Acts of injustice and violence are robbing children of their childhood throughout Afghanistan. In 2017, there were 3,179 reported cases of children killed and maimed due to conflict-related violence. This rate is on the rise, with the war in Afghanistan killing a record number of civilians in 2018. A number of the children killed in the violence include child soldiers, as many of the military and governmental officials subscribe to the troubling perspective that “if you are old enough to carry a gun you are old enough to be a soldier.”

What is a Child Solider?

In order to describe the issue of child soldiers, we must begin with a clear and concise definition on what exactly a child soldier is. The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) defines child soldiers as “any child – boy or girl – under eighteen years of age, who is part of any kind of regular or irregular armed force or armed group in any capacity.” This age limit, of eighteen and younger, is relatively new. It was established in 2002 by the Optional Protocol to the Convention of the Rights of the Child. Prior to this, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the 1977 Additional Protocols set fifteen as the age limit. However, this age protocol is rarely followed in the international community – as recently reported by the Los Angeles Times, three-quarters of all world conflicts involve child soldiers.

History of Child Soldiers in Afghanistan

The use of child soldiers in Afghanistan dates back to the 1980s, when the Soviet-backed government founded the Democratic Youth Organization (DYO). The DYO’s main prerogative was to recruit children between the ages of 10 and 15 years old to act as soldiers and spies for the military. From 1979 to 1986, approximately 30,000 Afghani youth were sent to the Soviet Union for ‘educational purposes.’ A Middle Eastern report states that an estimated 1.8 million people were killed in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, of which more than 300,000 were children.

Following the Soviet Union’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, the Afghan conflict snow-balled into an all-out civil war, involving large numbers of child soldiers. The Soviet invasion drastically affected the social landscape of Afghanistan for generations. On the devastation, political scientists specializing in Afghanistan, Ralph H. Magnus and Eden Naby stated, “Truly this became a generation that sacrificed itself.” For what you might ask? That remains the million-dollar question.

The use of child soldiers in Afghanistan continued after the intervention by Western countries that followed the September 11th terrorist attacks of 2001. In 2006, Afghanistan’s government and the international community joined in an Afghanistan Compact, a framework for rebuilding Afghanistan’s social structure. In order to complete this operation, approximately 50,000 international troops remained in Afghanistan, 39,500 of those being under the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). However, a resurgence of Taliban forces challenged the set Afghanistan government and its Compact, leading to a weaker government, an increase in insurgency, and a rise in the number of civilian casualties. Involved in the conflict were countless armed militant groups, many of whom employed child soldiers. Reports of forcible and voluntary recruitment by the Taliban of children in the southern provinces of Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan flooded the international and Afghan communities. In July of 2007, it was reported that a 14-year-old boy from Pakistan was held in custody wearing an explosive vest to target the governor of Khost province. He professed to having been captured by Taliban forces and coerced at gunpoint to attack the governor of Khost. The direct impact of war on children remains evident throughout the country, with disabled and maimed children constituting a majority of street beggars and child labourers. It is estimated that more than four million children have acquired disabilities due to war. These children are often left hopeless and in dire states.

Since 2007, the conflict is Afghanistan has continued on. By the end of 2014, Afghan elections brought in a national unity government and, as a result of the perceived stability, NATO ended its combat mission. The Afghan National Security Forces (ANFS) took responsibility for Afghanistan’s rather fragile security. Despite efforts put forth by the ANFS, the conflict has continued to rise. As a result, the armed militias continue to operate in many parts of Afghanistan, many of whom use children in some way. Patricia Gossman, a senior Afghanistan researcher, declared that the “Taliban’s strategy to throw increasing numbers of children into battle is as cynical and cruel as it is unlawful…Afghan children should be at school and at home with their parents, not exploited as cannon fodder for the Taliban insurgency.” The recruitment of child soldiers remains a prominent factor in the conflict in Afghanistan.

Child Soldier Recruitment Worldwide

Military forces and personnel target children to be trained as soldiers for a variety of reasons. Firstly, in terms of psychology, children are easy to manipulate, scare, and torment into committing acts of grave violence. Many children are seduced by armed forces into joining the military, with tales of adventure and glamourized violence circling Afghan communities. Moreover, many children in Afghanistan are orphans and, in turn, are lacking economic opportunities. Some are motivated by the payment incentives provided by the military and, in turn, voluntarily join the military. However, the fact remains that many children are kidnapped and forced at gunpoint into taking up arms.

