On September 28, 2014 New York City’s famous Madison Square Garden was packed to its seams. What attracted such large crowds on this sunny Sunday was not a gyrating pop star or a nail biting Knicks game, but rather the attendance of the diminutive, teetotaller Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. His official two day visit to the United States, which included his superstar reception in New York, not only reinvigorated America-Indian relations, but also shed light on the growing political influence of Indian Americans who played a critical role in making Modi’s visit rather unprecedented in the long line of official state visits that have graced the United States.

Naturally, this event had an impact on American foreign policy, but the influence of an ethnic group having influence on a nation’s foreign policy is nothing new for the United States. As a nation that is largely built by immigration, it is of no surprise that the understanding of American foreign policy must include a comprehension of the motivations and aspirations of each ethnic group that composes the American melting pot. For instance, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, it was of American interest to maintain a favourable relationship with the hegemon of the time, Great Britain, which helped secure the world’s sea lanes for the benefit American exports.

However, American politicians often irked Britain with talk of Irish independence and, even more scandalous, American authorities were known to turn a blind eye to the shipment of arms to Irish rebels fighting against the British Crown.

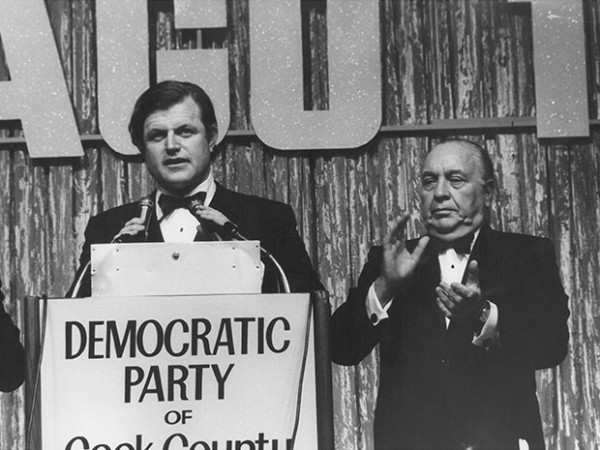

Much of this contradictory approach was primarily due to the massive Irish American diaspora, who not only wielded political power through their high-level positions within the government, labour unions, and the Roman Catholic Church but who also felt that their adopted land should do more to help free their ancestral home. Similar exercise of political power can be witnessed in the Jewish – and Cuban -American communities, which have followed the Irish example by converting their local political clout into a major influence on American foreign policy.

The American immigrant experience of forging their own interest within the foreign policy of their adopted home has also been played out in Canada. For instance, the recently belligerent actions by Russia towards Ukraine have elicited strong disapproval in Western countries. However, in relation to its fellow Western allies, Canada has been the loudest of voices when it comes to condemning Russian aggression and has lobbied heavily for the international community to implement sanctions against the Russian economy. Such fierce opposition may be the result of the large and long established Ukrainian-Canadian community, which numbers in the millions.

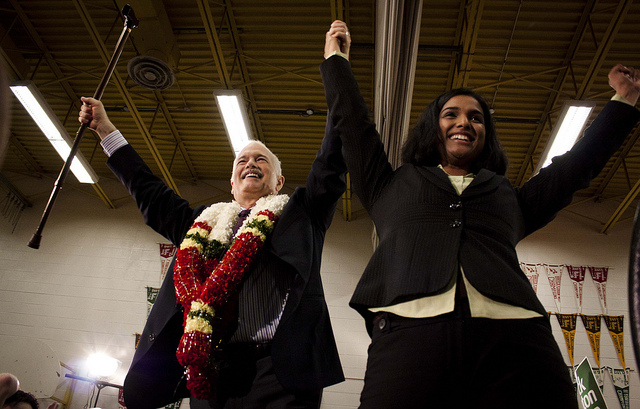

Furthermore, relatively smaller and more recently arrived immigrant groups are also beginning to exercise their political influence for the purpose of achieving their respective international goals. One interesting example is the Tamil Canadian community, which, like its Irish counterpart in the United States, has sought to integrate within their adopted home by electing officials of Tamil descent into positions in Canada. Due to the fact that the Tamil community consists largely of refugees who fled the discrimination, persecution and war that made Sri Lanka, their former home, intolerable to live in, it will be only natural that Tamils will have a powerful voice when it comes to Canada’s relationship with Sri Lanka. Already, with the election of the first Tamil Canadian Member of Parliament, Rathika Sitsabeasan and the possibility of more Tamil Canadians being elected to Parliament in the next election, the Canadian government, particularly the ruling Conservative party, has turned 180 degrees in its relation with Sri Lanka.

Once considered a supporter of the Sri Lankan government, the Harper Conservative government took the unprecedented step of refusing funding for the Commonwealth Secretariat meeting in Sri Lanka over the alleged human rights abuses that the Sri Lankan government inflicted on the country’s Tamil minority. Some cynics, particularly those in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy circles, consider the change in policy by the Canadian Conservatives as a means to tap into to the growing clout exerted by a rather close knit and politically ambitious Tamil Canadian community.

For some well-organized ethnic groups exerting influence over a nation’s foreign policy is a major cause of concern as they see special interests trumping the nation’s interests at large. One need only look at the controversial book, The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy by Stephen Walt and John J. Mearsheimer, which suggests, through the example of the Israeli-American relationship, that serving the interests of a particular ethnic group hurts the overall foreign policy goals of a nation. The same criticism was expressed after Harper refused to attend the Commonwealth Summit in Sri Lanka.

Conversely, though, when it comes to pluralistic democratic nations like the United States and Canada, the foreign policy, like the domestic policy, will, on the basis of democracy, be subjected to the varied interests and concerns of the electorate. If a segment of the electorate has a relatively greater stake in events happening abroad, it is within their democratic rights to express their concerns and expect their government to act accordingly as long as it is within legal limits. In other words, the national interests of a democratic state are dictated by the interests of the electorate, no matter who they are. Anojan Nicholas