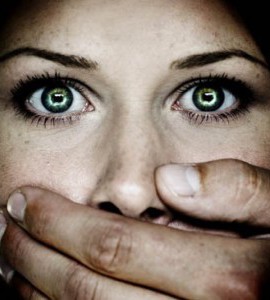

War has always impacted men and women in different ways, but never more so than in contemporary conflicts involving asymmetric warfare. While women remain a minority of combatants and perpetrators of war, they are uniquely and disproportionately affected by armed conflict. In war-torn societies, women are often confronted with specific, demoralizing forms of sexual violence and constitute the vast majority of civilian casualties resulting from war.

With support from the international community in 2000, the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325). It calls on all parties in situations of armed conflict to take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence, particularly rape and other forms of sexual abuse. While UNSCR 1325 is recognized as an unprecedented document, many resolutions, treaties, conventions, and reports have preceded it, and together these initiatives form a foundation for an international women, peace and security policy framework.

Although the Security Council annually reaffirms its commitment to the spirit of the resolution and highlights progress made in the area of women, peace and security, major gaps in implementation and accountability remain. The Security Council, despite more than a decade of calls from global civil society, has itself not yet instituted a mechanism of accountability to further the implementation of the founding resolution.

With every major conflict, the international community says ‘never again’ to widespread sexual violence and mass rape. Yet in Syria, there is a human rights crisis spanning across generations as countless women are again finding a war waged against their bodies. We continue to stand by and, though cognitively capable, remain actively impotent. As Lauren Wolfe, Director of the Women Under Siege Project, explains, “We said after the Holocaust we’d never forget; we said it after Darfur. We probably said it after the mass rapes of Bosnia and Rwanda,but maybe that was more of a ‘we shouldn’t forget,’ since there was so much global guilt that we just sort of sat back and let similar tragedies occur since and only came to the realization later — we forgot.”Could we have forgotten the unfolding human tragedy in Syria before it’s even over?

Difficulty Documenting Sexualized Violence in Syria

It is exceptionally difficult to document crimes of sexual violence in the Syrian conflict. Due to stigmatization and the role of social, religious and cultural demands, sexual assault survivors in Syria and refugees in neighboring states are reluctant to talk about their experiences. Particularly in rural and southern areas of Syria, norms forbid women and girls from talking freely about intimate and private issues such as sexual violence and other forms of violence against women. The fear and dishonor that rape brings to women and their families is so significant that many families marry off their daughters to their attackers to “protect” them from rape. Others revert to early marriage if their daughters have been sexually assaulted to safeguard the family honor. Victims feel ashamed and traumatized resulting in an unwillingness to report such crimes, rendering it extremely difficult to document their scope.

Many of the acts of violence against women that have been reported are often indirect accounts of an incident that happened to someone else – a relative, neighbor, or friend. According to an assessment on the ability of humanitarian organizations to collect direct testimonies of sexual assault provided by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic in March 2013, “Direct accounts of sexual violence continue to be sought from victims and eyewitnesses. It remains immensely difficult to collect first-hand accounts due to a culture of silence which prevents reporting.”

Women and girls are at an even greater risk of being violated in conflict-affected areas due to forced displacement, family separation, lack of basic structural and social protections, limited availability and safe access to services, and the proliferation of armed groups operating under uncertain command structures. The heightened risk of sexualized violence during the Syrian conflict, combined with the unwillingness of victims to come forward with their experiences, has resulted in the exacerbation of war crimes and rape as well as an underrepresentation of the scope of violations since the conflict began.

Sexualized Violence in Syria: The Stats

War Crimes: Since the beginning of the Syrian crisis in March 2011, the human rights situation has relentlessly deteriorated. The conflict has become increasingly sectarian and the conduct of government forces and armed opposition groups has become drastically more militarized and radicalized. Arbitrary arrests and detentions, extra-judicial executions, enforced disappearances, indiscriminate attacks on civilian areas, and the use of torture by Syrian Authorities and pro-government militias have been extensively documented. According to Human Rights Watch, the Assad government has created an “archepalego of torture centres” where detainees have been brutally tortured and denied due process safeguards. In addition, intense military operations in Homs and Dara’a, accompanied by grave human rights violations, are responsible for the internal displacement of 2 million people and more than 600,000 refugees in neighboring countries (although the true number is likely higher since many refugees often neglect registration).

Rape: Rape has been a significant and disturbing component of the Syrian civil war. Most allegations of sexual violence and rape reported has been perpetrated by government forces and the state-sponsored armed group Shabiha, during house searches, while being detained, or while stopped at checkpoints. The International Rescue Committee in Syria was told of attacks in which women and young girls were kidnapped, raped, tortured and killed in public, or in some cases, in front of family. Government perpetrators have allegedly committed the majority of the attacks the Women Under Siege Project has been able to track: 60 percent of the attacks against men and women are reportedly by government forces, with another 17 percent carried out by government and Shabiha forces together. Syrian refugees have cited rape, and the fear of rape, as the primary reason for fleeing the country.

[captionpix align=”right” theme=”elegant” width=”425″ imgsrc=”http://wmc.3cdn.net/955c4c2e3845df168e_eym6bxs6g.jpg” captiontext=”From the Women Under Siege project: http://www.womenundersiegeproject.org/blog/entry/syria-has-a-massive-rape-crisis”]

Recommendation

Although United Nations agencies and other non-government organizations are expanding their interventions to prevent gender-based violence, assistance levels are woefully insufficient to address the current needs for protection and prevention of such crimes. The international community, civil society, and governments must allocate greater resources and funding to prevent sexualized violence and ensure secure and confidential assistance to Syrian victims.

Since the initial Syria Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan launched in December 2012 by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the crisis has further intensified as civilians across the country are bearing the brunt of the on-going violence.

With violence constantly on the rise and access to security worsening, it is worrisome that only 34 percent of the requested funding requirement has been received by the United Nations and other agencies officially accredited in Syria. The ability of agencies to respond effectively and cover the protection and assistance needs of Syrians in the region will be contingent on suitable levels of funding, and the commitment of donors to share the cost of welfare and security of those most impacted by the conflict.

Increased funding must also be methodically coupled with increased efforts to ensure humanitarian access and response to the rights of those in need, especially women and girls. This includes the prioritization of community-based initiatives that help establish safe spaces for women and girls, create support networks, and improve their access to information and quality services like medical care, emotional support, economic enablement and legal aid. These safe spaces can also, according to the Global Protection Cluster, “offer a variety of services such as recreational activities for women and girls…and provide psychosocial support, sessions on reproductive health, literacy and livelihood training.” Moreover, consultation and commitments with religious leaders should be encouraged to help prevent early marriages, intra-family violence, and assist in the circulation of violence prevention measures to rural areas. Appropriate levels of funding and resource allocation would facilitate the development of safe, non-stigmatizing prevention and response programs as well as service providers trained in case management.

Lastly, to further assist access to prevention and response programs, UNSCR 1325 must be adhered to by all parties to the conflict. It serves as a tool that captures and promotes a holistic understanding of women’s rights to security. Above all, the resolution gives women the right to participate in political decisions related to security at all levels. Although more and more organizations are finding ways to use the resolution as an instrument for change, the United Nations Security Council must institute a mechanism of accountability to further the implementation and commitments of UNSCR 1325 and its surrounding framework.