As NATO’s seventy-fifth anniversary approaches, the alliance finds itself confronted by Russian revanchism and invasions in Eastern Europe, growing anti-Western alliances in Asia, and tenuous and uncertain political trends in many member nations. Yet to NATO, this is familiar territory – much of the same dynamics are occurring now as during the Cold War (1947-91), an ideological conflict which saw the triumph of collective security over communist threats.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) was formed in 1949 as a defensive military alliance between twelve countries: Belgium, Canada, the United States, Britain, France, Norway, Iceland, Portugal, Italy, Luxembourg, Denmark, and the Netherlands. The alliance would expand ten times over the course of its existence, to include thirty-two members as of 2024. Formed to counter a potential Soviet invasion of Western Europe in the wake of the Second World War, NATO’s strength rested on conventional military defence, as well as nuclear deterrence articulated through a policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) in the event of a general nuclear exchange.

Yet NATO’s success in winning the Cold War rests on a negative: that a direct shooting war did not break out. Nuclear conflagration did not occur. While there are a variety of reasons to explain the lack of a NATO-Warsaw Pact conflict, and one may indeed argue that NATO was not entirely successful in preventing Soviet incursions into Europe (Hungary, 1956; Czechoslovakia, 1968), NATO – and specifically the principle of collective defence under nuclear deterrence – was responsible for maintaining the peace at critical points in the East-West relationship.

The Early Cold War, 1949-1968

The first twenty years of the Cold War was a fluctuating period of geopolitical relations between East and West: heightened tensions were often followed by détente and rapprochement. This period saw some of the darkest days of the conflict, which served to reinforce NATO’s mission as a necessary and vital one. This was first given focus after Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, for instance, in which the USSR invaded its own satellite nation to dispel popular anti-communist uprisings. While the Alliance remained concerned with the degree to which Premier Khruschev was prepared to use military force in pursuit of Soviet political and ideological objectives, NATO’s policy of massive retaliation was ill-suited to dealing with political change and limited military engagements on this scale.

This would change during a far more serious crisis – the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. In retaliation for the United States’ positioning nuclear-tipped Jupiter missiles in Turkey, the Soviet Union stationed their own medium-range ballistic missiles in Cuba. When the US blockaded Cuban waters to prevent more missile deployments, NATO responded by increasing its maritime and air-patrol duties to supplement American forces. Yet even so, NATO’s potential responses were limited to defensive options on a large scale: fielding a nuclear-capable force to ensure retaliation, but which constrained their ability to react to smaller-scale scenarios. While the Cuban Missile Crisis was resolved peacefully, NATO entered a period of reflection and adjustment, emerging with a new flexibility to respond to Soviet provocations more adeptly.

The Later Cold War, 1968-1991

The second half of the Cold War was marked by a general reduction in geopolitical tensions between NATO and the Soviet Union following the rise of Leonid Brezhnev to power in the late 1960s. While the USSR invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, NATO could not intervene over a non-member’s sovereignty. Rather, the Alliance continued to focus on mutual interoperability, economic and military cooperation, and the development and fielding of new types of nuclear weapons to maintain its strategic edge, even as the US and USSR reduced their overall stockpiles following the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT) of the 1970s.

By the early 1980s, however, relations had once again deteriorated to the point that a potential European war seemed likely. Unlike in the early 1960s, here the Alliance began to diverge from the Soviets in terms of military capacity, flexibility, and overall economic health. Peaceful economic cooperation and mutual support had restored European economies to strong footings, while the centralised system of the USSR was now unwieldy and slow. As NATO could field newer and more advanced platforms, and better-trained servicemembers, the USSR began to fall behind in quality, relying more heavily on the threat of massed (but inexpensive) troops and older equipment, or expensive nuclear forces. Such a high commitment strained the Soviet economy almost to breaking, a fact which Premier Gorbachev used to pursue policies of détente with the West after 1985.

