Hybrid warfare combines regular military power with irregular methods such as disinformation, cyberattacks, and economic coercion. As defined by NATO, hybrid methods aim to erode trust in institutions and information sources, complicating the public’s ability to know whether a conflict is even taking place. Hybrid operations have the potential to destabilize, weaken and even defeat a nation without outright war or even military action.

Women are disproportionately affected by these operations. Hybrid actors often exploit gender stereotypes and use online platforms to spread disinformation targeting women, such as false narratives about their roles or influence in society. These narratives undermine women’s credibility, raising doubt about their expertise, leadership, or public statements. This, in turn, weakens public trust in institutions and harms democratic resilience.

Gendered disinformation is one of the most damaging tactics. It is false or manipulated information designed to exploit gender-based stereotypes. Recent research from the Centre for International and Defence Policy at Queen’s University exposed how such disinformation portrays women as overly emotional, incompetent, or unqualified leaders. These narratives are created intentionally by hybrid actors, such as Russia, to reduce public trust in women in positions of influence and to divide societies. When women leaders are discredited through gendered disinformation, the public may lose confidence in the institutions they lead, putting the political systems of their countries at risk.

In addition to disinformation, there are other hybrid threats, which include coordinated information operations. NATO defines these as “intentional, malicious, manipulative, and coordinated activities that state or non-state actors would undertake… to undermine and divide NATO, its Allies and partners.” These frequently involve propaganda, targeted messaging, and coordinated political movements. In fact, NATO notes that some of these operations manipulate “gender narratives … to hinder division and destabilize societies.” In other words, hybrid war not only operates in a traditionally physical or destructive manner; it also works to manipulate perceptions of gender, leadership, and trust.

Another aspect of this threat is technology-facilitated violence against women and girls (TF-VAWG). This includes activities such as cyberstalking, online harassment, doxxing (putting “private” information into the public domain), and digitally manipulated images used to intimidate or shame women and girls. UN Women reports that between 16% and 58% of women have encountered this sort of digital abuse. This sort of violence does not solely impact the individual. It deters women from speaking up, showing up in public life in their communities or taking up positions of leadership. When women are attacked in public spaces, it shrinks diversity in public organizations as well as democratic participation.

Impact can be more powerful when hybrid actors combine cyberattacks with gendered narratives. For example, actors could carry out cyberattacks on critical infrastructure while simultaneously advancing false claims or scandals concerning female officials. The amplified impact of this dual front targets fear and spreads doubt as a more effective tactic than either approach alone. Therefore, while NATO’s hybrid threat strategy already includes economic and information countermeasures, these efforts should include an analysis of gendered attacks to be fully effective.

Economic pressure is another element of hybrid warfare that disproportionately affects women. Adversaries regularly disrupt social services or disrupt essential infrastructure, such as transport or healthcare, thus resulting in a negative impact on women. Since women often manage household and caregiving responsibilities, when these systems stall or weaken, women’s ability to participate in both public and political life is limited, furthering social inequality. Hybrid actors build on and magnify social fractures by targeting economic vulnerabilities. Often, societies that use hybrid tactics apply this pressure in a way that hits women harder than men.

To address gendered hybrid threats, NATO does have a policy structure. In its Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda, NATO declares that gendered perspectives should be integrated into all of NATO’s work (including crisis management, defence, and communications) in peacetime and wartime. By incorporating technology-facilitated violence and information operations into that policy, NATO is indicating that hybrid gendered threats are not an afterthought, but a core security issue.

To enhance resilience, NATO allies should establish a gendered analysis teams that research how different hybrid actors impact women and men differently. These intelligence and security teams should also require training to understand where gender-specific impacts fit with the broader aspects of hybrid operations. If analysts knew how disinformation campaigns seek to exploit gender norms, they could develop early warning systems to detect emerging disinformation trends and actions that could potentially stop false gendered narratives from becoming entrenched.

Alongside these analysis teams, another practical approach is to create a dedicated gender-focused information resilience hubs within NATO, which differs from the analysis team by providing operational monitoring and real-time response rather than research and training. These hubs could utilize open-source intelligence and data analysis to identify active disinformation networks in real-time, spot trends in gendered messaging, and support coordination among countries. By establishing this capability, NATO members can preemptively disrupt hybrid campaigns and better protect its member states’ societies.

It is also crucial to support women who have suffered digital violence. NATO and Allies can implement, or support, rapid response mechanisms that provide legal advice, psychological support, or even technical assistance to victims of online abuse. The availability of comprehensive support for women can mitigate the negative effects of harassment on women’s participation in public and political life.

Finally, public education is important. NATO can work with civil society organizations and governments to encourage media literacy programs for the general public that emphasize the concept of hybrid warfare and particularly gendered disinformation campaigns to the citizen users, so that citizens are able to observe how these narratives are pushed, as well as used strategically.

Hybrid warfare is dangerous, not just to physical safety but also to trust, participation, and cohesion among people. Each time women are discredited, harassed, or exiled from public life, the institutions that safeguard democracy are made more fragile. Integrating gender into NATO’s analysis of hybrid warfare, as well as their support systems, public messaging, and planning around it, protects not only women; it protects everyone in the alliance.

In short, hybrid rival actors utilize gender as part of their warfare toolkit. To respond to these threats, NATO must organize gender in its core priorities and decision-making processes, not simply as a diverging question, but as a fundamental necessity. This will help the NATO alliance protect individual rights and collective security.

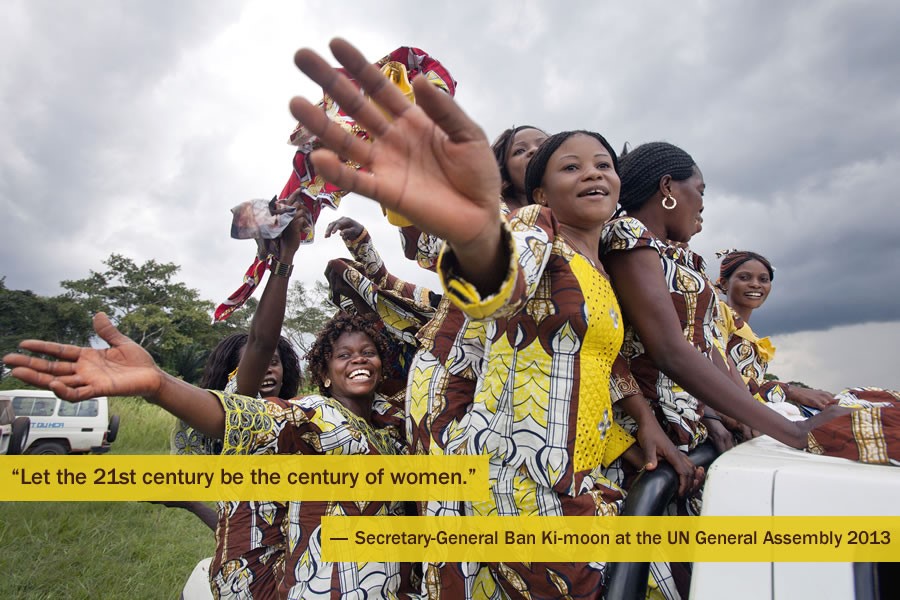

Photo: Regional Conference on Gender Disinformation and Ethical Media Coverage – Tbilisi – WECF. (2022, December 26). WECF.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.