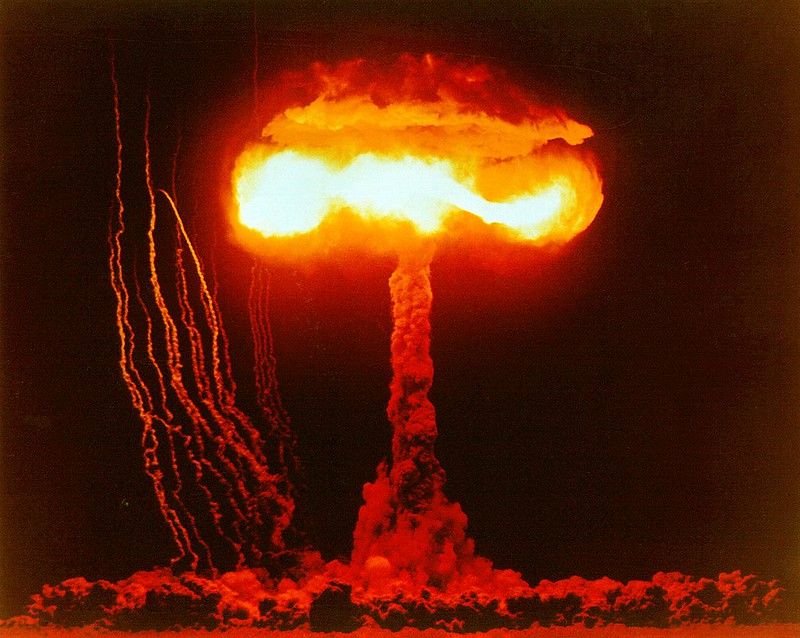

One of the most challenging scenarios emerging from Russia’s illegal seizure of Ukrainian territory centres on a potential Russian military strategy termed “escalate to de-escalate.” In this instance, Russia would detonate a small tactical nuclear device in Ukraine. Unlike ballistic missiles, tactical nuclear weapons have relatively low yields (1-50 kilotons) and are designed to destroy smaller targets such as military formations or logistics points. According to this strategy, the use of such a weapon in Ukraine, at a target of military or political significance, such as a Ukrainian military unit or Kyiv, would demonstrate Russia’s willingness to use any means necessary to keep its recently annexed territory and oveawe NATO with the prospect of a nuclear exchange. Such a scenario would unleash a nightmare policy choice for NATO: respond in kind or allow the detonation to pass without a similar display, thus legitimizing the use of nuclear weapons in warfare. Fundamentally, the use of nuclear weapons would change the calculus by which Western planners, including Canada, viewed the stakes of the conflict.

At present, NATO member states have the luxury of allowing Ukraine to fight the Russian military, while supplying arms, finances, and knowledge without risking NATO soldiers. However, the use of nuclear weapons would immediately widen the conflict to a continental or even global scale. In this scenario, there are likely several responses available to NATO, but all of them have the potential to escalate the conflict into a general war, if not an outright nuclear exchange. Note that both Ukraine and the US have noted that inaction and allowing Russia to keep the annexed Ukrainian territory by seeking a diplomatic settlement are rejected as possibilities, even before a nuclear weapon has been detonated. It is also assumed that non-military options, such as further economic sanctions, blockading ports and trade, and global financial isolation, would necessarily follow.

While there are no good options, three potential scenarios might follow a Russian nuclear detonation, depending on NATO’s perspective:

Option 1: NATO issues an ultimatum for Russia to withdraw from Ukrainian territory. There is no immediate response in kind to Russia’s nuclear provocation, but military units are staged and made ready for action if necessary. This attempts to stave off a general Russia-NATO conflict for as long as possible by allowing Russia to withdraw peacefully, and if this is unsuccessful, to maintain any future conflict as a conventional (that is, non-nuclear) one. Russia’s failure to withdraw would likely lead to the next option in this list.

Option 2: NATO decides that an immediate military response is warranted to demonstrate the Western consensus that nuclear weapons represent a dangerous red-line. While there is no corresponding nuclear detonation from the West, NATO forces sweep the skies of Russian aircraft over Ukraine, sink the Russian Black Sea Fleet, and neutralize Russian staging points, supply chains, and command posts supporting the Ukraine conflict. NATO stops short of direct attacks on Russian territory, but nevertheless directly engages Russian soldiers in combat.

Option 3: NATO decides that an identical or proportional response-in-kind is merited and uses a single tactical nuclear weapon to eliminate either a Russian target of opportunity in the Ukrainian theatre, or a similar target in Russia itself. In this instance, NATO does not stand up a defence of Ukrainian territory, nor take any further action to engage Russian forces (as in Option Two). Rather, NATO’s objective is to reinforce the idea that using nuclear weapons will always merit a nuclear response, as nuclear deterrence remains a core element of NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept. In this event, continual nuclear escalation might be difficult to stop once it begins.

In all three scenarios, the risk of a general nuclear exchange remains substantial. It is possible that Russian President Vladimir Putin believes he may be able to break NATO’s consensus by attacking some member states (i.e., the Baltic states), but not others, in order to divide the alliance by putting domestic pressure on political leaders not to intervene. Such a policy was outlined in a report from 2018. Would many Americans, for instance, trade New York City for Riga? Would many Canadians trade Toronto for Tallinn? Ukraine is not a NATO member; would the alliance risk global nuclear war for a non-member state? Former president of Russia Dmitri Medvedev stated a similar point in a recent interview: even if Russia used a nuclear weapon in Ukraine, NATO would put its own security needs first over “a dying Ukraine that no one needs.”

NATO may even find its options eclipsed by individual member states. As reported in recent statements, the US has communicated its potential response to the Kremlin, and whether or not this includes the entire NATO alliance has not been made clear. As part of NATO, Canada is also committed to upholding the alliance through political, military, and economic means. Politically, Canada has maintained NATO’s consensus to fight a potential world war since 1949, and must be prepared to endorse and support a nuclear demonstration if the situation deteriorates to such a point; to do anything less could render the alliance ineffective.

While it is possible that none of these options and scenarios will occur, the fact remains that a nuclear exchange may be at its likeliest point since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, and understanding the risks involved, by all parties, is the clearest way to avoid a situation spiraling out of control.

Photo: ‘US Nuclear Weapons Test in Nevada, 1953’, by International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (2012). Licensed by Creative Commons under CC BY-BC 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.