United States Pacific Command (PACOM) has taken an increased interest in the developments in the South China Sea, with its commander Admiral Harry Harris terming the land reclamation “China’s Great Wall of Sand”. The fear is that via these reclaimed atolls, combined with advances in ballistic missiles, China could limit freedom of movement for the US Navy’s aircraft carriers as part of an Anti-Access Anti-Denial (A2/AD) strategy.

Until recently, PACOM has avoided sending its vessels within 12 nautical miles of the artificial islands as part of the UN Convention on the Law and the Sea (UNCLOS). However, this may be about to change. Recent reports indicate that the US Navy may challenge the legitimacy of these islands by sailing within the 12 mile zone, calling into question whether reclaimed reefs and artificial structures are protected under international law.

China is not immune to the tide of international opinion. On August 5, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced that China would halt all land reclamation in the region and would work towards a Code of Conduct with South East Asian states signal that Beijing is seeking to alleviate concerns and avoid building a regional consensus against its actions.

Nonetheless, as a regional power in terms of both economy and population, Beijing is seeking to develop maritime capabilities consistent with its status. Historical narratives dating back to the Han Dynasty enable China to assert itself more forcefully in the contested South China Sea.