By 1989, as shown by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the USSR lacked the ability to prevent mass protests, demands for political participation, and emigration, and as each satellite nation claimed its independence, by 1991 even the Soviet Union was dissolved in a relatively peaceful fashion. NATO had achieved its objective: it had prevented a third world war. Yet it was not through diplomatic negotiations, policy initiatives, or high-level summits that such a result occurred, although those were undeniably important. Rather, it was by NATO’s very existence that peace was maintained.

NATO and Reinvention

Indeed, to remain relevant, the Alliance reinvented itself several times over the course of the conflict – from providing a bulwark against a conventional invasion, to massive nuclear retaliation, to offering flexible responses to a variety of situations, NATO proved more nimble than its Soviet counterpart, the Warsaw Pact; and although there is much value in economic arguments for the decline of the USSR, NATO’s military strength must be assessed as a significant contributing factor.

Now, NATO is called on to sharpen and reevaluate its focus once more. Current challenges appear similar to those encountered during the Cold War, but which now occur much more quickly, and across a variety of domains (both physical and electronic). Yet, if there is one thing the Alliance is capable of, it is the capacity for rejuvenation and reinvention. With new members, and an increasingly proactive commitment to defend ‘every inch’ of its territory, NATO will likely remain useful and relevant for many years to come.

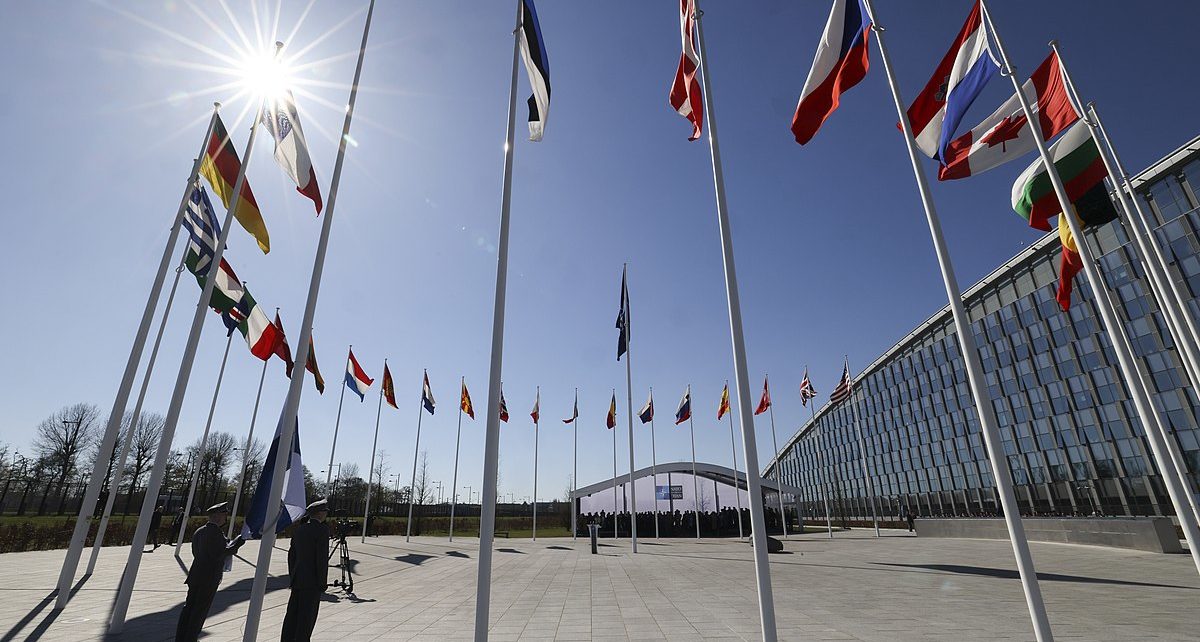

Photo: ‘Finland Flag Raising at NATO Headquarters’, 4 April 2023; UK Government photo taken by Rory Arnold, licensed via Creative Commons permission CC BY 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.