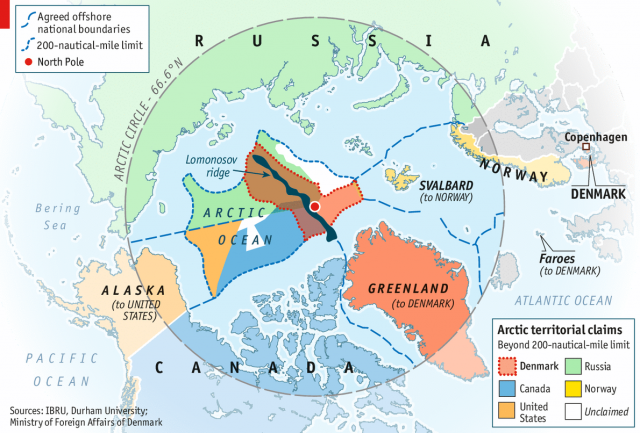

The rapidly melting Arctic is creating an opportunity for resource extraction and the expansion of shipping routes. In 2008, under the US Department of the Interior’s supervision, the United States Geological Survey estimated that 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30% of its gas is located in the Arctic Circle. Eight years later at the Arctic Assembly, Ban Ki-Moon warned that “on one single day last month, the Arctic ice cap melted at three times its normal rate, losing ice the size of England”. Last year, the UN’s World Meteorological Organization added that the Arctic ice cover is unusually thin, and large areas are susceptible to melting this coming summer. The opening of the Arctic has sparked a territorial dispute between eight states – Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States – who have territory north of the 60-degree latitude, five of which border the Arctic ocean. Observing the geopolitics of the Arctic as a whole, the situation unfolds into an array of complex relations, including a confrontation between NATO and Russia, various bilateral relations, and the involvement of international actors.

The Russian Defence Ministry recently allocated $24 billion as part of a state defence order of 2018. A major part of this allocation is towards rebuilding and Russia’s Arctic presence. As of May 21, 2018, Russia’s first sea-borne nuclear power plant has arrived in the Arctic, and Russian submarines are now permanently deployed there. This will provide electricity to an isolated Russian town across the Bering Strait from Alaska, which will benefit from a more permanent Russian presence, both civil and military. Furthermore, Russia’s missile cruiser Marshal Ustinov recently held firing drills in the Barents Sea, the new Sukhoi-30SM was integrated into the Northern Fleet, and Moscow’s deployment of the Tor and Pantsir air defence systems in white and gray Arctic camouflage showcase the preparedness of its operational Arctic military. Most importantly, NATO’s combined icebreaker force of approximately 31 ships, to clear the way for its warships, is no match for the Russian icebreaker fleet of more than 40 ships, some of which are nuclear-powered, giving them incredible range and endurance. Sweden’s reintroduction of conscription exemplifies the rising tensions over Moscow’s maneuvers in the Arctic. Observing current methods, Russia will look to develop their Arctic capabilities further by establishing more permanent bases Nevertheless, Russia’s Arctic development will be challenged by two major factors: (a) internal weaknesses, such as corruption, and (b) pressure from international actors and nations, such as NATO, Arctic Council, UN Environment Program.

NATO has largely prioritized the Eastern European region over security in the Arctic. Therefore, NATO’s Arctic military capacity and presence has been lacking, creating a vacuum for major actors such as Russia and even China to take hold in the region. Moreover, a swift collective response to Arctic challenges has been prone to difficulties within NATO, due to national priorities and bilateral negotiations. Even typically peaceful nations such as Canada and Denmark, for instance, have a long-standing argument on their Arctic delimitation. Although Canada and Denmark were able to reach an agreement on the Lincoln Sea boundary, Hans Island and the rest of Danish claims for the Arctic overlap with Canadian national interests. The dispute over a small, uninhabited barren knoll1.3 square km in size exemplifies the significance of the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait. This island demonstrates who holds control over the strait that connects the Arctic and the Atlantic Ocean, which might not seem significant in the current context of international trade, but may evolve into one of the key points of future navigation.

Canada’s slight rift with the US is a consequence of the ongoing dispute over the 21,000 square km overlap in the energy-rich Beaufort Sea, which holds vast hydrocarbon deposits, and more than 2 billion cubic metres of gas and oil. Canada claims that the maritime boundary runs along the 141st meridian as an extension of the territorial boundary agreed with the US, while the US argues that the boundary must be determined by using the equidistance principle, by tracing a line at an equal distance from the closest land point of each state. Conclusions of the delimitation will be determined by UNCLOS via the seabed shelf and will determine access to these resources. Comparatively, the Rockall dispute also highlights the lack of unity within the transatlantic alliance, since members including Iceland, the UK and Denmark (via the Faroe Islands), still cannot form an agreement due to the vast untapped resources in the region, and the importance of controlling the GIUK gap.

On the other hand, Russia has largely defined its Arctic coast delimitation on multiple occasions and is focused on expanding its influence further into the Arctic. Russia agreed with the US to delineate the Bering Sea, creating the Baker-Shevardnadze agreement, while also affirming the Russian authority of the Big Diomede Island and the US Little Diomede Island that lie in the middle of the Bering Strait. This provides maritime access to Russia on its east coast and the US on its west coast, from the Arctic to the Pacific. Furthermore, Russia resolved its dispute with Norway in the Barents Sea by signing a treaty allowing for new oil and gas exploration. It was Jens Stoltenberg, who was Norway’s Prime Minister at the time, who signed the agreement with Dmitry Medvedev in Murmansk, ending the border dispute and approximately splitting the Barents Sea claims down the middle. Furthermore, Russia utilized its agreement regarding Norway’s Arctic Archipelago islands of Svalbard to create the second largest settlement, Barentsburg, populated by Russians and Ukrainians, to act as a potential bargaining chip for Russian influence in the region. Over the years Russia has been able to reach effective agreements without collective decision-making, where it has a diplomatic disadvantage. By processing multiple agreements at the bilateral level, Russia was able to avoid pressure from the NATO alliance, and to successfully focus on differentiating the national interests of each Arctic state.

Similar to the argument put forward in the NATO and Security in the Arctic 2017 report, to effectively respond to Russia’s active role in the Arctic, NATO members must first unite in their alliance and solve their internal Arctic disputes. It should also be noted that the response of NATO members must be reciprocal but diplomatic, in order to respond with leverage and not to provoke further Russian activities in the Arctic. Deploying military or arctic assets risks encouraging further Russian militarization in the region, and could repel Moscow from the negotiating table, enable Russian pro-state media to invoke spread disinformation, and could further sharpen tensions within NATO. It is imperative that Arctic NATO members first solve their border disputes so that the focus can shift to developing a unified Arctic response to climate change, Russian Arctic activities, the establishment of new trade routes, and resource exploration.

Photo: Arctic territorial claims (2014) via Ministry of Foreign Affairs Denmark, Public Domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.