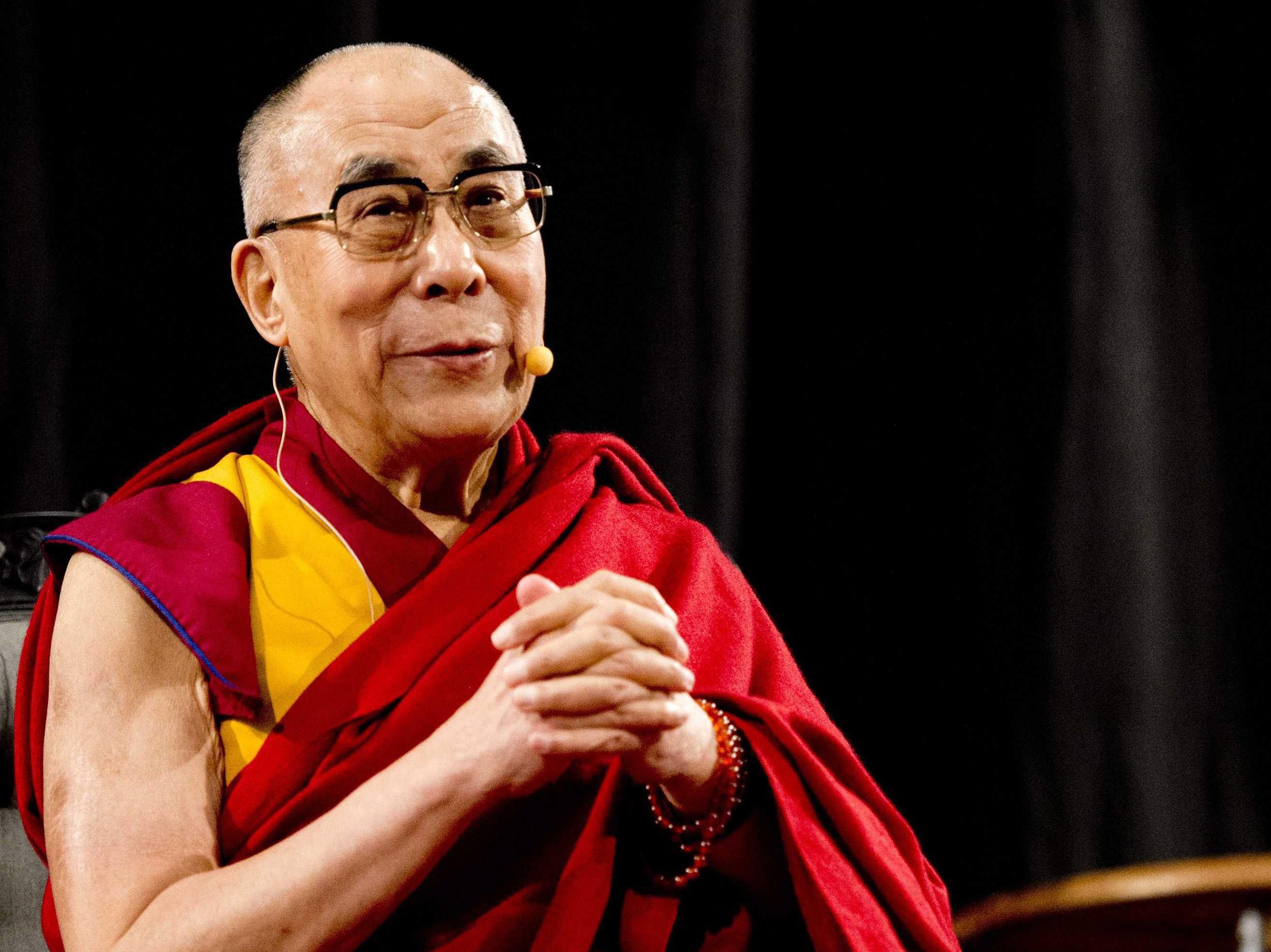

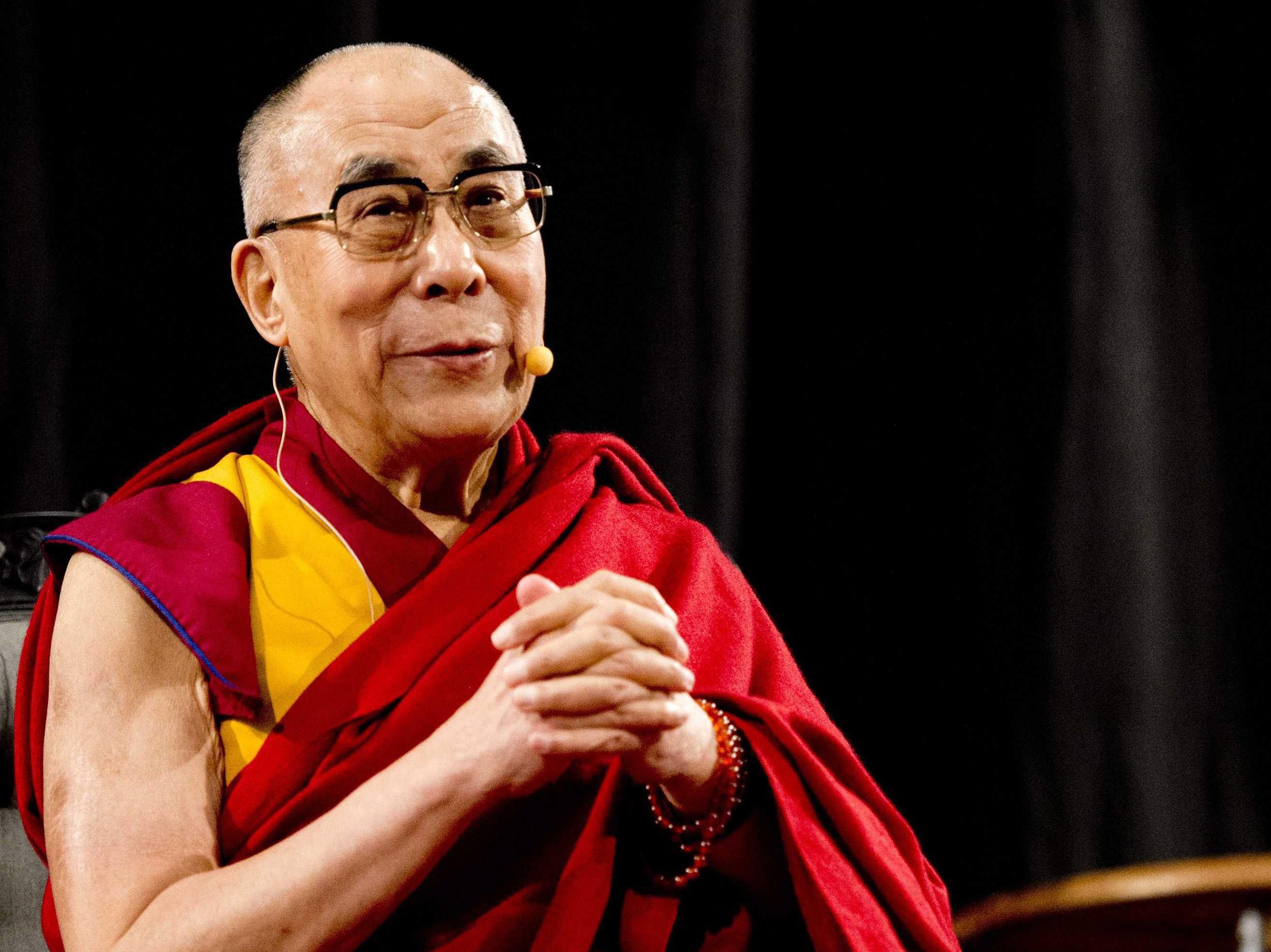

In May 1951, China began its forceful implementation on the Tibetan government of the “Seventeen-Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet”. Since then, Chinese policies have repeatedly attempted to assimilate the Tibetan population through a brutal cultural genocide. Interestingly, Tibet is internationally accepted as an independent state: the seventeen-point treaty, having been signed under duress, is void under international law. However, the exiled Tibetan government has yet to be formally acknowledged by any international power. Only the Dalai Lama can be said to have some sort of international stature, being commonly seen as a symbol of Buddhism and Tibetan culture’s survival in the face of forced Chinese assimilation. After a failed Tibetan revolt in 1959, the Dalai Lama claimed asylum in India, along with several Buddhist monks and 6 cabinet ministers of the former Tibetan government.

