On October 13, 2021, the European Union unveiled its new Arctic policy, which focuses on three main objectives. First, the EU claimed it would contribute to the safety and stability of the Arctic by maintaining peaceful and constructive dialogue and cooperation. Then, it recognized the necessity to take strong action to tackle climate change and address the regional challenges stemming from it. Finally, the policy supports the inclusive and sustainable development of the Arctic regions, centring it around local indigenous peoples and women. At the same time, NATO has yet to shape and embrace a common Arctic strategy with respect to its member states. Thus, this article will discuss how the new EU Arctic policy could resonate with NATO interests in the Arctic. While the EU’s priorities remain similar to those established in 2016, there are some new characteristics in its 2021 Joint Communication.

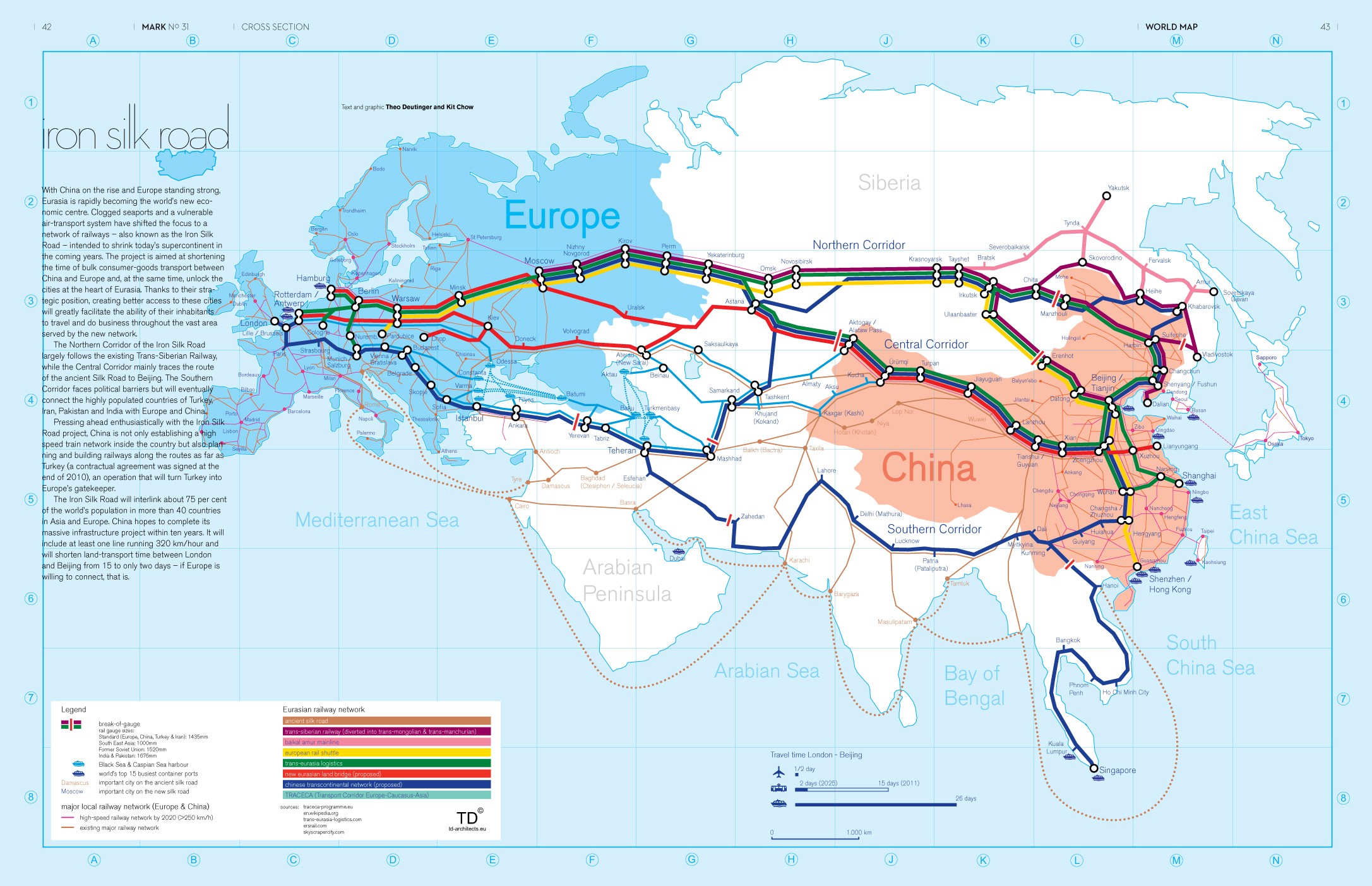

First of all, the EU clearly defines itself as a geopolitical power and the Arctic as an area of growing tensions and geopolitical competition. Along with climate change, new challenges and opportunities are emerging in the broad Arctic. On the one hand, global warming leads the sea ice to shrink and melt, disrupting the ecosystems of oceans and leading to rising sea-levels. In addition, permafrost thawing accelerates climate change even further. On the other hand, the disappearance of sea ice allows for the development of economic and defence interests, such as new shipping routes like the Northeast Passage and critical infrastructures. Non-Arctic countries are becoming increasingly interested in the Arctic, as showcased by China and its investments in building a “Polar Silk Road.”