Afghanistan is not the only country practicing the recruitment of child soldiers; rather, it is a worldwide atrocity and, in turn, a worldwide responsibility. Around the globe, more than 240 million children are living in countries that are deeply affected by widespread violence and conflict. As a result of the violence, many of the children are facing violence, displacement, hunger, and exploitation. In 2000, the United Nations (UN) issued a report stating that 36 countries were currently involved in conflict in which child soldiers were taking part. When coalition forces entered Iraq in 1991 and 2003, they were confronted with resistance by Saddam Hussein’s ‘lion cubs.’ These were children from an after-school club promoted by the dictator, where military training and absolute political indoctrination took place. In 2011, the former Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was accused of using child soldiers to conduct a siege of rebel forces. The Child Soldiers World Index, developed by humanitarian organization Child Soldiers International, reported that more than 20% of the 197 UN Member States still enlist children into their militaries. Children are being deprived of their childhoods around the globe. Not only is the use of child soldiers wrong on a fundamental level, it is also deeply unlawful.

Has the International Community Helped?

The recruitment of child soldiers is understood globally to be a violation of international law. Many international laws and conventions have been put in place to help combat and, ultimately, to put an end to the recruitment of child soldiers. The use of children in combat zones goes against International Humanitarian Law (IHL) which states that any child under the age of 18 shall not be recruited into armed forces operations or non-state militant groups. The document outlines that under no circumstances should a child take part in any hostilities. Furthermore, the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court (ICC), of which Afghanistan is a member, deemed that using children under the age of 15 in combat is a war crime. As has become ever more prevalent, these conventions are not being followed. In 2003, Afghanistan ratified the Optional Protocol on the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, stating that people under the age of 18 cannot be recruited. In May of 1998, leading non-governmental organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, formed the Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers.

In terms of international organizations, the United Nations (UN) Security Council adopted resolutions 1539, in 2004, and 1612, in 2005. Both the resolutions call for the establishment of mechanisms to monitor children in armed conflict. The mechanisms are now set up in countless countries around the globe. The fact remains that the implementations put in place by the international community, although they have helped somewhat, have not been truly effective. Children around the world are still vulnerable, as countless governments continue to recruit people under the age of 18, exposing them to abuse, hazardous activity, and, in many cases, actual deployment into war-torn zones.

At the Chicago Summit in 2012, NATO leaders first addressed the need for protection of children in armed conflict. NATO understands protecting children in armed conflict as a moral imperative and an essential component of global security and, as a result, is taking strides to confront this global issue. In close partnership with the UN, NATO developed Protection of Children in Armed Conflict– the Way Forward. The policy provides clear support to integrate the UN Resolution 1612, which condemns the use of child soldiers worldwide. Furthermore, NATO has a Senior Focal Point for Children and Armed Conflict. Throughout NATO’s mission in Afghanistan, NATO adopted the Resolute Support Mission, which actively supports the international community’s effort to protect vulnerable children. In 2013, NATO produced an electronic-learning module on the topic of protecting children. The module is available to all Allies, as well as all allied partner countries. It provides an outline of the six violations against children identified by the UN Secretary-General, along with the relevant framework needed for the protection of children in war-torn zones.

Since the establishment of the UN’s Action Plan concerning the recruitment of child soldiers, over 130,000 children have been released from military captivity. The fact remains that children in conflict-zones will always be at risk of danger. However, it is possible to reduce the risk of children being recruited as soldiers. International organizations, including the UN and Child Soldiers International, both recognize the logical first step to be establishing 18 as the minimum required age for recruitment. The majority of states have adopted this, but many non-state armed militias have not. Setting limits on the age of recruitment is not the only solution needed – total societal development plays a crucial role as well. This includes, but is not limited to, promoting education and employment. Educational institutions can actually get caught up in the conflict between the government and non-state rebel groups, and can even be used as institutions of propaganda and recruitment for the children. Exposure to war and conflict has drastic effects on children, as they deprive children of having a normal and healthy childhood, as well as hindering their full integration into society as functioning members. There is also a danger of ‘re-recruitment,’ referring to when a child is unable, due primarily to psychological problems, to integrate back into their society following their time as a child soldier. As a result, they are pushed back, or coaxed back, into the war effort. Child soldiers have to cope with continues effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), due to exposure to conflict, acts of abuse, violent death of a friend or family member, and countless other factors. Therefore, extensive mental health services are needed, as they are essential in the rehabilitation and demobilization process. The recruitment of child soldiers is a global atrocity and, in turn, a global responsibility.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.

