Two extremely important events for Turkey’s energy policy took place within days of each other at the end of May and in early June. The first was the formal opening of the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC). The second was the order, by Dutch courts, that Gazprom’s assets in The Netherlands should be frozen.

That court order was rendered in forfeit for Gazprom’s failure to honour the ruling in March, by the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, that it owes US$2.6 billion to Ukraine’s Naftogaz, for failure to fulfill supply contracts and underpayment of transited gas.

The combination of these two outstanding events decreases the chances the TurkStream 2 project will be successfully implemented, and increases the chances of the further expansion of the SGC to the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea.

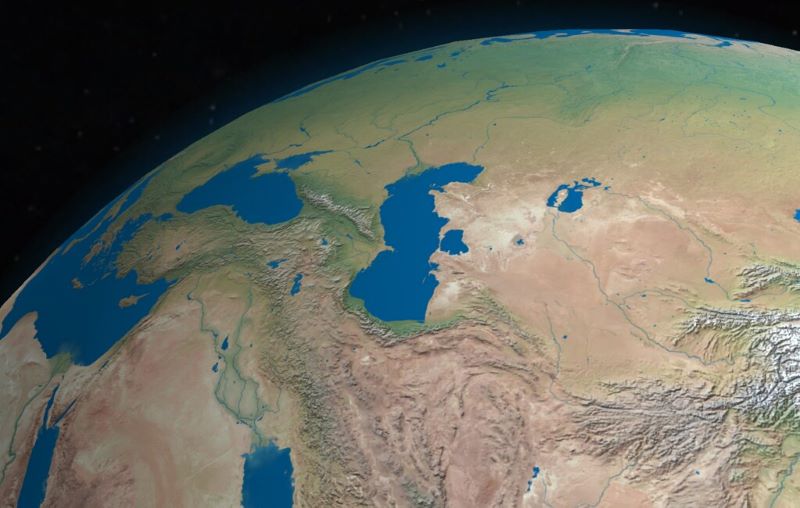

The significance of the SGC for Turkey, the South Caucasus, and Europe is well known. It allows Azerbaijani natural gas to reach Turkey through the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), and later Europe through the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP).

Opening with 6 billion cubic meters per year (bcm/y) of natural gas for Turkey, the pipeline’s volume will increase to 16 bcm/y when the TAP is opened next year. The other 10 bcm/y will land in Italy. Capacity is planned to ramp up to 24 bcm/y by 2023, but since both TANAP and TAP are opening ahead of schedule, it is not impossible that that date is moved up. Then in 2026, the capacity is planned to increase yet again, this time to 31 bcm/y.

It is already understood that these additional volumes cannot come from Azerbaijan. The best candidate to supply them is Turkmenistan. Last August, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan issued a joint public statement (the first between them ever of its kind) declaring the intention to work together to bring gas from Turkmenistan to Europe.

Since then, the Trans-Caspian Pipeline has been confirmed as one of the EU’s Projects of Common Interest, qualifying it for financial support. SOCAR executives at the SGC opening ceremony in Baku clearly stated their belief in this possibility and their readiness to realize it. Advisor to the President of Turkmenistan Yagshygeldi Kakayev endorsed this, and remarks by U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Sandra Oudkirk indicated American support.

The second event mentioned above is the legal move by the Ukrainian company Naftogaz in The Netherlands, that caused to be frozen, in early June, Gazprom’s assets in there, including the project companies for NordStream 2 and TurkStream 2.

Naftogaz has also succeeded in freezing Gazprom’s assets in Switzerland, specifically the NordStream and NordStream 2 project companies. Similar moves are expected to follow quickly in the United Kingdom. These assets were frozen by the courts as a result of Gazprom’s refusal to pay the Stockholm arbitration awards.

Gazprom alleges the presence of “linguistic evidence” that the legal decision was written by some party or parties external to the court. However, an appeal does not cancel Gazprom’s obligation to settle the debt immediately. As the court decisions show, the appeal does not affect the enforcement process either.

The Stockholm award to Naftogaz was for Gazprom’s unilateral increase of gas prices to Ukraine by 80 percent following the Russian occupation of Crimea, and its unilateral imposition of a “take-or-pay” regime, by which Ukraine would have been obliged to pay for the gas whether it actually imported the gas for consumption or not.

As a result, Gazprom has injured the credibility that any assurances that Russia might have given the EU, about maintaining gas flows through Ukraine in the event that NordStream 2 is ever built.

That credibility had already been injured by Russia’s unilateral cut of contracted exports to Ukraine and Europe in winter 2006 and winter 2009: something that the Soviet Union had never done, even at the height of Cold War tensions.

These two events, the SGC’s opening and the Gazprom court decisions in the Netherlands, confirm trends already present for some time in Turkey’s geo-economic energy environment. They confirm Turkey’s central place in the Euro-Caspian meta-region and establish the basis for its further prominence there. Also, together these two events strongly indicate that every effort should be made to implement the extension of the SGC to Central Asia, and Turkmenistan in the first instance.

Photo: “High-Level Russian-Turkish Cooperation Council meeting” (April 3, 2018) via kremlin.ru. Creative Commons.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.