[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=” http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2011/3/17/1300357647223/Saudi-troops-Bahrain-007.jpg” captiontext=”Over 1000 Saudi troops were deployed to quell protests in neighbouring Bahrain last year”]

The Arab Spring poses both a threat and an opportunity for the oil rich monarchy in Saudi Arabia. The threat is relatively clear: as the revolution gained momentum in Tunisia in the winter of 2010 and spread to neighbouring countries, it became an existential challenge to autocratic regimes throughout the region. Several long-time rulers have fallen in both violent and non-violent uprisings, as seen in the cases of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. What opportunity does this crisis hold for the House of Saud? Is it a chance to increase its influence throughout the Middle East—a long time goal of the Saudi government?

Counterrevolution

Saudi Arabia’s response to the wave of revolutions that hit the region was clear and calculated—launch a “counterrevolution”—with the goal of containing the Arab Spring both at home and throughout the Arab world. With Saudi Arabia in the driver’s seat, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) took the lead from the Arab League as the powerhouse of inter-Arab politics (Lynch, 2011). Although evidence of the Saudi-led counterrevolution was found in many places, Lynch argues that too much credit was given to the Saudis and their attempts to shape regional politics have not been particularly impressive. Despite its less than stellar outcome, Saudi Arabia remains determined to protect Arab monarchies in the Gulf, Jordan and Morocco from the instability that is currently characterizing the region.

For now, Riyadh remains stable, largely owing to two key factors: oil and religion. However, the two forces that are keeping Saudi Arabia stable could one day be the cause of its demise. The problem begins in Qatif, a province in eastern Saudi Arabia that is home to 95% of the nation’s Shi’ite minority as well as 90% of its oil. In recent months, protests have been increasing against the systematic discrimination and human rights abuses Shi’ites face in the country. Wahhabism—the official religion of the kingdom—is ideologically anti-Shi’ite and categorizes Shi’ites as non-believers. The proximity of the protests to Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure—much of which is relatively exposed and vulnerable to attack—is a serious cause for concern for the Saudi government and those dependent on its oil exports.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=”http://media.economist.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/290-width/images/print-edition/20120303_MAM978.gif” captiontext=”Oil fields in Saudi Arabia’s restless Eastern Province (Map: The Economist)”]

According to Al-Rasheed, a significant part of Saudi counterrevolutionary strategy has been to exaggerate sectarianism within society, which has fuelled conflict based on religious differences between the majority Sunni population and minority Shi’a. The strategy of sectarianism sparked a discourse against the Shi’a population as a means of reinvigorating the loyalty of the Sunni majority. So far, it has been largely successful. (Al-Rasheed, 2011).