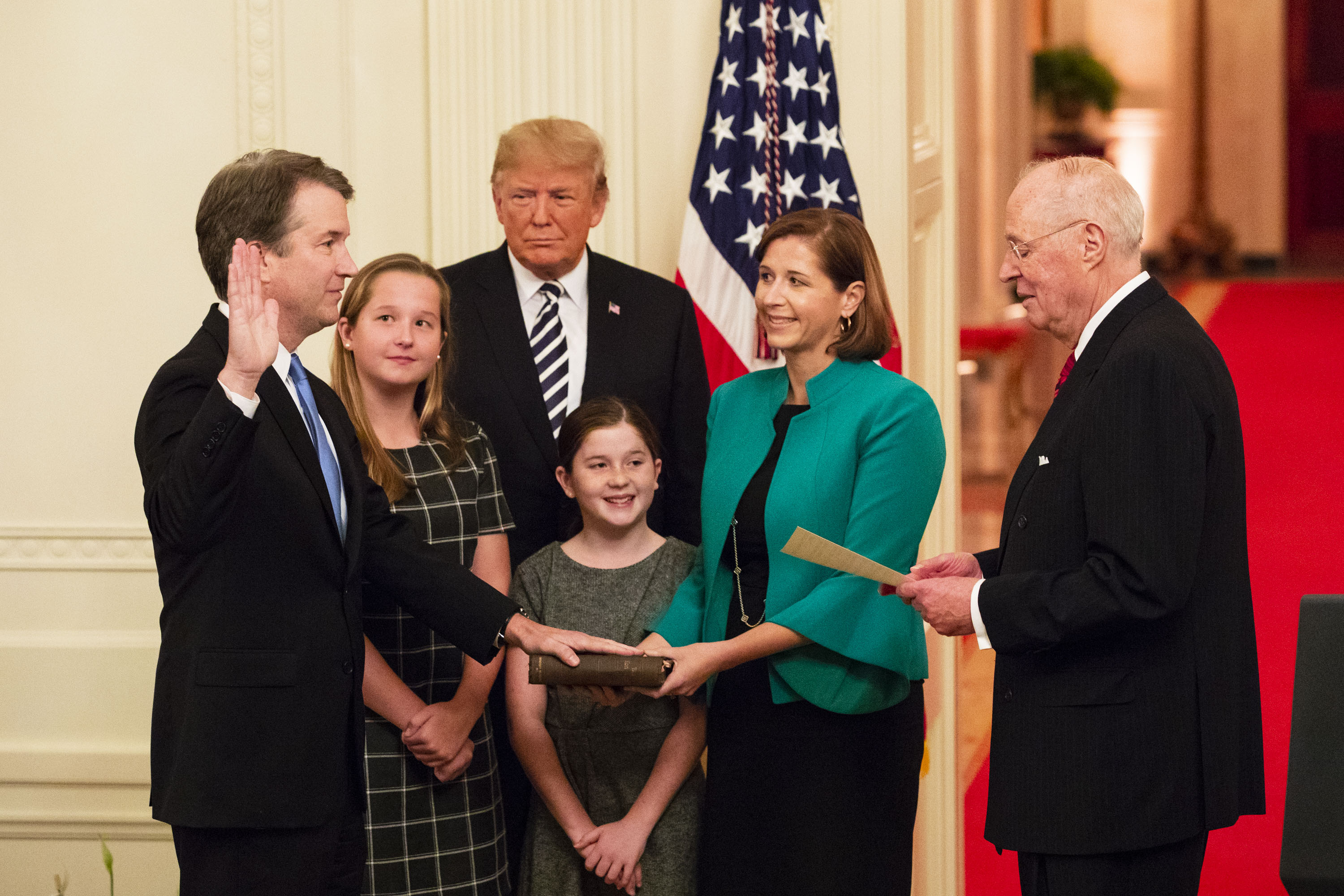

Featured Image: Afghanistan Children. via Needpix. Public Domain.

-

Emma Tallon is currently entering into her fourth year at the University of Toronto, St. George, with a degree majoring Political Science and minoring in History and English Literature. She is passionate about bringing awareness to humanitarian and environmental issues in order to incite debate and discussion on how to resolve the issues. She is the incoming Vice-President of Amnesty International’s chapter at the University of Toronto for the 2019-2020 academic year.

View all posts