After 70 years of construction and maintenance, the organizational hierarchies of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) seem established, entrenched, and eternal. Yet, in a twist of irony, NATO has seemingly fallen victim to its own success – with the Soviet threat vanquished in 1991 and the memory of the Cold War rapidly fading, the publics of NATO’s 29 member-states largely take today’s hard-fought peace for granted.

That peace, a result of NATO’s structural integrity, is an abnormal one in the scope of human history. NATO is the longest standing defensive alliance ever, and has expanded its membership as recently as 2017. While its original mission has been fulfilled in deterring Soviet aggression, NATO’s modern existence and operation is more than an institutional hangover from bygone days. With a resurgent Russia making moves in the Sea of Azov, and NATO’s new focus on counterinsurgency and international peacemaking, the alliance’s shifting role across the Atlantic – and Canada’s role within the alliance – is as relevant as it was at the time of its 1949 inception.

NATO’s contemporary structure reflects the ideals of ‘Atlanticism’, or ‘Transatlanticism’; a notion that there are deep civilizational, cultural, and political ties that bind together the people and nations of Europe and those of North America. These twin-destinies will, in theory, form the nexus of global stability by ensuring the inalienable security of the Atlantic zone, and therefore guarantee peaceable commerce and the proliferation of democratic thought therein. When NATO leaders convene in the Brussels headquarters each year, they do so around a circular – or rather, oblong – table, representing the nominal equality of each member in relation to the others. As simple and natural as this arrangement appears, it was not, however, an inevitable one. Indeed, there was much initial dispute about what NATO would look like in application, even after surpassing the hurdle that was getting its founders to agree upon its necessity in the first place.

After the end of the Second World War, American strategists knew that a perpetual commitment to the reconstitution of war-torn Europe bore with it an associated set of political risks, especially when presented before a U.S Senate that was habitually prone to bouts of isolationism. In response to these fears, George Kennan, high-ranking diplomat and author of the 1947 ‘Containment’ doctrine, was one of the first to advocate for the ‘Twin-Pillar’, or ‘Dumbbell’ concept of NATO.

This model advances the existence of two strategic ‘pillars’ or ‘weights’ that would exist at either end of a transatlantic dumbbell, connected by a consultory linkage between the two. One such pillar would be formed by the Western Europeans, and the other would be comprised of the North Americans – that is, Canada and the United States. In Kennan’s theory, the sheer weight of American hegemony would roughly ensure equality between the twin-pillars, and in doing so the dumbbell of the alliance was meant to achieve balance and effectiveness. Western European leaders would be free to independently assess their security needs, and after negotiation, the Americans and Canadians would gracefully come to their aid. Yet, evidently, the contemporary NATO looks nothing like the vaunted dumbbell. So why did this continental model never come to fruition?

European leaders fretted that an American end of the dumbbell meant the U.S military would be stationed in North America, separated from Europe by the vast expanses of the Atlantic Ocean, and therefore distant from the frontlines of the Soviet menace in Germany. In the event of a Soviet invasion, the Europeans needed to know that the Americans had an unwavering and personal stake in joint protection.

Even on the North American end, Canada vehemently dissented to the idea of the dumbbell, viewing the notion of a ‘North American’ community as one imposed on them by European aspirations and conceptualizations of their own polities. If Ottawa had to share decision-making responsibility with Washington, it would inevitably be crowded out in any discussions to be had with Brussels, and the Canadian perspective would invariably be lost. For these reasons, Canada viewed it as necessary that NATO would not be the result of bicontinental cooperation, but rather the synthesis of each member-states’ commitments to every other member-state within the alliance.

The Canadian view of collective security ultimately won out in 1949, and has informed the shape and structure of NATO today – but Canada’s fears of the dumbbell are not entirely dead and buried yet. Should the process of European integration take on an armed “security and defence identity” that provides for its own self-defence on the continent, then Canada, as the only “mid-size non-European member”, could suffer a heavily reduced role in future NATO negotiations. The natural gravities of an armed European project on the one end, with the continued predominance of the United States on the other, might yet find Canada the loser in any potential reversion to the ‘Dumbbell’ schematic of NATO.

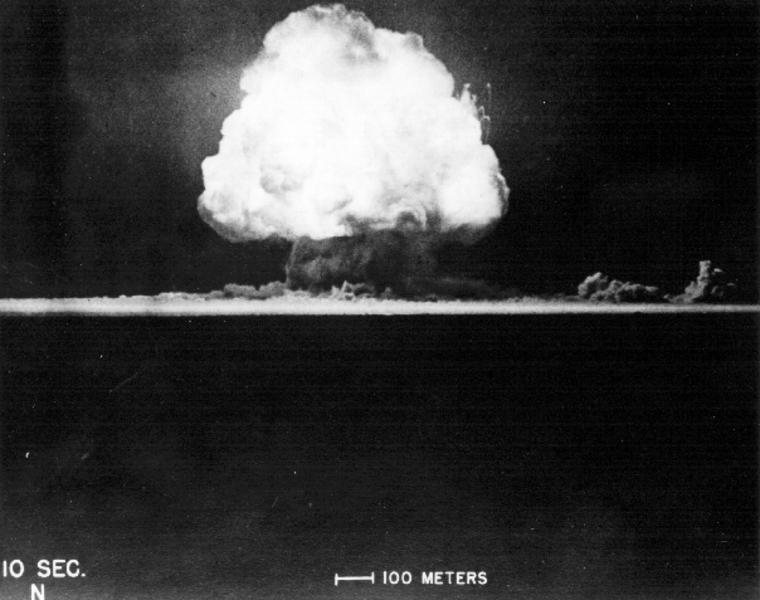

Featured Image: Visualizing the two ends of NATO’s dumbbell – one in North America and the other in Europe. Graphic produced internally.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.