Canada is currently at a strategic crossroads, confronting an international environment that no longer allows middle powers to operate comfortably within a relatively stable, rules-based order. Great-power competition has returned in earnest, economic interdependence has become increasingly weaponized, and the long-standing assumption that allies will behave predictably has begun to erode. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Prime Minister Mark Carney captured this shift by describing this moment as a rupture rather than a transition, arguing that the international system must be understood “as it is” not as “we wish it to be.” His invocation of Finnish President Alexander Stubb’s idea of “values-based realism” reflects an uncomfortable and increasingly unavoidable reality in which power frequently overrides rules, and where even close partners are prepared to use economic leverage to shape outcomes to their liking.

This context is necessary for understanding Carney’s decision to re-engage China, following nearly a decade without a Canadian prime ministerial visit to Beijing. The move also raises the question of whether such engagement represents a pragmatic effort to recover strategic maneuverability in this more unstable system, or whether it risks undermining Canada’s credibility within NATO and Western security networks at a moment when alliance cohesion is already under strain. This is not simply a question of optics, as even limited engagement, if it is not anchored in a clear and disciplined strategy, can cause economic and security vulnerabilities.

During Carney’s visit, he and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed to a limited recalibration of trade relations that stopped short of a comprehensive free trade agreement but nonetheless reopened channels that had largely been frozen. Canada committed to reduce its previously prohibitive 100 per cent tariff on Chinese electric vehicles to an effective rate of roughly 6.1 per cent for a capped quota of approximately 49,000 vehicles per year, while Beijing agreed to cut its punitive tariffs on Canadian canola from around 85 per cent to roughly 15 per cent and to ease anti-discrimination duties on other agricultural and seafood exports.

Carney’s visit marks a departure from Canada’s recent China policy. Under the Trudeau government, Ottawa’s approach was most clearly articulated in the 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy, which described China as an “increasingly disruptive global power,” reflecting mounting concerns about Beijing’s foreign interference, coercive diplomacy, and human rights record, and also Canada’s close alignment with U.S. threat perceptions. Relations deteriorated sharply after Canada’s detention of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou and China’s retaliatory imprisonment of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, events that hardened Canadian attitudes toward China. This shift also translated into tighter investment screening under the Investment Canada Act, expanded research-security requirements for federally funded universities, and led to a growing emphasis on coordination with allies, especially the United States.

Canada’s economic integration with the United States has long been a defining feature of the bilateral relationship, but what has changed is not the degree of dependence so much as the reliability of the partner on which that dependence rests. Following the re-election of Donald Trump, American trade policy has become increasingly volatile and explicitly transactional. By 2024, roughly 75 per cent of Canadian exports were still destined for the United States, leaving Canada acutely exposed to shifts in American political and economic behaviour.

This imbalance helps explain Carney’s outreach to Beijing, which appears less an ideological pivot than an attempt to regain some measure of strategic leeway. Given that Carney himself once identified China as Canada’s most significant long-term security threat during his election campaign, the decision to re-engage China should not be read as a repudiation of that assessment, but rather as a hedge against over-reliance on a single partner whose behaviour has become increasingly unpredictable.

Hedging, however, is not neutral. It reflects an acknowledgement that risk cannot be eliminated, only managed, and that economic integration does not automatically produce mutual benefit. As Carney argued at Davos, countries cannot continue to operate within the fiction of “mutual benefit” when integration itself becomes a “source of subordination”. That reality was highlighted almost immediately. On January 24, U.S. President Donald Trump publicly signalled, in a post on his Truth Social platform, that the United States could impose tariffs of up to 100 per cent on Canadian goods should Ottawa move toward a formal free trade agreement with China. With the vast majority of Canadian exports flowing south, even the suggestion that access could be withdrawn highlights how economic integration has become a tool for disciplining allied policy autonomy.

However, Canada’s China policy cannot be evaluated in isolation because it intersects with NATO’s evolving assessment of China as a security actor. Since the 2019 London Declaration, the Alliance has increasingly treated China as a strategic concern, a shift formalised in NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept, which described China as a systemic challenge to Allied security, interests, and values, citing coercive policies, hybrid and cyber activity, disinformation, and Beijing’s deepening strategic partnership with Russia. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO has further linked China’s continued trade with Russia and its provision of dual-use materials and technologies to Moscow’s war effort, a position made explicit in the 2024 Washington Summit Declaration, which characterised China as a “decisive enabler” of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Within NATO strategic thinking, China represents a horizontal challenge, exerting pressure across multiple domains and complicating Allied deterrence even in the absence of direct military confrontation.

At the same time, NATO’s approach to China reflects uneven economic exposure across the Alliance. While the United States, United Kingdom, and some Nordic states have adopted more hawkish positions toward economic engagement with China, several European allies remain deeply tied to China through trade and investment. Major economies such as Germany, France, and Italy continue to balance risk concerns against substantial commercial exposure, while countries such as Greece and Hungary have maintained or expanded economic cooperation with China. Against this backdrop, it would not be unprecedented for Canada to pursue a selective and carefully managed economic relationship with China.

Despite this, Canada should remain attentive to the risks involved in economic engagement with China, which vary significantly across sectors. Regarding the lowering of tariffs on Chinese EVs, Ontario Premier Doug Ford expressed concern that this could raise surveillance and data-security risks, highlighting how trade in technologically integrated industries can create strategic exposure. On the other hand, other sectors present a different risk profile. Agricultural commodities such as canola, where Canada has already experienced Chinese trade coercion, show how trade dependence can be leveraged to impose political costs. Growing trade with China may, in theory, reduce dependence on the United States, but it can also introduce new vulnerabilities if poorly managed.

To conclude, Canada should pursue limited and conditional engagement with China not as a total diplomatic reset, but as a measured effort to expand Ottawa’s room for maneuver in a more coercive global economy by reopening select channels that reduce heavy reliance on the United States. Such engagement should remain confined to specific sectors, and include safeguards in sensitive areas such as electric vehicles and other technologically integrated imports. The overall aim should be to limit Canada’s exposure to coercion while remaining firmly anchored within the Western alliance system.

By Tasneem Gedi

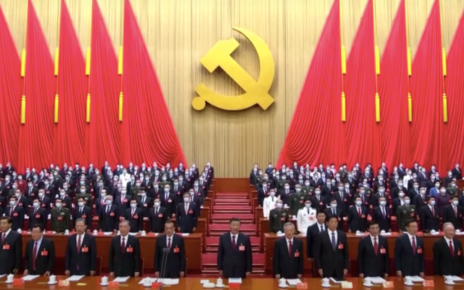

Photo: Xi Jingping 02, uploaded on April 13, 2024 by Trong Khiem Nguyen. Public domain image accessed via Flickr.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.