The Holy leader’s advancing age has led to much speculation as to what effect his death would have on Tibetan culture and Buddhist religion. The Buddhist faith holds that when a soul leaves a dying body, it is instantly reincarnated in the body of a baby born at the same exact moment. After each of the Dalai Lama’s “bodily” deaths, the first regent of the monks is tasked with the nation wide search for the “reborn” Dalai Lama. This regent is none other than the Panchen Lama, who himself is also a reincarnated Buddhist figure that the Dalai Lama is tasked with finding and rearing, imparting upon him the knowledge required to discern the true Dalai Lama from likely impostors. It is the Panchen Lama and Dalai Lama’s dual rising nature and often close relationship that has earned the religious pairs the nicknames of sun (Dalai) and moon (Panchen).

At the time of the forced implementation of the 17-point agreement, the Tibetan people were being partially lead by the 10th Panchen Lama, Choekyi Gyaltsen. Although the latter had always openly criticised China’s policies towards Tibet, he did attempt, until the failed revolution of 1959, to coexist peacefully with their government. However, after the Tibetan government’s forced exile, he formally and vigorously protested the Chinese occupation, producing a now famous 70 000 character petition. This petition landed Choekyi in jail, from which he was only released in 1978. After his incarceration, he traveled throughout Tibet, attempting to raise awareness about Chinese actions in the region and their impact on the Tibetan people. Shortly after these addresses, however, the 51-year old Panchen Lama died under “mysterious circumstances”.

“We would like to remind the Chinese government of their brutal acts of the sudden killing of the 10th Panchen Lama and thereafter having snatched and incarcerated his reincarnation recognised by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.”

On the 24th anniversary of Choekyi’s death, and the birthday of the 11th Panchen Lama, the exiled Tibetan government released a shocking statement. “We would like to remind the Chinese government”, they stated, “of their brutal acts of the sudden killing of the 10th Panchen Lama and thereafter having snatched and incarcerated his reincarnation recognised by His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.”

Indeed, in 1995, the Dalai Lama recognised a young boy, named Gendun Choekyi Nyima, as the Panchen Lama of this reincarnation cycle. However, the compound in which Gendun was staying was raided; the boy was soon claimed missing and, a while later, presumed dead. The inability to confirm the Panchen Lama’s death meant that the Dalai Lama could not start a new search for another Panchen Lama. To amend this, the Communist Party of China selected their own Panchen Lama: another young boy of the same age as Gendun, named Gyaltsen Norbu. Gyaltsen is to be brought up alongside Chinese political figures and taught the party doctrine until the time of the Dalai Lama’s death, at which point the newly communist Panchen Lama will be tasked with finding a reincarnation.

Faced with this new plan of action, the Dalai Lama responded that, after his passing, he would not be reborn within China, or even as a Chinese Citizen. The search for the next Dalai Lama would therefore become a global project outside of the China-controlled Tibet – much to China’s discontent. The 4th Dalai Lama was the only one to be born outside of Tibet so far, hailing originally from Mongolia. The idea of a global search, as daunting as it may be, is therefore not unprecedented.

The current Dalai Lama further questioned whether or not the world had grown out of its need for religious figures — and whether or not he would be reborn at all. Some were particularly unnerved by the Dalai Lama’s bold declaration that he felt he might be next reborn as a woman. Even more controversial for Buddhist followers was his suggestion that he choose his own successor, either in person or via a democratic process amongst the more influential monks. This all assumes that the Dalai Lama would be reborn as a human, and not an animal or an insect — a possibility to which he alluded in the nineties.

These foundation-shattering changes are not meant to occur any time soon. In fact, the 79-year-old Dalai Lama stated that they would only be seriously discussed once he turns 90. That being said, the Holy figure did confirm that a growing number of duties were being turned over to younger, elected officials as he himself grew older.