To portray itself as a geopolitical power, the EU explicitly states that it has “strategic and day-to-day interests” in the Arctic region. To pursue said interests, the EU reiterated its application for the status of Arctic Council Observer and its willingness to enhance its contribution to Arctic Council Working Groups. At the same time, the European External Action Service created the post of EU Special Envoy for Arctic Matters and announced the creation of an office in Greenland. In its communications, the EU reiterated that cooperation with partner countries and NATO is essential to ensure a peaceful and prosperous Arctic. As such, the EU stated it was committed to “cooperate with NATO on strategic foresight” and intelligence-sharing through different tools, such as the EU’s Satellite Centre (SatCen) and Copernicus Emergency Management Service. Through its assertive claim to be a geopolitical power concerned with growing tensions in the Arctic, the EU positioned itself as a strong and reliable partner for NATO. Furthermore, this assurance could push NATO to develop its own Arctic strategy, and, together, they could be mutually supportive.

Secondly, building on its self-recognition as a geopolitical power and economic strength, the EU acknowledges that it “shares the responsibility for global sustainable development,” notably in the Arctic. While the Arctic states (namely Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the US) should be the primary actors to address the regional challenges, the EU recognizes that these challenges “can be more effectively addressed through regional or multilateral cooperation.” As such, and considering that three Arctic states are also EU member states, the EU believes it should lead by example through legislations at the European level. In the Arctic, 31% of CO2 and 16.5% of black carbon emissions are produced by maritime transport from EU members. As part of the European Green Deal (EGD), the EU and its member states are committed to drastically reduce their carbon and environmental footprint, specifically in maritime transport. Also, a significant amount of the world’s reserve of minerals and raw materials is found in the Arctic. As part of the EGD, the EU is committed to building a sustainable supply of minerals and raw materials in the region while respecting local communities. In this sense, acknowledging its own responsibility to tackle challenges in the region strengthens the EU’s call for cooperation and multilateralism, opening the door for more coordination with NATO.

Finally, in its Arctic policy, the EU advocates that fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal) in the Arctic must stay in the ground and states that the European Commission will work towards a “multilateral legal obligation not to allow any further hydrocarbon reserve development” in the region. Furthermore, the EU is committed to building a consensus against the purchase of such fossil fuels if they were produced. Although very assertive, this policy follows the direction that EU Arctic states set themselves. In its 2021 Strategy for Arctic Policy, Finland states that “the opening up of new fossil reserves in Arctic conditions is incompatible with attaining the targets of the Paris Agreement.” Similarly, even though it is the EU’s biggest oil producer, Denmark announced the ban of fossil fuel extraction in the North Sea to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Canada and the US are also sensitive to the challenges caused by oil and gas in the Arctic. In 2016, the former issued a moratorium on fossil fuel production in Arctic waters, while the latter suspended oil drilling licenses in Alaska in early 2021 under the new Biden administration. However, other Arctic states, such as Russia and Norway, denounced the EU’s goal regarding oil and gas. For instance, Norway stated that the fossil fuel sector would be “developed, not dismantled,” although announcing to cut carbon emissions by 55% by 2030. Thus, issues around fossil fuel in the Arctic remain contentious and subject to potential changes, lessening the opportunities for a NATO-wide agreement or EU-NATO cooperation on the matter.

To conclude, the EU Arctic policy opens the door for further EU-NATO cooperation. Whereas cooperation on the first two points could be relatively easy to achieve, namely recognizing the Arctic as a region of geopolitical competition and acknowledging the shared responsibility for global sustainable development, NATO members’ diverging interests in fossil fuel exploitation could prove EU-NATO cooperation in the Arctic more difficult. Still, prior to any EU-NATO cooperation in the region, NATO should create its own Arctic policy, which proves challenging. Indeed, while the NATO Strategic Direction-South Hub was created already in 2017, the “High North” was referred to only once in the latest NATO Communiqué after the Brussels Summit. Thus, NATO’s new Strategic Concept, coming in 2022, will be essential to assess whether and to what extent NATO and the EU will be able to cooperate in the Arctic.

Photo: USS Oscar Austin transits the Arctic Circle (September 4, 2017), by Official U.S. Navy Page via Flickr. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.