Amidst intensifying geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific region – marked by China’s aggressive expansion of its military presence and the escalation of territorial disputes, the absence of formal, collective security alliances has become increasingly conspicuous. Unlike the North Atlantic, where the North Atlantic Treaty has successfully deterred aggression against member states since the foundation of NATO, the Indo-Pacific remains without a centralized security architecture to generate a unified response to external threats. Instead, states within the region have increasingly turned to minilateral security arrangements, characterized by flexible and overlapping networks of small-scale coalitions of like minded countries. This contrast has raised the question of why NATO-style alliances have failed to materialize in the Indo-Pacific and how minilateral approaches can deter aggression moving forward.

The answer to these questions lies in the starkly different geopolitical contexts from which these regions emerged. The founding of NATO can be attributed to the post-WWII environment in North America and Europe where existential threat, economic reconstruction, and interstate reconciliation created the conditions necessary to formulate a centralized collective defence. The Marshall Plan set the conditions for NATO amidst a common threat from the Soviet Union’s expansion, based on a foundation of reconciliation post-WWII (e.g., the Franco-German partnership). This made collective defence politically viable for NATO states. In contrast, for Pacific nations, a different geopolitical context shaped by post-colonial identities, historical grievances, and norms of neutrality and non-alignment dating from the 1955 Bandung Conference have influenced strategic calculus. This contextual difference has challenged the viability of NATO-style collective defence in the Indo-Pacific and left a legacy that persists to the present. Instead, while no collective security treaty exists to deter aggressors, minilateral approaches have emerged to overcome barriers to greater cooperation.

During the emergence of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), weak socio-political cohesion of the region’s new states after independence, limited state capacity in many postcolonial governments, interstate territorial disputes, and various instances of intra-regional ideological polarisation took shape. The lack of a shared perspective on geopolitical threats, and intervention by external powers set the tone for the regional security environment of the early postcolonial period. Conflicts such as the Sabah dispute between the Philippines and Malaysia, the Indonesia-Malaysia-Singapore Konfrontasi, Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia, and the ASEAN-Indochina polarization posed a threat to any hope for peace in the region. These conflicts led to the “ASEAN-Way”: a set of norms including non-interference in the internal affairs of states, the rejection of an ASEAN military pact, and the preference for bilateral defence cooperation to protect regional autonomy. Given the lack of cultural and political homogeneity as an adequate basis for regionalism, collaboration had to be constructed through arrangements that promote sovereign equality between formal equals. Despite these challenges, the region has enjoyed undeniable success at preventing armed conflict, with the last major interstate war in the region having broken out in 1979.

By engaging with each other on small-scale arrangements based on specific issues, minilateralism has allowed states to overcome the barriers to multilateralism, giving states the space to cooperate without discounting their historical differences by avoiding binding alliance commitments on sensitive issues. Moreover, minilateralism lowers the domestic political costs of cooperation. This is because it avoids alliance commitments that might threaten a state’s identity, where the binding nature of multilateral defence treaties can impede states’ ability to maintain their political sovereignty or force states to give up historical grievances that they consider central to their identity. This enables sustainable security coordination even with heterogeneous and politically fragmented states.

The importance of minilateralism and loose coalitions of formal equals in the Indo-Pacific region is further illustrated by the “Quad” (i.e. United States, Japan, Australia, and India), which has – despite potential to do so – deliberately avoided becoming a formal military alliance, and rather, a favorable sovereign equality of states in the Indo-Pacific in which “no country dominates, and no country is dominated”. To the contrary, the nature of cooperation in the Quad is driven by India’s commitment to non-alignment. The Quad’s success was achieved in areas of freedom of navigation and maritime order, whilst still allowing India and the rest of its members to coordinate on shared challenges without undermining its commitment to strategic autonomy and formal non-alignment.

Similarly, the “Squad”, a trilateral agreement between Australia, Japan, and the U.S., demonstrates the region’s clear inclination towards targeted, narrow cooperation as opposed to comprehensive multilateral defence treaties. With its issue-specific focus on deterring coercion and aggression across Asia in light of China’s recent actions in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, this informal agreement includes no mutual defence obligations, nor does it attempt to unify threat perceptions across the Indo-Pacific. Its small architecture permits the alignment of four states that already possess shared security interests, creating a space to strengthen defence within the Pacific’s unique context, where larger multilateral alliances would falter. In response to shared South China Sea threats issue-specific partnerships, ranging from Japan-Indonesia cooperation on defence equipment to Japan-Philippines coordination, have emerged.

