The current wave of right-wing populism in Europe is contributing to antidemocratic forms of governance in countries that de jure adhere to democratic principles. Similar to the Law and Justice Party (PiS) in Poland, Hungary’s Fidesz Party has implemented a series of undemocratic reforms contributing to an increase in corruption and failure to comply with the rule of law. Viktor Orbán’s leadership has transformed Hungary from one of the leading Central and Eastern European countries adapting to EU norms to one of its “worst performers.” Now scoring 44 out of 100 in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Hungary has experienced the steepest decline in the index’s measurement of that country’s fidelity to democratic values. In its 2021 Nations in Transit report, Freedom House has categorized Hungary as a “Transitional/Hybrid Regime.”

The Justice System

For over a decade, the Fidesz Party has worked to consolidate power over the Hungarian government’s executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The Hungarian justice system has been heavily affected by these reforms. In an effort to increase the number of judges who support values that align with those of the Fidesz Party, Orbán’s government passed laws that allowed it to appoint judges without the approval of the opposition and increased the number of judges on the Constitutional Court. These changes compromised the independence of the judiciary.

Two important institutions within the Hungarian justice system are the National Judiciary Office (NJO) and the National Judiciary Council (NJC). While the former serves as “the central administrative body of Hungarian courts,” the latter is a self-governing body for judges who are elected. Given the large scope of powers the NJO possesses, the NJC aims to maintain a balance of power within the NJO. However, a recent president of the NJO, Tünde Hando, challenged the legitimacy of the NJC, triggering a significant conflict between the two bodies in 2018-2019, preventing the NJC from serving its purpose. The NJO president enjoys “full administrative and also partial control over the courts.” Amnesty International criticized the aforementioned president for abuse of power and reported that the “President’s unbalanced powers in court administration continues to undermine the independence of the judiciary.” In addition, the Hungarian judiciary’s independence is negatively affected by the continuous attacks on independent media, leading “ordinary judges … [to take a step back from] freely expressing their opinion and stating their positions in matters related to the judiciary because of fear of retaliation.”

Repressive Policies: Media and LGBTQ+ Rights

Freedom of the press is one of the key elements of checks and balances in a democratic state, yet the Orbán Administration has curtailed it in Hungary during its ten-year rule. While the state owned 34% of the media when the Fidesz Party came to power in 2010, by the end of the decade that figure rose to 55%, an unprecedented high level since the communist regime. While Fidesz enjoys the support of almost 500 media outlets, its opponents are left in the dark, with only a few sympathetic outlets. The Polish and Serbian governments have followed this model of Hungarian media ownership. In Poland, PKN Orlen, a state-owned energy company, obtained control of 80% of that country’s media outlets and hinted at advertisement tax plans. In Serbia, the incumbent party has initiated and supported propaganda campaigns in support of the government through television and social media, contributing to an unrepresentative parliament in the elections of 2020.

While the Poles learned from the Hungarians about media control, the latter took inspiration from PiS’s approach to LGBT+ rights. Seeing Andrzej Duda’s success in the election of 2020 after engaging in a homophobic campaign, Orbán’s party increased its attacks on the LGBTQ+ community, denying the “legal recognition of transgender people and amending the constitution to ban adoption by same-sex couples.”

Corruption

The Hungarian government’s practices have resulted in an increase in corruption in that country. While more than two-thirds of Hungarians consider corruption to be a significant problem, citizens are faced with a fear of reporting these instances. Moreover, democratic recession is reflected in citizens’ reports that show that trust in government is quite low in regard to its handling of corruption, with 53% of respondents declaring that the “Hungarian government is tackling corruption badly.” Furthermore, the report shows that 50% of Hungarians believe that the level of corruption did not change over the past three years, while 32.9% report that it increased.

Undemocratic Shifts in Europe

Hungary constitutes another example of a former communist country that is stepping away from liberal democratic norms. As Francis Fukuyama notes, “what distinguishes a liberal democracy from an authoritarian regime is that it balances state power with institutional constraint – that is, the rule of law, and democratic accountability.” While it may be true that the PiS in Poland and the Fidesz in Hungary have secured the majority of the votes in the elections, it does not mean that their governments have the right to override independent institutions that play important roles in checks and balances, or curtail human rights. These undemocratic shifts in European countries – particularly related to constraints on judicial independence, freedom of the press and human rights – may serve as models that inspire neighbouring governments to fall under the same spell, with regional but also global implications.

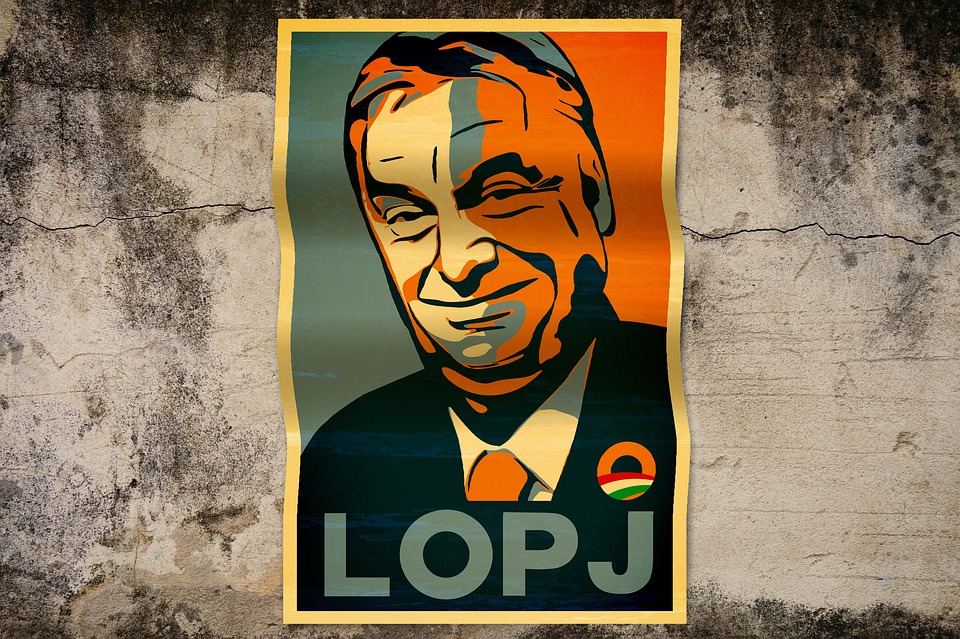

Photo: Wall Poster of Viktor Orbán, by tiburi via Pixabay. License.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.