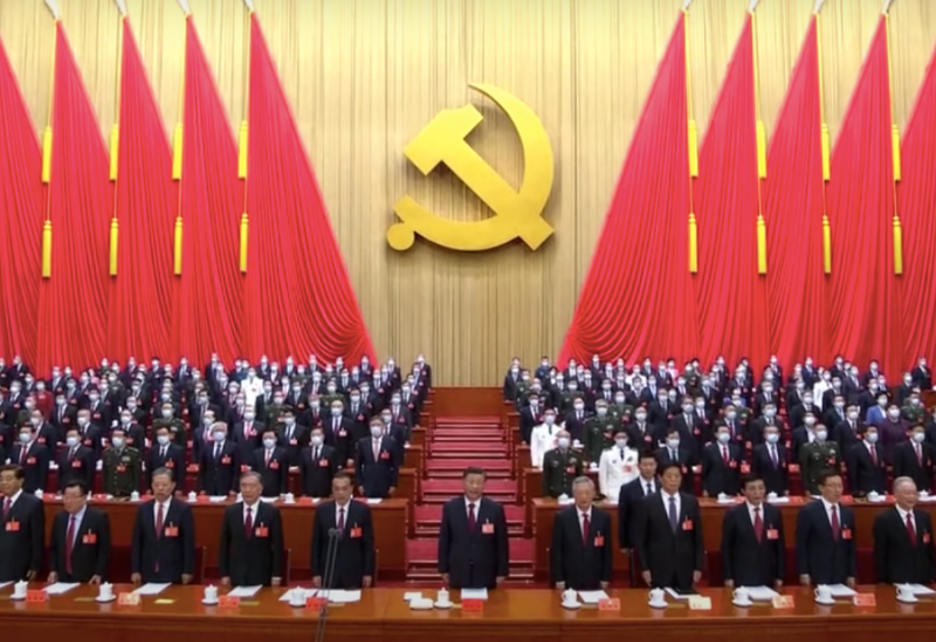

One of the most enduring images from the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Congress in October was the physical and public removal of Xi Jinping’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, from the conference. This spectacle was a clear signal to the Chinese people that they are now in the Xi Jinping era. What does this mean for Canadians? There has been a lot of friction between Canada and China under Xi’s reign, and signals from the 20th Congress indicate that this tension will likely continue to build in the five years until China’s next Party Congress.

Under President Xi Jinping, China has been more willing to aggressively further its economic and territorial ambitions, causing concern for Canada. In 2018, Canada faced confrontations with China over the detention of each other’s citizens. The Chief Financial Officer of the Chinese telecommunications company Huawei, Meng Wanzhou, was arrested in Vancouver at the request of the US. China retaliated against this by detaining three Canadian nationals – the “Two Michaels” as well as Robert Schellenberg who is still being held on drug charges.

Canada and other Western nations have also witnessed greater Chinese territorial aggression under President Xi. Of particular concern is Beijing’s claim to territory in the South China Sea known as the nine-dash lines. This is the name given to the boundary which Beijing holds to be territorial sovereign waters, regardless of established borders of other nations in the region, violating the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea that governs how territorial waters are to be defined and treated internationally. Due to Ottawa’s concern over Beijing’s policy in the South China Sea, Canada created Operation NEON in 2019 to ward off aggression in the Indo-Pacific. In October, the Canadian Navy concluded an exercise in the region with the Japanese and US navies, demonstrating interoperability between the allied navies and their mutual commitment to peace.

Canada is also unsettled by the potential threat China poses to its territorial sovereignty in the Arctic. China, under Xi, has declared itself a ‘Near-Arctic Power’ and, in its 2018 Arctic policy White Paper, outlined its goal of participating in Arctic governance. Finally, Canada has also been in conflict with China over its ongoing persecution and detention of its Muslim minority population: the Uyghurs. In 2021, Canada’s Parliament officially declared Beijing’s treatment of Uyghurs to be genocide, an act that increased the hostility even further between the two counties.

So, what about the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Congress should cause Canadians to think these tensions might increase to an even greater extent? First, all Party Congress reports to date have referred to “peace and development” with respect to its external environment. However, in Xi’s 2022 report, this language was omitted and replaced by terms such as “preparing for the storm” and a declaration that China’s national rejuvenation would be based on maintaining national security. Xi went on to say that China’s defense budget would be doubled to US $230 billion in order to accelerate military modernization and the production of aircraft carriers. Second, Xi Jinping stated that China would be moving forward with its absorption of Taiwan, aiming to annex the country by 2027 rather than its previously set goal of 2049.

Equally concerning is that Xi Jinping seems to be removing checks and balances to his power. In 2018, Xi boldly removed presidential term limits in China. At the 20th Party Congress, he unveiled his new leadership team, making it clear that he had appointed officials who, above all else, would be unwaveringly loyal to Xi – further centralizing his power by eliminating internal voices of dissent. The most notable example of this is the promotion of Li Qiang to the position of Premier. Li is the party official who oversaw the COVID lockdown in Shanghai, a policy that led to significant food shortages and economic stagnation. He Lifeng, an economist who is a proponent of Xi’s policy of a centrally planned economy, has also been promoted to the position of Vice Premier for economic affairs. While head of China’s National Development and Reform Commission, He Lifeng oversaw the recent centralisation of economic planning for the country at the highest level. His appointment will dissuade bureaucrats from pushing for more decentralized or market oriented economic policy. Given the slate of officials Xi Jinping has promoted, it is expected that his preferred policies will meet little resistance from the Chinese Communist Party.

In November 2022, Canadian Foreign Minister Melanie Joly announced that Canada would be releasing a long awaited Indo-Pacific strategy in December and warned that, “the China of 1970 is not the China today.” Citing Canada’s recent efforts to lessen economic ties with China, Joly was clear in stating that Ottawa must be “clear-eyed” when dealing with Beijing and urging Canadians to guard against naivety about China’s ambitions. The Foreign Minister identified where Canada’s efforts should be focused: increasing support of Taiwan, increasing Canada’s trade relations with India, and further distancing Ottawa’s economic relationship with Beijing. Joly’s statement recognizes the appetite for a Canadian foreign policy that aligns with Washington’s stance on US-China relations, while keeping in mind Canadians’ aversion to increased defense spending.

From Canada’s perspective, there are many reasons to fear increased tensions between the two countries. In the long term, Xi’s territorial ambitions could impact the Canadian Arctic. Friction is also certain to arise in the South China Sea where Canada has maritime involvement. In this year’s 20th Party Congress, it became clear that Xi Jinping still reigns supreme in China. Given the conflict Canada has had with China while President Xi has been in power, it is justified in fearing increased friction between the two countries and creating a new Indo-Pacific strategy to mitigate threats China poses to Canada. In fact, the recent altercation between Xi Jinping and Justin Trudeau over supposed leaks to the media at the G-20 meetings points in this direction.

Photo: Participants standing during the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Congress, October 16, 2022, by China News Service via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 3.0. The image has been cropped and the size has been reformatted for this website.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.