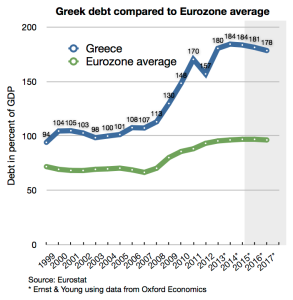

Despite strong opposition from citizens, the Greek government has conceded to its creditors and passed the required set of strict austerity measures in order to receive a bailout package of up to US $95 billion. The precise contents of the deal are still to be negotiated, but it will include targets for a primary surplus, meaning the government must take in more in tax revenue than it spends.

The International Monetary Fund and Greece’s other creditors have long argued that the country’s debt crisis could be largely resolved if the government just cracked down on tax evasion. Tax evasion and fraud have been rampant in Greece for many decades, and the government’s previous attempts to crack down on offenders have largely failed. The Greeks’ innate resistance to taxation today involves their mistrust of the government and the way it has handled the financial crisis, yet the pattern of resistance can be traced back to the time under Ottoman rule.

An investigation by the health ministry found nearly one in six disability allowances in Greece to be fraudulent, prompting the labour ministry to stop benefits to 200,000 people who either lied to get their cheques or were long since dead. The Island of Zakynthos, nicknamed the “Island of the Blind”, has become a symbol for the widespread corruption that has played a part in the nation’s financial downfall. In one of the most blatant and shocking schemes as many as 700 people, about 1.8% of the island’s population, falsely claimed that they were blind in order to receive disability benefits of approximately 350 euros a month. The scheme, which operated for years, was finally shut down in 2011 after one of the “blind” was said to have been caught driving his Porsche. In fact, an astonishing 498 of those were not blind at all, or even partially sighted. None of the those caught did any jail time for the fraudulent scheme, but instead were ordered to repay their ill-gotten gains in instalments. The scandal on Zakynthos, which the mayor estimates cost the island 2 million euros a year for the last decade, represents just a fraction of the abuses across Greece.

Economists have long studied countries like Greece that suffer from an affliction known as as “low tax morale”. This economic theory has attempted to explain why the motivation or obligation people feel to pay taxes, even exists at all. Many assumed it was a simple matter of weighing the benefit of monetary gain versus the risk of conviction. However, evidence showed that in spite of relatively low chance of getting caught, people were far more likely to pay their taxes than the numbers would suggest. Instead, a significant component in determining tax morale has been people’s satisfaction with government. As tax rates in Greece are broadly in line with those elsewhere in Europe, it is the country’s history of corrupt rulers which has fuelled the climate of mistrust and created pervasive opposition to giving money over to the state.

During Greece’s centuries long occupation under The Ottoman Empire, from the mid 15th century until the Greek War of Independence in 1821, avoiding taxes was a tool of resistance and a sign of patriotism. The Greeks even call an unpopular property tax imposed during the austerity measures the “haratsi”, a word which came from the Ottoman period meaning the ruler has the right to tax anyone for any reason with out the establishment of the rule of law. The more recent occupiers were the Nazis during World War II, hence the popularity of graffiti and cartoons depicting Angela Merkel with a Hitler moustache. While Berlin has provided the bulk of the bailout money that has kept the Greek economy afloat, Greece’s government believes their debt should be forgiven in lieu of unpaid war reparations. Greek politicians today, whether it is accurate or historically appropriate, present the austerity measures as a form of economic occupation by German overlords.

That distrust is now focused on the current government, which many Greeks see as corrupt, inefficient and unreliable. Tax evasion is once again being used as a way to exert small time resistance to the bailout agreement and strict austerity measures, which the majority of the population voted against in the recent referendum. In a report from Transparency International, sixty percent of Greeks said they expect public officials to abuse their position for financial gain and “when people believe that their leaders and officials exploit their authority with impunity, they are more likely to act along similar lines in their own lives.” The current political institutions have only existed since 1974, when the military dictatorship that previously ruled Greece collapsed, and it will take much more time for the people to develop trust in their government.

At this point in Greece’s financial crisis, tax evasion is not merely political, but economic, as the depression has already pushed the country to the brink of collapse. The younger generation, which has been hit the hardest by the austerity measures, views the previous generations and corrupt governments as the architects and owners of the debt. With Greece’s GDP still shrinking, it is almost certain that the country will default on its loans and no amount of tax increases or government spending cuts will alleviate the problem.

At this point in Greece’s financial crisis, tax evasion is not merely political, but economic, as the depression has already pushed the country to the brink of collapse. The younger generation, which has been hit the hardest by the austerity measures, views the previous generations and corrupt governments as the architects and owners of the debt. With Greece’s GDP still shrinking, it is almost certain that the country will default on its loans and no amount of tax increases or government spending cuts will alleviate the problem.