The development of a northern port for Canada in Churchill, Manitoba has involved a long and complicated drama, and its future role in Arctic trade is in doubt following a transition in responsibility for the marketing of the existing port facilities. The American firm OmniTRAX privately operates the Port of Churchill and its subsidiary, Hudson Bay Railway, has connected the port to the Canadian National Railway system, but responsibility for the further development and promotion of the port falls to the Churchill Gateway Development Corporation, originally a federal-provincial partnership that was eventually taken over by the Government of Manitoba. Apparently the provincial authorities so neglected the port that Lloyd Axworthy, who served as Canada’s Foreign Minister in 1996-2000, but who has since headed the Churchill Gateway initiative, resigned his position in January 2015 out of frustration.

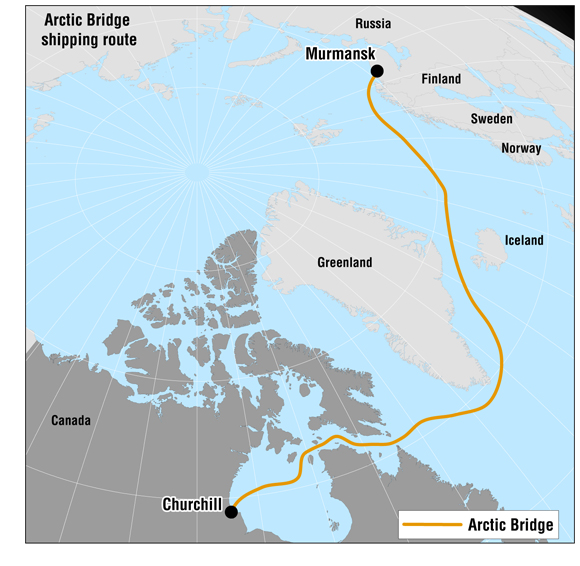

With a provincial election set for April 2016, it is uncertain whether the Government of Manitoba can be expected to step up its involvement with Churchill in the future. It may be surprising to hear, but the port’s fate may depend on something as seemingly remote as the political situation in eastern Ukraine and the future of Canada-Russia relations. This is because Churchill was originally proposed in the years following the end of the Cold War as a hub for the ‘Arctic Bridge’. This envisioned grain produced in Canada’s Prairie Provinces travelling by rail to Churchill from where it would be shipped along the southern coast of Greenland to Murmansk. From Murmansk, which remains relatively ice free, the grain would travel by rail to Saint Petersburg and the rest of Europe.

In September 2007, Churchill handled its first domestic export trade, shipping 12,500 tonnes of wheat to Halifax aboard the bulk carrier Kathryn Spirit. The next month, the port received its first international import trade, which was a shipment of fertilizer from Murmansk purchased by Farmers of North America. Since then, Churchill has played an important role in facilitating the transport of grain from Western Canadian farms to Eastern Canadian consumers, sparing both farmers and consumers from increased rail-freight costs while also avoiding Saint Lawrence Seaway charges, although the private sale of the Canadian Wheat Board leaves some question as to whether this role will continue in future years. But, for all this, Churchill never became the link with Russia many supposed it would be.

The imposition of sanctions in response to Russian aggression in Ukraine has put a freeze on any plans to remedy that neglected international role. Unless action is taken by the Canadian or Manitoban governments, OmniTRAX may soon find Churchill to have been a bad investment and withdraw. One role worth considering during such a downturn in economic activity is to add a military component to the port. With four deep-sea berths and good approaches, Churchill could accommodate vessels far larger than the Iroquois-class destroyer, the largest class of vessel currently operated by the Royal Canadian Navy. There is some question as to how tight a squeeze the approaches would be for CCGS John G. Diefenbaker, the heavy icebreaker intended for the Canadian Coast Guard by 2022. But were Churchill able to serve as a station for CCGS John G. Diefenbaker, the efficiency of icebreaking in Hudson Bay would be greatly improved.

With some uncertainty now as to whether the Government of Canada’s pre-election announcement of funding for a port facility in Iqaluit will in fact involve a full-fledged deepwater port or a small craft harbour more reminiscent of that proposed for the Nunavummiut community of Pond Inlet, Churchill becomes all the more important over the long-term to Canada’s economic prosperity. Keeping OmniTRAX engaged should be a priority for the next Canadian and Manitoban governments.