Beyond minilateral agreements, much of the region has traditionally relied on bilateral defence partnerships. A clear example is the San Francisco “Hub-and-Spokes” system, which is a backbone of the United States’ commitment to Indo-Pacific security. This patchwork of bilateral treaty alliances sets the United States as the “hub” with its Asian allies (i.e Japan, South Korea and the Philippines) as “spokes”, each with its own individual Mutual Defense Treaty. These bilateral agreements avoided the risk of pooling states into a consolidated direction amidst a shared threat. Its heterarchical system, diffusing power rather than concentrating it, has preserved each state’s control over its extent of cooperation on a case-by-case basis, preserving strategic flexibility.

Despite the benefits of increasing use of informal, purpose-driven coalitions to diversify partnerships and mitigate risks without committing to inelastic coalitions, such mechanisms share their own challenges. Their flexibility and lack of centralized enforcement can make member states vulnerable to shifts in national priorities and political turnover, a vulnerability made evident today with the increasing threats of aggression in the South China Sea. Other scholars like Fulvio Attinà have argued their exclusivity risks “further disempowering smaller, less powerful states, exacerbating power asymmetries through discrimination”. While appropriate within the postcolonial context of the Indo-Pacific region, in the long run, minilateralism is neither inherently a universal cure nor a threat. Its true efficacy is contingent upon its application, and whether it can serve as a complementary approach to strengthening a shared rules-based international order.

In this sense, Western states hoping to deepen engagement in the Indo-Pacific region ought to pursue small-scale security arrangements to generate meaningful outcomes in specific, modular areas as opposed to pursuing ambitious, region-wide ones. Successful examples such as the Quad, Squad, and the Hub and Spokes system between the U.S and its allies in the region demonstrate how minilateralism can be effective when they are flexible and sensitive to regional norms. While the Indo-Pacific region may not have emerged from the exact same political and historical foundations for collective security treaties as comprehensive as NATO, the West can still cooperate with regional partners to tackle shared challenges by endeavouring flexible, issue-based minilaterals that take into account the region’s heterogeneity.

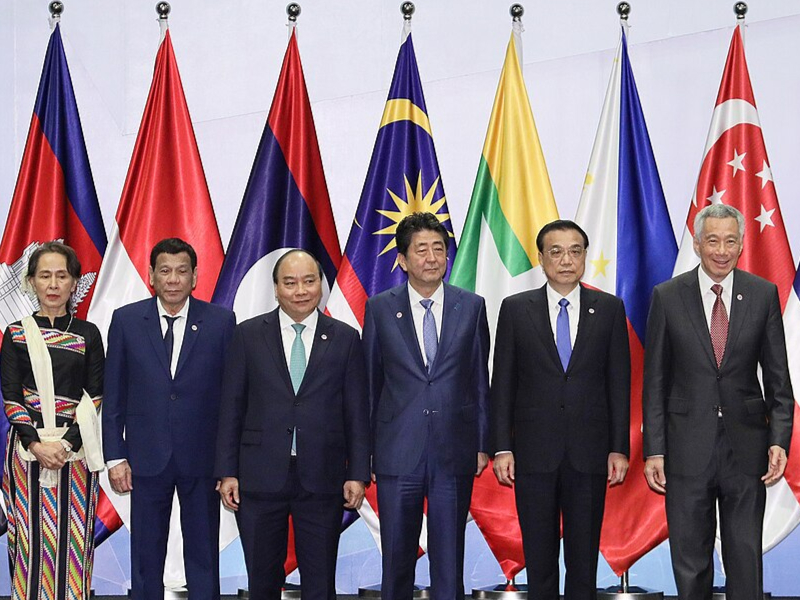

Photo ‘ASEAN + 3’ licensed under the Government of Japan Standard Terms of Use (Ver.2.0). The Terms of Use are compatible with the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. Image cropped.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.