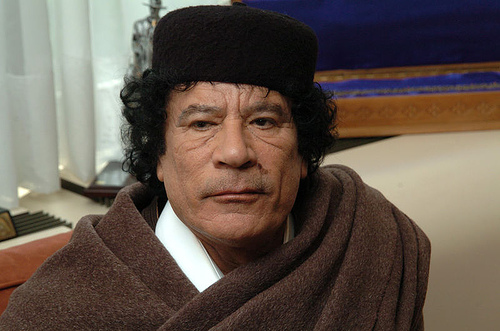

Five years ago, Libya was a stable and moderately prosperous country under the rule of the dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Though the regime was oppressive and corrupt, Gaddafi maintained relatively good living standards and kept the nation free of Islamic extremism. When Gaddafi gave up his nuclear and chemical weapons programs in 2004, sanctions on Libya were lifted and the West viewed the regime as safely predictable in a region filled with uncertainty. Thus after 2004, the world community largely ignored the humanitarian abuses of the Gaddafi regime, preferring a strong dictatorship that would crack down on potential terrorist groups to unstable governments that could serve as extremist havens.

In 2011, this strategy would be tested with the coming of the Arab Spring. Suddenly, the Libyan government was anything but stable, as the effects of years of oppression began to rear its head with mass uprisings throughout the country. In front of the lights and cameras of the world media, Gaddafi moved to crush the opposition in Benghazi and restore his iron grip on the country. To let him proceed would have been a massacre, a humanitarian crisis of the highest order. The U.S. and NATO decided that they were unwilling to stand by, intervening by launching airstrikes and Tomahawk missiles to cripple the Libyan military. With foreign assistance, the opposition deposed Gaddafi and his regime, and a new government, the democratically elected General National Congress (GNC), took power in 2012.

With the ascension of the GNC, the Western governments that toppled Gaddafi appeared to feel that the heavy lifting was over, and that the success of democratic elections was a sign Libya would be able to manage on its own. Their exit was hastened by the prevailing political climate: state-building in the Middle East was not in fashion among nations of the West, and after the difficulties NATO and the U.S. encountered in Afghanistan and Iraq, Western powers had little appetite for committing large amounts of manpower and resources to rebuild Libya after the civil war. Reconstruction efforts were thus decidedly minimal. For instance, the UN’s Support Mission to Libya had no mandate to engage in Libyan politics, and was comprised of a paltry staff of only 200 soldiers. Similarly, the EU established only a political mission to Libya, a weak effort when compared to the far more robust civilian-military mission it had deployed in Kosovo during the 1990s. Foreign involvement in Libya was further weakened after the attack on a U.S. diplomatic compound in Benghazi in September 2012, where four Americans were killed. The incident caused a political firestorm in Washington, causing the Obama administration to reduce the scope of an already miniscule diplomatic presence in Libya. Thus, with little foreign aid, the Libyans were left on their own to deal with the monumental tasks of building political institutions and establishing security in a country that had only just recovered from a bloody civil war.

As one might expect, given the immense challenges faced by its new leaders, Libya has struggled to manage its own reconstruction. Though the newly minted GNC possessed a majority of centrist and secular political parties, the Islamist forces that had been marginalized in the elections began to assert their influence by turning to violence and intimidation. In December 2013, Extremist militias, groups that had seized weapons from abandoned Gaddafi-era military armories, stormed government ministries and forced lawmakers to endorse Sharia law as the source of all legislation. In February 2014, secular military forces, including many units that served under Gaddafi responded by launching a coup and dissolving the GNC, which had itself been taken over by Islamists. These secular forces launched “Operation Dignity,” a large scale offensive against extremist militias in Benghazi and Tripoli. Only three years after the end of the civil war to depose Gaddafi, the country was plunged back into the grip of violence and chaos.

Fighting between the secular forces and a coalition of Islamist militias known as Libya Dawn raged for months, claiming thousands of lives. Eventually, a ceasefire was brokered between the two sides dividing the country into an eastern territory controlled by moderate military forces and a western territory controlled by the Libya Dawn coalition, with Benghazi and certain areas on the far western border under the de-facto rule of local tribesmen and Islamists. While the ceasefire has largely ended hostilities between the two major factions, a new threat has emerged within the past few months: the arrival of ISIS.

Throughout late 2014 and 2015, battle-hardened members of the Islamic State have taken advantage of the chaos in Libya to establish a presence in the country. ISIS forces have taken control of Gaddafi’s former home city of Sirte, along with significant portions of Libya’s “Oil Crescent,” one of the region’s most oil-rich, lucrative areas. In the past few weeks, Islamic State has continued to advance, recently beginning an offensive on the city of Misrata, the third largest population center in Libya. During their operations in Libya, ISIS forces have demonstrated the same brutal tactics of local administration they have implemented in Iraq and Syria, establishing complete control over courts, education and police forces while instilling fear through dozens of bloody executions.

However, the most concerning aspect of Islamic State’s presence in Libya to the West is its newfound potential access to Europe. Libya is approximately 200 miles from the southern shores of the European Union. With ISIS establishing a significant presence in the embattled country, it is possible that the organization will look to send fighters to the southern European countries of Italy, Greece or Spain, among others. With the mass of migrants streaming from the Middle East, many travelling on rafts and small boats across the Mediterranean, it is easy to envision ISIS militants from nearby Libya blending in with migrants to slip through EU borders. Such militants could wreak havoc in the EU, establishing sleeper cells from which to conduct terrorist attacks on transportation networks, heavily populated areas or government centers.

After the overthrow of Gaddafi, Libya was seen by many as a shining example of the best of the Arab Spring, a grassroots revolution that succeeded in toppling a brutal dictator. The rapid deterioration of this promising outcome is a tragedy that has been largely ignored by a world focused on turmoil elsewhere in the Middle East. The West was content to leave Libya to fend for itself after playing an instrumental role in tearing down a power structure that had been in place for decades. One can only hope that Libya can avoid the same fate as Iraq and Syria, once-strong dictatorships now consumed by the terror of Islamic extremism.