There seems to be a perception of an uneasy stability in the South Caucasus. Attention that was once focused upon that region of independence movements, skirmishes, wars and de facto states has been diverted to more pressing geopolitical matters. The delicate balance of power is deemed acceptable so long as a tense peace hovers over the complicated borders and political agreements. Nevertheless, the superficial nature of Transcaucasian security emerged yet again. Recent events in the region illustrate that South Caucasian politics remain dynamic, unpredictable and cannot be overlooked.

The scope of current insecurities in the South Caucasus covers not only wide geographical territory, but are extremely complex as well. In May 2014, while Ukraine was the centre of international attention due to the Revolution of Dignity and the annexation of Crimea, political unrest forced the overthrow of President Alexander Ankvab in nearby Sukhumi, Abkhazia. Two years later, in April 2016, the frozen Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan heated up again. Just days later, on April 11, the de facto state of South Ossetia stated its intentions to hold a referendum by late summer, seeking changes to its constitution in order to make annexation by Russia possible.

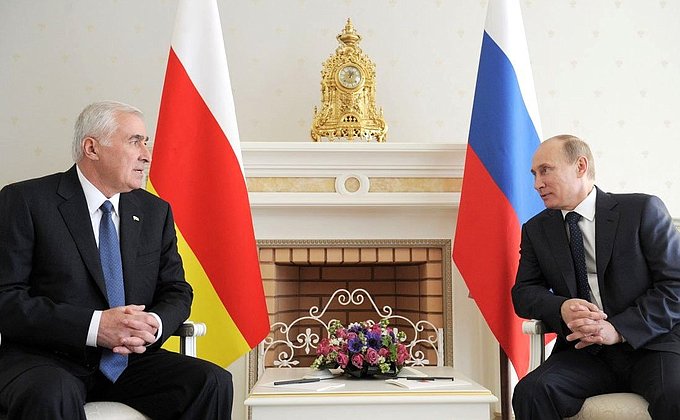

Specifically, President Leonid Tibilov confirmed that the South Ossetians hoped to amend Article 10 of their constitution. Article 10 bestows on the leadership of the small partially recognized republic, the power to enter into alliances with other states, and relinquish part of their powers to a partner. The constitutional alteration at the root of the referendum plans to denote the Russian Federation as the sole power with whom South Ossetia can form a union with the desire of integration in the future. Referendums of this nature are nothing new in the tiny de facto state, however, Transcaucasia’s re-emergence as a political hotspot and concerns of Russian revanchist behavior make this development intriguing. As this action has the capacity to dramatically shift the balance of power in the South Caucasus, the results of these actions must be considered.

Russian and South Ossetian cooperation is plentiful. The economy of the de facto state is dependent upon Russian investment and funding. Furthermore, a recent agreement between Tskhinvali and Moscow permits South Ossetia to retain its army , while other units will be integrated into the Russian Armed Forces. Russia has numerous military installations in the breakaway republic so such an arrangement is practical. As well, Russia has promoted steps that cement the small territory’s independence. The parliament of South Ossetia ratified the Treaty on the State Border with Russia which demarcates state boundaries between the two nations, instead of it as a part of Georgia. One is led to consider the motivations behind Russia’s actions. Is the regional power preparing the small republic for annexation, or is Russia simply making its South Caucasian neighbour viable as a friendly independent neighbour?

Russia is generally disinterested in absorbing South Ossetia for numerous logical reasons. The annexation of the breakaway republic means Russia would willingly adopt all of South Ossetia’s challenges. While Russia is already deeply invested, it is still a separate entity from the de facto state and not legally responsible for its domestic politics. Secondly, any move to permanently include South Ossetia into Russian territory would rupture the delicate balance of power regionally, and increase international tensions. Relations between Georgia and Russia remain unsteady, and provocations over South Ossetian territory continue. It would be unwise for the Russians to destabilize the uneasy Transcaucasian peace, especially when frozen conflicts provide them with bargaining chips in relations with their neighbours. Unlike the Russian history associated with Crimea, or the tourism and real estate ventures in Abkhazia, South Ossetia is an underdeveloped war-torn trophy. Annexation may not be worth the hassle right now.

Nevertheless, South Ossetia’s position is understandable as well. There is no doubt it is a difficult existence as an unrecognized state whose status prevents it from forging diplomatic relations and economic ties. Ossetians are a unique ethnic group that consider their unification with their brethren in the Russian federal subject of North Ossetia-Alania a sustainable solution to their struggling perception of statehood. They would greatly benefit from Russian investments in infrastructure, even though Russia may not be in a position to make such financial contributions. It is fair to assume that the territory’s reintegration with Georgia is a far-fetched endeavour. Bitter histories of conflict and nationalism prevent South Ossetians from submitting to Georgian authority anytime soon. The ongoing Russian political, economic and military influence in the territory, reinforce the notion that the conflict will remain frozen until plans for South Ossetia’s future come to fruition.

At this current time, Russia is ill-prepared to annex another territory. The South Ossetian question requires a solution, but incorporating it into Russia at this time is not a viable option. Changes in the South Ossetian constitution do not necessarily mean that the de facto state will become a Russian federal republic soon, or that Russia will exhibit undisciplined imperialist behaviors. The upcoming referendum and subsequent constitutional changes simply lay the groundwork for when it makes strategic sense to pursue a reunification of Ossetian territories in the South Caucasus. It is yet another example of why the balance of power in Transcaucasia is delicate and requires dedicated attention. Anyone with a concern for European security should keep a focus on the South Caucasus.

Photo credit to Kremlin.ru

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.