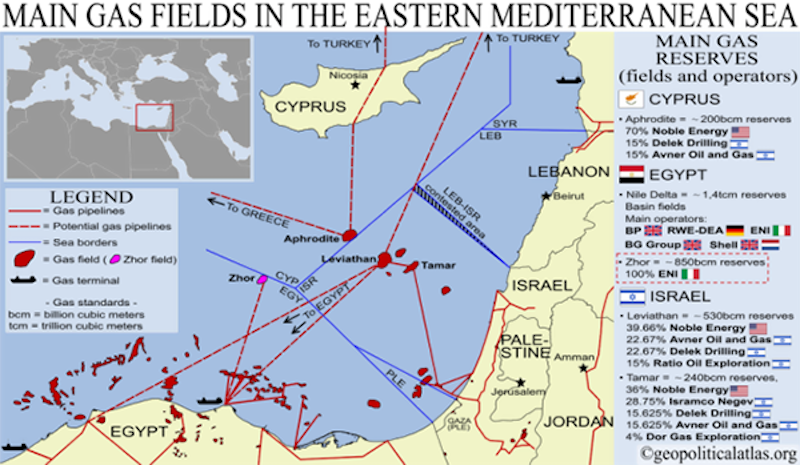

The continuing news about the Syrian Civil War tends to obscure the emergence of the East Mediterranean basin as a potentially significant energy-producing region, where military clashes in coming months cannot be ruled out. Recent energy-related success stories in the region include Egypt’s offshore gas discoveries and the continuing growth of Israel’s offshore gas projects, as well as promising developments offshore from Cyprus and possibly also Lebanon.

The East Mediterranean is the only NATO region where uncertainties about both security and energy combine to threaten the stability of strategic relations. Turkey’s recent moves to project military power have increased the uncertainty over security of energy supply, causing concern amongst its neighbours such as fellow NATO member Greece, but also Israel and Egypt.

Rich in energy resources, the East Mediterranean waters are now being explored and developed after decades during which strategic confrontations rendered their exploitation politically impossible. Yet the continuing Syrian disaster creates possible fall-out for countries in the region, including Israel, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, as well as for the divided island of Cyprus.

In 1974 the northern third of Cyprus was occupied by Turkish forces, who remain there. This occurred during an invasion that followed the coup against Archbishop Makarios by ethnic Greeks seeking to unite the island politically with the Greek mainland. Many Turks from the Anatolian peninsula have immigrated to northern Cyprus since then.

On August 28 news emerged that the Turkish armed forces are considering construction of a sovereign naval base in the Turkish part of Cyprus and that the Turkish navy has submitted such a proposal to the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the base. Such a base would facilitate military activities in (Greek) Cypriot offshore areas, where American and European oil and gas majors are now planning exploration activities.

Tension from the ongoing confrontation between Cyprus and Turkey is made worse by off-and-on low-intensity clashes between Turkish and Greek armed forces. The Greeks report harassment of Greek fishermen by Turkish vessels on a regular basis in the eastern Aegean Sea.

Greece is concerned by the announced Turkish plans to drill for gas deposits in the East Mediterranean, including in Cyprus’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Most of the energy reserves that Turkey wishes to claim are in disputed areas, such as near Greek islands or Cyprus, or in the maritime zones of others.

State-controlled Turkish media have recently stepped up their efforts in support of Ankara’s claims on several offshore areas. Most sensitive is the maritime region to the south of Cyprus. Earlier this year, Turkish warships blocked exploratory vessels of the Italian company Eni. These vessels had sought to conduct drilling in waters that Turkey asserts belong to the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, which no state other than Turkey recognizes.

Turkish officials have reiterated that Ankara has no plans to back away from its energy plans in the East Mediterranean, including maritime areas areas under Cyprus’s jurisdiction according to the UN Convention on the Law of Sea, to which Turkey is however not a party.

The drilling vessel Fatih, docked in the southern Turkish city of Antalya, will most likely head east this autumn between the Karpas peninsula in northern Cyprus and the Gulf of Iskenderun. Turkey’s seismic vessel Barbaros Hayrettin Pasa is already surveying this region.

Other East Mediterranean countries such as Israel and Egypt are unsympathetic to Turkish claims but hopeful to avoid military force, the use of which they do not, however, renounce for themselves. Ankara has warned several European governments not to support the hydrocarbon exploration activities being conducted by Cyprus in the East Mediterranean.

In October the American energy major ExxonMobil plans to begin drilling for gas in Block 10 of Cyprus’s EEZ. The French major Total also is set to start drilling in February 2019. Previous French operations have already been constrained or blocked out-right by Turkish naval threats to their vessels approaching Cypriot waters.

Strong economic growth over the last number of years has supported Ankara’s overall strategy. However, increasing unemployment and social unrest accompanied by decreased purchasing power could force unconventional measures, not excluding military adventures to distract the public. The ongoing continual worsening of Turkey’s economic situation threatens the country’s social fabric and possibly even its role within NATO.

Turkey’s recent emergence as an investment destination for sovereign wealth funds and institutional investors created a boom in infrastructure and real estate projects. The latter, however, are financed by external debt, which now threatens the country’s economic fabric.

At the same time, Ankara needs to reassess its options of energy supply security as Tehran is removed from circulation. American sanctions on Iran will diminish Turkey’s capacity to receive oil and gas from Iran, although Iran’s oil has in the past been rebranded as Iraqi and sold worldwide anyway. Erdogan’s strong support for Hamas, Hezbollah, the Muslim Brotherhood, Syria and Iran likely exclude LNG import options from Israel and Egypt.

Turkey is facing a domestic financial and economic crisis with its currency plunging at the same time as its ongoing military operations in Syria head for a confrontation around Idlib. It is not to be excluded that the fall-out leads to an opportunistic military move in offshore waters. That would in turn threaten direct confrontation with other NATO allies, regional powers such as Egypt and Israel, or even Russia.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.