With just weeks to go before it is set to stage the 2014 World Cup, Brazil, is attracting global attention due to widespread protests and strikes across the tournament’s 12 host cities. The demonstrations have included labour groups, police officers, teachers, transport workers, public employees, activists and the homeless, with participants calling for better living and working conditions. Despite being awarded the tournament in 2007, Brazil has yet to complete all of the 12 stadiums for the competition, which critics claim is a sign of both corruption and incompetence.

The protests mark the second successive year Brazilians have taken to the streets. Over one million Brazilians protested raises in public transportation fares, corruption and poor health services while Brazil hosted last year’s Confederations Cup, a warm-up tournament held prior to each World Cup.

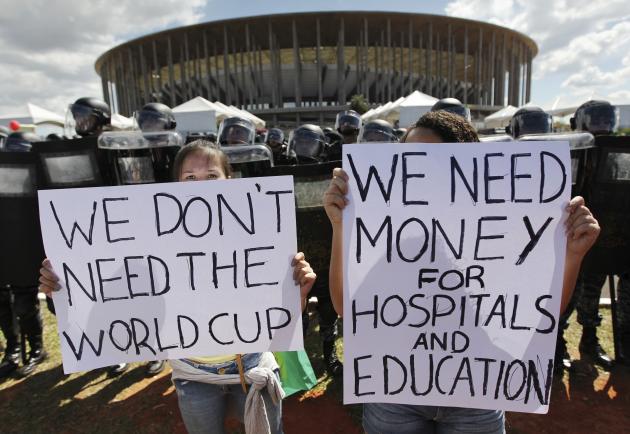

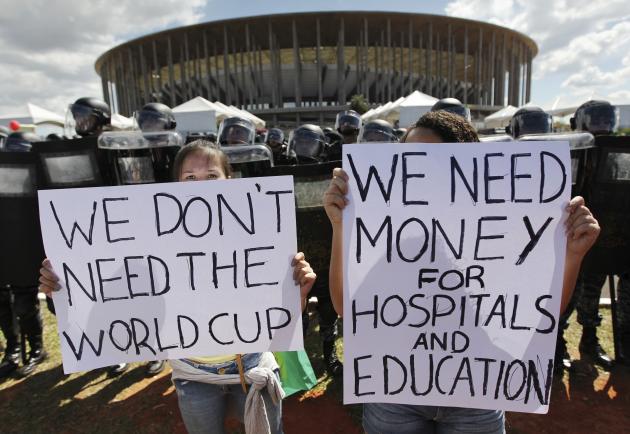

Among the concerns raised by locals against hosting this year’s World Cup are wasteful spending, corruption, and fears the tournament will not serve Brazil’s overall good. Brazilian civil society organizations decry the amount of money spent on the tournament, saying it should have been spent instead on alleviating poverty. For example, a recent audit found the new World Cup stadium built in Brasilia has cost USD$900 million of public money of which $275 million was fraudulently billed. Similarly, the total cost of Brazil’s 12 World Cup stadiums is $4.2 billion, four times more than they were expected to cost when Brazil won the tournament’s hosting rights in 2007.

The entire cost of the tournament is set to cost the country a stunning $11 billion. In comparison, Germany (2006) and South Africa (2010) spent about $5 billion and $3.5 billion respectively to host the tournament. With 3.7 million tourists set to visit during the one-month event, Brazilian officials are claiming hosting the World Cup will yield ‘economic and social returns’ and that the tournament will net Brazil $3 billion. However most of the 37 million Brazilians living in poverty (out of a total population of nearly 200 million) are unlikely to gain financially from the tournament. Further, only 300,000 jobs are expected to be created from the event, a far cry from the 3.6 million announced by the government in 2010.

Evidence strongly suggests domestic support for hosting the tournament has waned significantly. In 2008, 79% of those polled supported the World Cup in Brazil compared to just 48% support in April of this year. Perhaps an even more stunning figure is the 45% of Brazilians who in a recent survey stated they did not want Brazil to win the tournament. Such low support is stunning in the soccer-mad Brazil, which is the World Cup’s most accomplished nation, having won the tournament a record five times.

The waning public support is likely due to a combination of the aforementioned issues, including poor organization, failed promises, corruption allegations and exorbitant costs of hosting the event. Protesters have expressed the desire to ‘teach politicians a lesson’ and lament what they perceive as misplaced priorities.

With presidential elections set to be held in October, incumbent Dilma Rousseff, has seen her support slip, however at the moment she remains the front runner to win the vote. Her decline in popularity can be explained by factors including stagnating economic growth and inflation, which she responded to at the beginning of May by pledging to cut taxes, increase minimum wage and spending for the poor.

The timing of the elections has led some to opine the upcoming tournament will not only determine the World Cup winner, but also the country’s president in October. Though this claim is somewhat of a stretch, the success or failure of the tournament will likely influence public perception of Rousseff and her government.

The argument can also be made that Rousseff’s success in October may be linked to Brazil’s placing in the World Cup. Despite growing opposition to hosting the tournament, we can likely expect to see public dissent ease once the tournament commences as Brazilians closely follow their national team. Always among the pre-tournament favourites, the Brazilian national team will be entering the tournament with an in-form side and despite what the opinion polls say, will have nearly all of the country’s 200 million inhabitants supporting them. If Brazil adds a sixth World Cup trophy to its collection, one can expect to see Brazilians temporarily set their political grievances aside. A Brazil win will likely reduce the number of questions asked about the prudence of hosting the event.

Conversely, failure to win the 2014 World Cup will likely further add fuel to domestic criticism of the tournament and may even lead fans to blame the government for failing to create an atmosphere conducive to a Brazil win. Though it is difficult to predict where things will be heading in Brazil in the coming weeks and months, odds are Brazil’s outcome on the pitch will have some political implications leading up to the October presidential vote.