Western states face a quandary of whether to prioritize economic growth or values such as human rights and democracy in dealing with China. Emphasizing one over the other can have ramifications both domestically and internationally. If human rights are prioritized over trade, Western countries may lose out on valuable opportunities offered by China’s economy. If trade takes precedence over human rights, Western governments can face allegations that they have abandoned the very values they claim to cherish. Some recent hiccups in the United Kingdom’s relationships with China can help us understand how the relationship between the West and China has changed as China’s political and economic influence has grown.

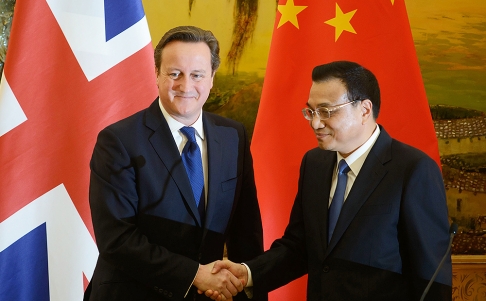

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited the United Kingdom from June 16-19, reciprocating a visit by British Prime Minister David Cameron to Beijing in December, 2013. The Premier’s visit comes after a period of frosty relations between the United Kingdom and China. In December, 2012, both Prime Minister Cameron and British Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg met with the Dalai Lama in London, a move that infuriated the Chinese government. China claimed that Mr. Cameron and Mr. Clegg were interfering in its internal affairs; they see the religious leader as trying to encourage the breakup of China through Tibetan independence. In response to the Dalai Lama’s London visit, the Chinese government cancelled the Prime Minister’s visit to Beijing the following April, saying that high-level Communist Party of China (CCP) officials were “unavailable.” With trade between the United Kingdom and China being at an all-time high at that point, the Cameron government decided to rethink their position on China’s human rights record.

Mr. Cameron visited Beijing in December 2013 and it appears that the two sides have moved past their differences. Many expect approximately $30 billion USD worth of economic deals to be signed during Mr. Li’s current visit, as well as the announcement of a streamlined visa process for Chinese tourists visiting the UK by the British Home Office. This was to address complaints by Chinese officials and tourists and increase Britain’s share of free-spending Chinese tourists.

France currently receives around nine times more Chinese tourists than the UK, partially due to the fact that the UK is outside of the Schengen visa area and requires a separate visa for Chinese visitors. With Chinese tourists expected to spend more than ever abroad (they spent $129 billion USD, $40 billion USD more than Americans did), not accommodating such a growing force in the tourism industry could be disastrous for the UK and other Western states with large tourism industries (like France and the United States).

China’s rise to become the world’s second largest economy appears to have given it considerable leverage in dealing with criticism of its human rights record. Denying access to its massive consumer base and economic resources can potentially be very painful for countries that don’t play by its rules on human rights.

The United Kingdom appears to have decided that it will put economic growth first when dealing with China and it is not alone. Canada had its relations frozen with China in 2007 after a meeting between Prime Minister Harper and the Dalai Lama, with relations only recently recovering as trade interests appear to have outweighed human rights interests.

In these times of low economic growth and austerity, it appears trade has trumped values in many Western countries. This does not mean that human rights are off the table, as the Cameron government has refused to rule out human rights issues being raised in China-UK discussions. Hope for a firmer stance on human rights in China may not be dead, but until Western government balance sheets improve, it sure seems as if it is.