The next issue from the Stavanger Parliamentary Assembly that this series will review is climate change and Arctic responsibility. The draft report focuses on outlining many of the challenges that result from climate change. While typically this falls into environmental concerns, this report seeks to look at the broader issues of energy resources, shipping, fishing, tourism, and search and rescue challenges. The report states, “As temperatures increase and ice and snow melt, the Arctic has received increased political attention as a potentially strategic region. This is largely a result of the opportunities and challenges presenting themselves.”

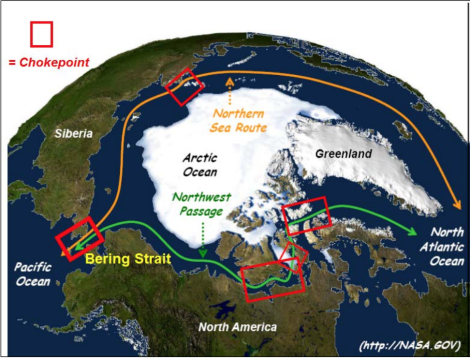

Since 2012, the Arctic Ocean had 45% less ice, and the volume of that ice was 30% of the mean it was in the 30 years prior. The impassable ice, multi-year ice, has lost 75% of its volume when compared to average. These are drastic changes, and offer a host of potentially negative consequences, but also a few opportunities. The report suggest that current developments are likely “to prompt significant investment in the Arctic states, in particular their northernmost regions. The region is, in general, conducive to economic development.” However, future developments could lead to complications as Arctic states conflict with their ambitions and values.

Arctic policy importance has gained traction in recent years as once impassable or unreachable zones of the North become accessible to the Arctic states. The report argues that, “even though five Allies are Arctic states, NATO as an organization does not have a specific Arctic policy, as Allies differ on the degree to which the Arctic should feature on their common agenda.” While sceptics of creating a unified NATO Arctic strategy cite the potential for militarization of the North, the overarching benefits may help to achieve many of the goals set out by the Wales Summit in 2014. The primary goal of which is collective defence, “as NATO is a collective security alliance guaranteeing the territorial integrity of its member states, the Arctic territories of the Allied member states falls squarely within NATO’s mandate.” Therefore, this issue will continue to be important as we move forward with the most recent declarations.

What is the next move then for NATO Arctic policy? Depending on the level of commitment and ambition, the new role could develop in a number of ways. The report suggests several different options, beginning on the low intensity scale of increasing its basic understanding of the Arctic Allied territories as existing within its domain. This would be bolstered by increased consultation and situational awareness about the changing role of the Arctic in an international context. In addition, slightly larger commitment could be invested to running, “joint small- or large-scale training and exercises with generic or more specific scenarios in mind.” Lastly, the most beneficial and assertive move according to the report, would be an increased military presence in the Arctic. All of these options are designed to better prepare NATO for an increasing importance that the international community will place on Arctic issues.

In particular, Canada has a vested interested in ensuring the relevance of Arctic issues within NATO. As one of the Arctic states, and one that currently, is severely under equipped to deal with the a potential Arctic conflict, Canada needs to ensure that Arctic policy is firmly within the sight of the Alliance. The Parliamentary Assembly will be an excellent opportunity for Canada and the other Arctic states to press the importance of this issue on their allies, and ensure that NATO is prepared for the coming ‘ice-race.’

With a substantive and focused NATO presence in the Arctic, “The Alliance could support Allies’ civilian operations, act as a forum for Arctic co-operation and communication, and serve as a framework for ad hoc responses to a wide range of activities, including disaster response or SAR operations.” This would not only benefit the Arctic states, but Alliance cohesion as a whole. It could potentially circumvent future conflicts with Russia and other parties interested in Arctic resources.

Click here to read the previous part in this series.