Turkey has always had serious reservations with regards to the role of the Kurds, the second largest ethnicity in Turkey, in Syria and Iraq, and what their assertiveness would mean for Turkey. Although ad-Dawlah al-Islāmiyah fī ‘l-ʿIrāq wa-sh-Shām (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, ISIS) has been declared an enemy by every state and non-state actor around it, Turkey has viewed the active role of the Kurds against ISIS with suspicion, perceiving there to be an underlying motivation in the long term against Turkish sovereignty. Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (Kurdistan Workers’ Party, PKK), a designated terrorist group, through its armed wings, Hêzên Parastina Gel (People’s Defence Force, HPG), has been locked in an intense separatist guerrilla conflict with the Turkish state since 1984, so far claiming more than 40,000, mostly Kurdish, lives.

Apart from Turkey, the Kurds are active in Iraq, Syria and Iran either as a rights movement or as a government. In Iraq, Hikûmetî Herêmî Kurdistan (Kurdish Regional Government, KRG) is the governing body of Iraqi Kurdistan; dominated by the Partîya Demokrata Kurdistanê (Kurdish Democratic Party, KDP) and Yekêtiy Niştîmaniy Kurdistan (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, PUK), both parties have their respective Peshmerga forces with tensions between them, yet collectively provide security for the Iraqi Kurdistan. The PKK has been at odds with the KRG which sees Turkey as a trading partner rather than as an opponent, although the KRG has been assisting other Kurdish elements in combatting ISIS in the region.

In Syria it is the Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat (Democratic Union Party, PYD) with its armed wing, the Yekîneyên Parastina Gel (People’s Protection Units, YPG) has faced the ISIS threat head-on, garnishing international acclaim. The PYD was founded by the PKK in 2003. In 2011 the Syrian regime brokered a deal with the PYD hoping to “temper” Kurdish opposition within Syria while redirecting opposition to Turkey, whereas the PKK saw it to be a new opportunity for the Kurdish movement. In 2012, the PKK was helping the PYD set up armed militias in the wake of the Syrian revolution.

This interconnectivity between the PYD and the PKK worries Turkey and directly influences its current policy in Syria. They are wary that even though the PYD is combatting ISIS, another threat, they are aligned with the PKK which has been involved in a bloody confrontation with the Turkish state for over 30 years. A rudimentary parallel which can be drawn to better outline Turkey’s suspicion towards the PYD is the West’s reservation towards Jaysh al-Fateh (Army of Conquest), which has proven to be effective force against both al-Assad and ISIS, due to the al-Qa’idah affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (Nusra Front) having a role in it. Thus, a PKK affiliate, no matter how effective of a fighting force against ISIS, does not serve in Turkey’s interest, in the same way that al-Nusra’s opposition to ISIS does not grant it amnesty from coalition airstrikes.

Another Kurdish entity operates within Iran, the Partiya Jiyana Azad a Kurdistanê (Party of Free Life of Kurdistan, PJAK) with its armed wing, the Yekîneyên Parastina Rojhilatê Kurdistan (East Kurdistan Defence Units, YRK). PJAK, although it insists it is different from the PKK, shares the same ideology and methodology as its Turkish counterpart. Sharing leadership and membership they pose a threat to both Turkey and Iran. A founding member of PKK, Cemil Bayik commented in 2006 that “the PKK is the one who formed PJAK, who established PJAK and supports PJAK”. The proximity and connectivity between these two groups create overlapping interests between Turkey and Iran, both seeking to counter Kurdish movements within their regions.

Iran has criticized Turkey’s recent actions against the Kurds. The Iranians may be attempting to capitalize on the international outcry against Turkey for its bombing of PKK targets, Iran’s University of Kurdistan has opened a Department of Kurdish Language and Literature for the first time. Nevertheless, Kurdish sources reported that recently Iran shelled a Kurdish village near the Iraqi border. Although Iran may be seeking to woo Kurdish elements domestically and abroad, they are also wary of PJAK’s potential influence in the wake of Kurdish opposition to ISIS and what it means for Iranian Kurdistan.

Although groups such as the PKK, PYD, PJAK have contributed towards counteracting the spread of ISIS, it has not benefitted them regionally as the countries within which they traditionally operate view them as domestic threats. To the Turkish, Syrian, Iranian and even the Iraqi states the Kurdish struggle is unwelcome as it results in the loss of sovereignty for each state mentioned. The interconnectivity of many of these groups associates them with the controversial PKK, designated as a terrorist organization in the US and abroad. Even if they may be countering ISIS, their association with groups working against the Turkish state may be the biggest factor in the long term failure of the Kurdish project in the Middle East.

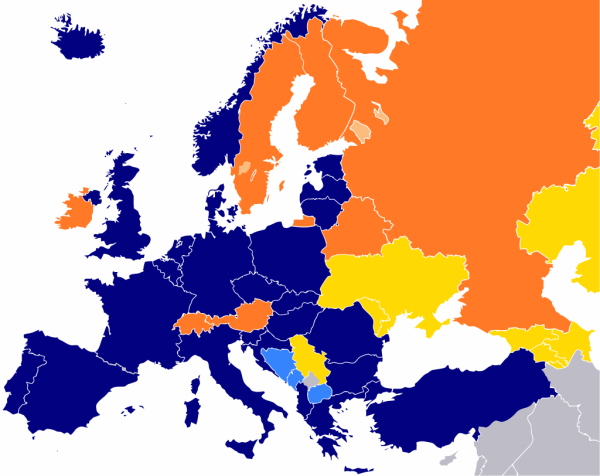

The removal of the terrorist designation from the PKK seems to be unlikely as Turkey is a major partner for NATO in counterbalancing Russia and upsetting Turkey may result in a loss of strategic depth for the West, especially now when Russia is posturing aggressively across its former spheres of influence. The Kurds have, once again, been caught in a conundrum which they cannot get out of because there are larger stakes at hand. For now, the Kurds are being used as a fighting force against ISIS, but will be likely left disappointed once all is said and done.