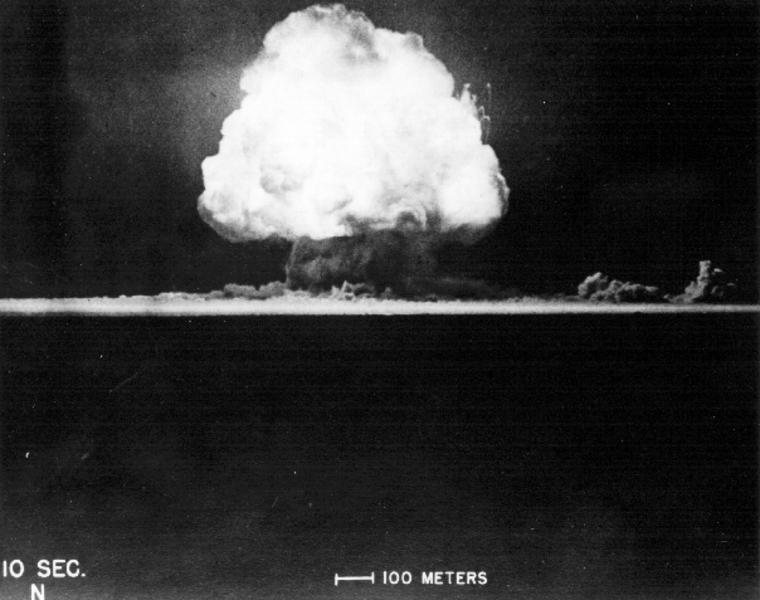

It has been seventy-five years since the start of the nuclear age. The United States was the first country to witness the destructive power of nuclear devices at the Trinity Test on July 16, 1945. The weapons’ full potential was revealed nearly a month later with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The prospect of nuclear conflict was no more immediate than during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, where tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States pushed global security to the brink of ruin.

As the Cold War years progressed, growing arsenals compelled nations to negotiate arms control agreements. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) of 1970 was one such accord. Notably, five nuclear-weapon states – the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom – settled to pursue disarmament and refrain from expanding existing stockpiles. More importantly, the Cold War era set the foundation for bilateral cooperation between Russia and the United States – countries that today hold over 90 percent of the world’s nuclear arsenal.

But in recent years, Russia and the United States have been reluctant to initiate dialogue on deterrence, and arms control agreements between the two superpowers have begun to erode. The termination of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was a significant regression. Enacted in 1988, the INF treaty abated tensions between the Soviet Union and NATO countries by eliminating an entire class of nuclear weapons. The Treaty showed signs of decay when Russia started producing and deploying prohibited ground-launched missiles. Despite efforts to bring Russia back into the ambit of the Treaty, the country’s ongoing violation prompted the United States to withdraw from the agreement on August 2, 2019. After the Treaty’s collapse, both countries seized the opportunity to develop INF-range missiles. Only 16 days after the Treaty’s downfall, the United States initiated a surprise test launch with weapons previously banned under the Treaty.

The demise of the INF Treaty is made all the more concerning while the fate of the New Start Treaty hangs in the balance. Signed in 2010, the New Start Treaty limits Russia and the United States to 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers apiece, and it restricts both arsenals to 700 deployed missiles and bombers. The agreement also places a ceiling of 1,550 on nuclear warheads, a near 30 percent reduction from the previous SORT agreement. Although New Start is set to expire in 2021, efforts from Washington and Moscow to renew the deal have been lacking. While Russian President Vladimir Putin is committed to extending the agreement for another five years, President Trump has not been so eager. If New Start is left to expire, there will no longer be a single legally binding arms control agreement between Russia and the United States, a reality that has not been apparent since 1972.

The exclusion of China from the New Start Treaty has contributed to Trump’s unwillingness to revive the deal. So far, China has been unreceptive to the United States’ desire to expand the bilateral scope of the New Start Treaty. Beijing was lately afforded the opportunity to amass a small number of INF-range missiles while Russia and the United States remained bound to the INF Treaty. In 2019, the Defense Intelligence Agency stated that, “Over the next decade, China is likely to at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile.” Although the country has begun to modernize its nuclear program, China’s stockpile is relatively insignificant. Resting at a meager 290 weapons as of 2019, China’s arsenal is dwarfed by the combined 12,675 arms housed in the United States and Russia. China’s nuclear activities do not warrant the termination of the New Start Treaty. Abandoning the Treaty would only further loosen restraints on the two largest nuclear stockpiles in the world.

Apart from China, other major powers have begun to modernize their nuclear capabilities. Pakistan, for instance, has the fastest growing nuclear arsenal in the world. Iran has also advanced its nuclear program. The country has lately sought to collect a range of ballistic missiles. Iran has used ballistic missiles against adversaries in Syria, and more recently, to target US forces in Iraq in retaliation for the killing of Qasem Soleimani. Efforts to reinforce nuclear non-proliferation in Iran were compromised when the United States withdrew two years ago from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, otherwise known as the Iran nuclear deal.

Three-quarters of a century have passed since the detonation of the first atomic bomb and much remains at stake for nuclear security. At the height of the nuclear age, armed states altogether had accumulated around 70,000 warheads. By the end of 2019, this number declined to roughly 13,865. While this is a sizable decrease, significant obstacles to nuclear disarmament prevail. Agreements like the New Start Treaty, intended to control weapons capable of considerable destruction, have begun to falter. Nuclear security is no longer at the forefront of diplomacy, instead, isolationism has given rise to an international arms race. In the years to come, a rules-based order of deterrence and stability must be the at the forefront of global nuclear policy.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.

Featured Image: “Trinity Test Mushroom Cloud” (1945), by Federal government of the United States via Atomic Bomb Test Site Photographs. Public Domain.