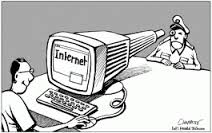

The proliferation of the internet over the past two decades has had a profound impact on the way we now interact with each other. This global reach allows us to engage with a massive audience by conveying our thoughts and discussing a variety of social issues. Coinciding with the rise of the internet though has been the rise of those who wish to manage and limit its scope, particularly those parties who feel threatened by information and opinions which may challenge their own views. Despite the United Nations that declaring internet freedom is a basic human right, repressive regimes still seek to limit the content their citizens can access.

Understandably, there are reasonable limits to what we are free to express on the internet. In order to protect vulnerable people and limit violence and harassment, there is widespread support for censoring child pornography and hate speech that may be posted online. To this extent, many states engage in some form of internet censorship. However the real problem lies in the filtering of content that may contradict the political, social, or religious values of a state. According to the Open Net Initiative, this type of filtering is pervasive in many of the world’s most populous regions, including North Africa and the Middle East, Central Asia, and in some East Asian states. Interestingly, while extensive content filtering is denounced by many Western states, Canadian and American technology companies have recently been implicated in providing foreign governments with software that is being used to restrict internet access.

Netsweeper, a Canadian software company based out of Guelph, Ontario, came under fire in 2011 after Citizen Lab, an internet freedom watchdog at the University of Toronto, alleged that Netsweeper was selling its web filtering technology to state-owned telecommunications companies in Qatar, the UAE, and Kuwait. According the Citizen Lab, Netsweeper’s software was being used by these clients to restrict access to political, religious, and homosexual internet content that supposedly undermines traditional state values. More recently, Netsweeper has also been accused of selling its products to Pakistan to filter the same kind of content, as well as providing software to Somalia that is being used to filter pornographic content and websites that offer tools for protecting anonymity.

Interestingly enough, Netsweeper is not actually engaging in any illegal business practices. Canadian companies are not responsible for the way their products are used by the purchaser, so Netsweeper can continue to sell its products to repressive regimes without facing any legal recourse. Nevertheless, Netsweeper can be accused of conducting business in a highly unethical manner. The human rights records of many of Netsweeper’s government clients are dismal, and Netsweeper could not possibly be so naive as to believe that its products are not being used to filter social, political, and religious content. Despite the morally ambiguous nature of Netsweeper’s business practices, apart from increasing media exposure and societal pressure there are few mechanisms in place to prevent or even discourage such companies from doing business with repressive governments. Considering that many authoritarian regimes are attempting to greatly restrict internet access in their states, there is a significant demand for filtering technology and providing it can be a potentially lucrative opportunity. From a strictly economic perspective, there are few reasons not to sell to repressive governments.

As with almost any other product, it is reasonable to assume that some parties who purchase filtering software may use that technology in an unethical way. Netsweeper is not an anomaly in the tech industry, and a number of IT giants including McAfee and Cisco Systems have been criticized for selling their products to governments with questionable human rights records. And while the products of some tech companies are used to suppress human rights, it is highly unlikely that they support the actions of the regimes they deal with. These companies may be selling their products under the impression that they will be used for legitimate purposes, such as the filtering of child pornography or hate speech. The dilemma is whether or not it is possible, or even fair, for Western governments to regulate to whom tech companies can sell their products. The intent may be to provide a legitimate service for filtering harmful content, but instead the product is being misused in an entirely different and antithetical way. If this is the case, is it right for Western governments to dictate who software companies can sell to on the basis of ethics?

In the past decade, there have been some attempts by US lawmakers to regulate software exports in order to better protect human rights abroad. The Global Online Freedom Act, first introduced in 2006 but reintroduced in 2013, has been making its way through the various subcommittees in the House of Representatives. The Bill seeks to compel software-exporting companies to comply with human rights standards by providing annual reports and will attempt to limit their involvement with internet-restricting states by prohibiting the export of internet-filtering technology to those countries.

Though in its infancy, the Global Online Freedom Act is an interesting approach to dealing with the controversy between economics and ethics. Though such measures may have some economic detriments and software companies may lose out on lucrative business opportunities, the social and political dividends of ensuring open access to the internet abroad has the potential to greatly outweigh these costs. Freedom of speech is imperative to creating an articulate and informed society, which in turn advances human rights and democratic values, ideals heavily espoused by the West. However, such measures run the risk of unjustly burdening the tech industry with increased regulations for the nefarious actions of their clients, which they have no control over. Striking the right balance between respect for human rights and just treatment of corporate actors is an arduous task, but considering the proliferation of the internet over the past two decades and its prominence as a global platform for free speech, the debate over internet censorship has significant economic, political, and social consequences.