West along Independence Avenue; north on 14th Street; left on Constitution Avenue; around the Ellipse to the White House: the route of the Women’s March on Washington was simple to follow. The path to change will be harder to find.

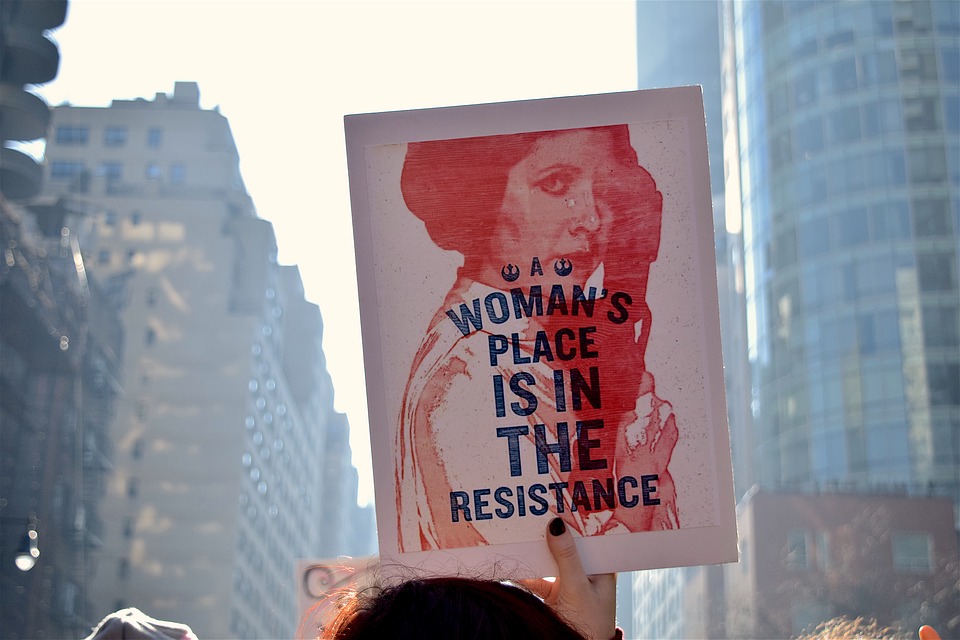

Saturday, January 21 saw a huge outpouring of support for the Women’s March, a global protest against US President Donald J. Trump and the forces that elected him. In the American capital, an estimated 500,000 people thronged the streets, while between three and four million others took part in roughly 650 sister events around the world. As a demonstration of solidarity and unity of purpose, the event was an unqualified success. As a call to arms, its effect is an open question, and the organizers aren’t waiting for an answer. They have issued a manifesto, ’10 Actions in 100 Days,’ and framed a modest mandate: to make history.

After President Trump’s first week in office, that will be easier said than done. If the marchers of 2017 want to influence the America of 2018 (and beyond), they have a few hurdles to clear.

The first is process. In their first action, the Women’s March on Washington is calling on American supporters to write to their Senators about the issues that matter to them. This step is going to do more for the marchers’ energy than it will for the nation’s politics. The Republican Party is under enormous pressure to deliver. It has been handed control of the legislative and executive branches of government, along with a transformational mandate that ranges from health to infrastructure to border security. America’s Congressional approval is still stuck below 20%, and the country just fought an election that called out the political establishment for complacency and inaction. Republican Senators and Representatives cannot afford to stall.

That is not to say that Trump had GOP lawmakers’ unqualified support. During the campaign, he was criticized for his language and his platform; now that he is in office, he has been chastised for his pronouncements on the intelligence community, Russia, torture, and illegal voting. After the President issued an executive order barring immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries, 20 Republican lawmakers opposed the order or refused to endorse it. However, presidents tend to be most effective in their first 100 days in office, and the Republican Party will do its best to maintain a united front. The longer they succeed, the more difficult it may be for the Women’s March to maintain its momentum.

Even success has its risks. President Trump swept into office promising to end the power of the Washington establishment. Now that he is in charge he will find it increasingly difficult to blame legislative deadlock on the country’s political leadership, but he could find a new scapegoat in the Women’s March. If the movement succeeds in organizing itself against President Trump, the Republican Congress, and their agenda, it could easily become a rallying point for the opposition—and the target of blame.

That risk hints at a further challenge: the attitude that Trump’s administration and its supporters take toward their opponents. President Barack Obama used to say that activists should direct their energy to getting “at the table” with policy-makers. President Trump does not seem to believe that there is a table. Early on the day after the march, he tweeted “Watched protests yesterday but was under the impression that we just had an election! Why didn’t these people vote?” Although he followed up with a more conciliatory tweet, Trump never offered any response to the march’s message.

Not that he was completely silent. On Sunday, January 22, the new American government gave its reply to the Women’s March by reinstating the Mexico City Policy. That program, also known as the Global Gag Rule, bans federal funding for any services abroad that provide information about, or access to, abortions. It was a frosty reply to the marchers, who, among other things, walked in support of reproductive rights. It was also a sign of greatest test they will face: not how to succeed, but how to deal with reversals.

Then there is the question of solidarity. The Women’s March on Washington was framed as a moment for citizens to stand together in defense of groups that felt threatened by the incoming administration. Native Americans, African-Americas, Hispanics, immigrants, and LGBTQ people were placed at the centre of this mission of solidarity. Yet on the day of the march, the crowds that filled the streets were largely white, and their story of feminist triumph—for some critics—left little room for recognizing groups at the margins.

When it comes to political activism, whiteness can be useful, offering power and a platform. Among other things, white privilege encompasses better education, greater wealth, and 80% of the seats in Congress. It was even suggested that white participation in the Women’s March smoothed its passage through police-filled streets (notably, nobody was arrested for marching). However, the dominance of white participation in the Women’s March may make it difficult to keep non-white stories at the centre of the narrative. And if non-white citizens suffer disproportionately under President Trump, will their white neighbours speak out? Will they notice?

The question, then, is not whether white voters can demonstrate solidarity, but whether they will. Beyond the frustration of legislative defeat and the slow grind of time, the Women’s March has to contend with the distance between the white experience of Trump’s America, and the non-white experience. There are signs that that distance can be closed; Trump’s immigration executive order produced howls of anger and a wave of protests around the country and across the globe. What happens next time? Will white citizens push back if the Justice Department stops filing cases to protect minority voters? Will they call out racism in the streets? Perhaps most importantly, will the next two (or four) years change the way that whites (including white women) voted? If the Women’s March in Washington is going to be remembered as more than one day in history, the answer to those questions had better be yes.

Photo: “A woman’s place is in the resistance” at the Women’s March on Washington (January 21, 2017), via Pixabay. Licensed under Public Domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.