When in Doubt, Blame Iran

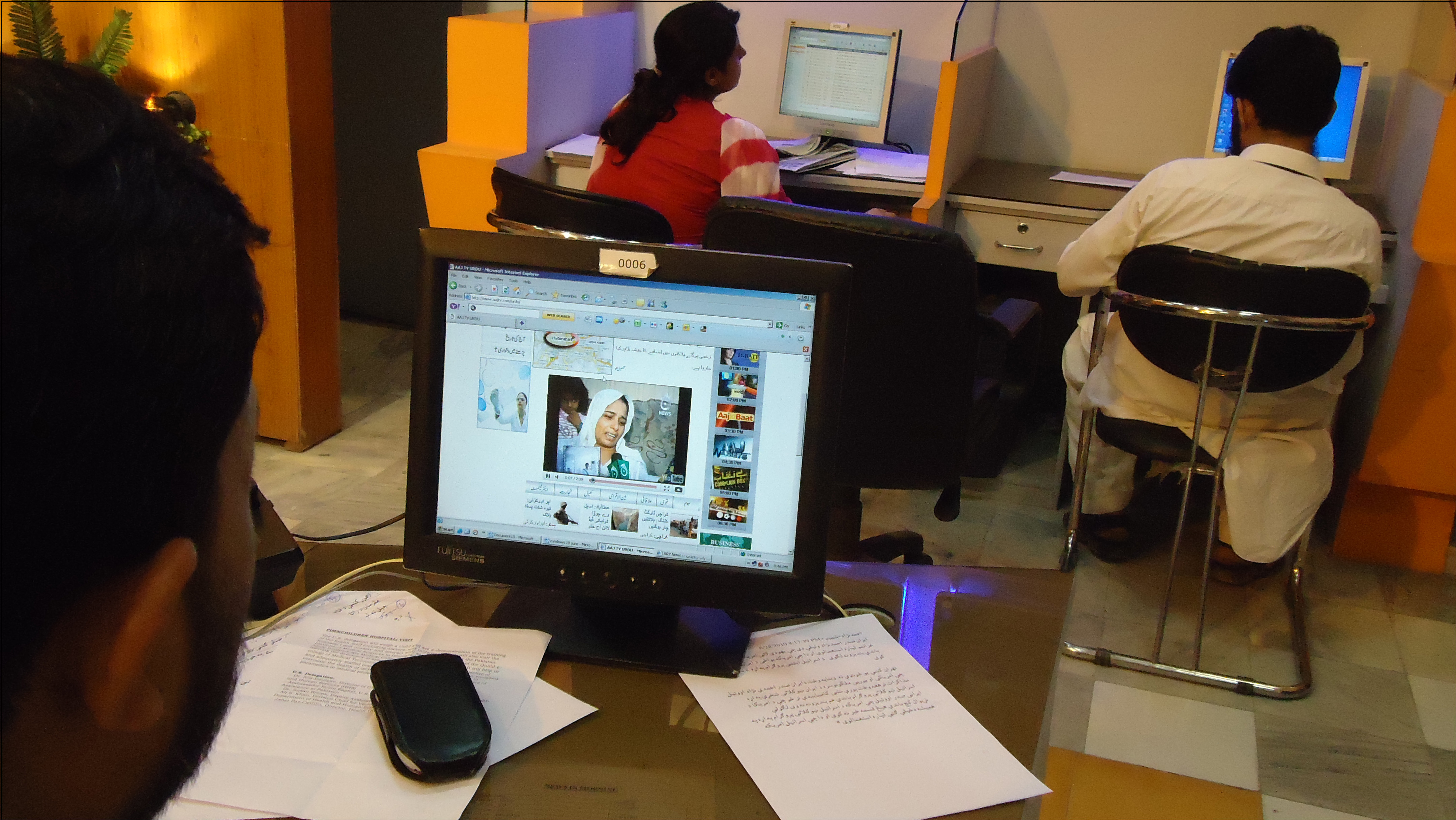

Saudi Arabia has also been heavily involved in silencing protests in its neighbour Bahrain. Saudi troops entered Bahrain in March 2011 in an attempt to help quell protests that had been ongoing for two months. The manner in which the House of Saud led the GCC invasion of Bahrain—a majority Shi’a state ruled by a Sunni monarchy—underpins the threat Saudi Arabia faces and how it is prepared to confront it.

The Saudi government has tried to portray the uprisings in Qatif and Bahrain as the work of Iranian subversion in the Kingdom. The GCC met this week to discuss the possibility of increased unity between all of its member states. Many analysts see this move as an attempt by the Gulf Arab states to fight back against their regional rival. It also provides Saudi Arabia with an opportunity to entrench its role as a Sunni hegemon.

Iran responded to the GCC meeting with an increasingly hardline tone, calling for renewed protests in Saudi and Bahrain. Although it is clear that there is Iranian support for the protests in Qatif and Bahrain, it would appear that the Saudi and Bahraini governments are playing the Iran card in order to justify taking further action against the protesters. Given the harsh realities faced by the Shi’a populations in both countries, it seems highly unlikely that the protests are the work of the Iranian government and can better be understood as a response to serious and systematic repression and human rights abuses.

The growing protests in Qatif are not the first instances in which the Arab Spring appears to be penetrating Saudi Arabia’s borders. In 2011 protesters attempted to organize a ‘Day of Rage’ on March 11 of that year. By most accounts, it was a failure. Not only did the ‘Day of Rage’ not materialize, many prominent Sunni Islamist groups within the Kingdom renewed their loyalty to the royal family in the aftermath of the attempted demonstrations. The lack of support from Al-Sahwa—the most prominent Saudi Islamist group—is not the only reason for the failure of the March 11th movement. It appears that most citizens prefer the current arrangement: exchanging political liberty for the promise of security and economic prosperity—a trend that has been evident within the country for decades. (Al-Rasheed, 2011).

Until now, oil money has equipped the regime with the ability to co-opt the religious elite into legitimizing their secular political moves in the name of Islam; provide welfare and economic opportunity to their subjects in return for complete submission to their authority; and find and discipline anyone who did not fall in line. Unfortunately for the ruling elite, the price of oil on the world market can be highly unstable, with prices rising and falling due to forces largely outside the control of the Saudi government.

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”320″ imgsrc=”http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Guardian/Pix/pictures/2011/3/9/1299703735715/Saudi-protesters-in-Qatif-007.jpg” captiontext=”Sectarian tensions still simmer despite the absence of widespread protest”]

Maintaining a Balance

Unstable oil revenues and growing disenchantment among the country’s Shi’a minority could mean serious trouble for the royal family in the future. The Saudi government would be wise to focus its efforts at home. Unrest in Qatif is clearly growing and to date shows no sign of stopping. Rather than trying to place the blame for the instability in the eastern province on its regional rival Iran, the ruling family needs to open the political space and address the issue of the treatment of the Shi’ite minority within the Kingdom.

The time to do this is now, while King Abdullah—often labeled as reform-minded and pragmatic by observers—remains in power. The heir to the throne and head of the Interior Ministry—Prince Nayef—is largely viewed as a hardliner and anti-Shi’ite, unafraid to use repression to quash protests. If his succession to the throne were to take place while divisive sectarianism within the country is at an all time high could mean disastrous results for the Kingdom.

References

Al-Rasheed, M (2011). “Sectarianism as Counter-Revolution: Saudi Responses to the ArabSpring” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 11 (3) pp. 513-526.

Kamrava, M (2011). “The Arab Spring and the Saudi-Led Counterrevolution”. Orbis 56 (1) pp. 96-104.

Lynch, M (2012). The Arab Uprising: The Unfinished Revolutions of the New Middle East. New York: Public Affairs