The book Petrostate by Marshall I. Goldman illustrates Russia’s dominant role in the international energy market. In his book, Goldman shares his experience of visiting Gazprom, Russia’s largest state-owned energy firm. He is awed by the scale of the buildings and the operations that control all pipelines that stretch from East Siberia to the heart of Europe. Of course, the book is not his travelogue of Russian energy firms. The book is Marshall’s expressing his concerns about Europe’s becoming overly dependent on Russian energy. The web of pipeline network Goldman describes in the introduction has been the woe of Europe due to the crisis in Ukraine. European countries that are in an uncomfortable relationship with Russia or Ukraine especially have been facing challenges in securing sufficient energy supply for the winter.

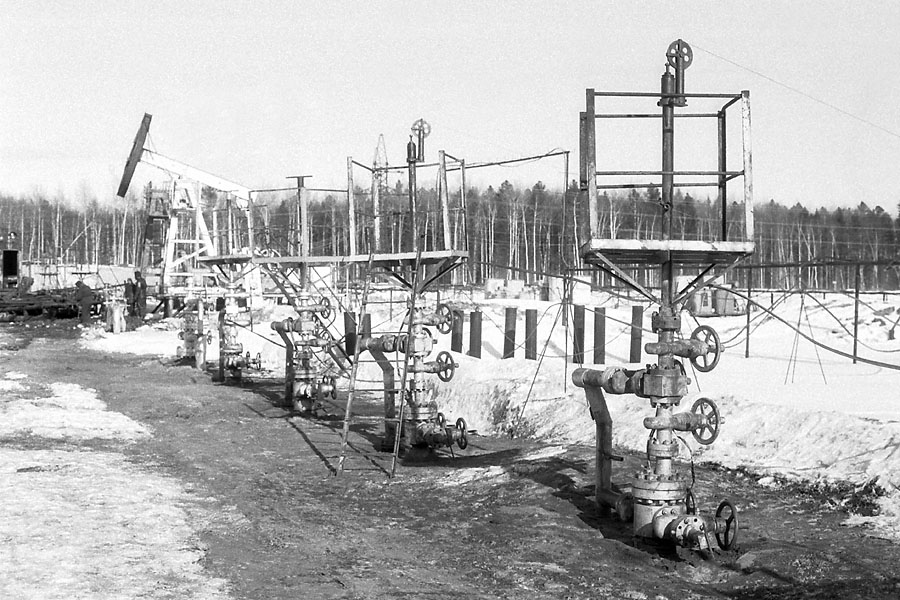

While Russia can attempt to intimidate its disgruntled neighbors with threats to raise the energy costs or by simply shutting down the pipeline, the overdependence on oil for revenue has made Russia vulnerable to any fluctuation in the energy sector. Goldman describes Russia as a “victim” of Dutch disease—the phenomenon of overreliance on oil revenue that often ends up killing the country’s manufacturing sector. The country continues to rely on the Soviet-era technologies except in a few specialized sectors such as defense manufacturing. The losses from the inefficient technologies have been managed from the revenue generated by the oil sector.

Lately, Russia has been suffering from the drop in oil price. As a state that heavily depends on revenue from oil, the falling oil price has inflicted a devastating impact on the Russian economy. Due to the sanctions imposed on Russia for destabilizing Ukraine, the value of ruble has been in free-fall for some time. There are now estimates that Russian GDP will contract from between 3 to 6 percent in 2015. The drop in oil revenue has brewed troubles for Russia’s dysfunctional domestic economy that has heavily relied on oil to fund social programs and assist domestic firms with less than adequate productivity.

It is no surprise that some are predicting the collapse of Russia’s economy because a similar phenomenon occurred in the 1980s. Goldman explains, the Soviet Union could depend on its European customers as a reliable source of income because they grew tired of overreliance on Middle East energy after the Oil Shocks. But for the Soviet Union, the problem remained. The oil and gas were the only exportable goods that could be exchanged for foreign currency required for purchasing technologies that the Soviet Union could not produce on its own. Troubles began when the undeveloped oil reserves in the North Sea and West Siberia was tapped, while Saudi Arabia started pumping more oil. The overproduction brought down the average oil price in 1986 to $25.63—a half of what it had been the year before. Ultimately, the Soviet Union could not overcome this insurmountable economic challenge as it could not generate enough foreign currency to purchase implements required for sustaining the oil production.

Envisaging Russia’s poor economic performance in the upcoming year with the assessment of the consequences in the 1980s, may be imprudent as there are suggestions that the oil price will quickly begin to rise as soon as 2016. An article featured in Russia Direct suggests that there are factors that can still raise the price. Despite the slowdown of the Chinese economy and the overproduction of oil, the OPEC states cannot afford to sell oil at such a low price for an indefinite period, because the majority of OPEC members are heavily dependent on oil revenue. For instance, 90% of Saudi Arabia’s budget is dependent on oil.

An increase in oil price would strengthen Russian leadership’s belief that Russia would be able to weather the storm of economic sanctions. A leap in oil price is, therefore, a double-edged sword. Some of the oil-producing Western countries would be happy as they can rely more on their own oil sector for increasing employment and creating more revenue. However, it can also increase Russian leadership’s confidence and encourage Russia to become more active in fueling the instability in Donbass. Therefore, we can only hope that a low energy price would force Russia to raise a white flag.