The principle of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) has become a key part of humanitarian interventions since its entrenchment in the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Prior to the acceptance of the Responsibility to Protect, the international community acted on a case by case basis when deciding how to react to the violation of human rights. Like many other Western states have done since, the Canadian government responded to the policy challenge of violating state sovereignty through humanitarian interventions by adopting the concept of the Responsibility to Protect.

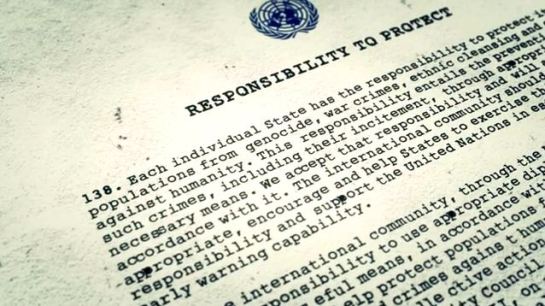

Since its inception, the principle of the R2P has gained momentum in multilateral operations that focus on humanitarian interventions. According to the United Nations, the concept of the Responsibility to Protect is based on the idea that “sovereignty no longer exclusively protects States from foreign interference; it is a charge of responsibility where states are accountable for the welfare of their people.” When a state fails to fulfill this responsibility, according to the principle of the R2P it is the role of the international community to ensure that populations are protected from genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing.

In order to ensure the protection of all populations from tyrannical governance, the R2P doctrine suggests that the international community be prepared to use the “appropriate diplomatic, humanitarian, and other means to protect populations from these crimes.” Collective action is a key part of this principle. Past humanitarian interventions have invoked this principle, with Libya being a key example.

With a growing shift toward NATO-led humanitarian interventions, the principles of the R2P doctrine are becoming a norm for collective action against a sovereign state. Especially for Canada, participating in NATO-led interventions has become the norm.

Despite the Canadian origins of the R2P, Prime Minister Harper has avoided using the term; instead he has preferred to focus on emphasizing Canada’s commitment to NATO. For example, during Operation Unified Protector in Libya, the Conservative government did not frame the mission in terms of the R2P. The Conservative government referred to Canada’s relationship with the United States, the UN, and NATO. Framing the issue in this way allowed the Conservative government to avoid terms that are typically branded as Liberal, for example terms originating under the Chrétien government. Indeed, the Responsibility to Protect was a key part of Lloyd Axworthy’s human security agenda, with his insistence that the “security of the state is not an end in itself.”

NATO is increasingly emphasizing the responsibility of its member states to uphold international peace and security beyond the North Atlantic area. The Canadian government should recognize that the principle of the Responsibility to Protect is a developing norm in the international community that has grown beyond its Canadian origins.

Such a shift might already be beginning. Just last week Jason Kenney, Canada’s Minister of Employment and Minister for Multiculturalism, stated in an emergency debate about Canada’s role in Iraq that the R2P dictates that Canada should act given its “moral obligation to defend human dignity.” Kenney’s statements were the subject of much confusion in the media, as the R2P had not been previously discussed.

While Kenney’s words conflict with the way in which the Conservative government has framed interventions in the past, in practise, it is likely that Canada’s actions abroad through NATO and otherwise will remain unchanged. In order for a state to intervene in another state under the R2P doctrine, a United Nations Security Council Resolution must first be passed. However, this has not yet happened for the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine, Syria, and Iraq. It is likely that Canada’s response to such a resolution would reflect its response to Resolutions 1970 and 1973 concerning Libya where there was marked participation, but no reference to the R2P. The way in which Canada frames its actions, however, may begin to shift if the Conservative government moves beyond the idea that avoiding terms such as the R2P makes little difference to its actions through NATO.