The “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States” executive order is not a Muslim ban, but it is confusing. Though the legislation is clear, there has been much miscommunication between Donald Trump’s administration and the public.

Since January 27, 2017, the day the executive order was implemented, confusion reigned at international airports and embassies around the world. The order suspends the entire refugee admissions system for 120 days, cutting the number of accepted refugees per year from 110,000 to 50,000, while indefinitely suspending the Syrian refugee program.

Most controversial, however, is the banning of foreign nationals from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen for 90 days. Protestors are outraged as some believe that the executive order is a Muslim ban. This stems from Donald Trump’s campaign promise, where he called for a complete shutdown of Muslims from entering the country. Instead of clarifying his intention, Trump stated in one of his tweets that “Everybody is arguing whether or not it is a BAN. Call it what you want, it is about keeping bad people (with bad intentions) out of country.” The tweet has yet to dissuade protestors that the legislation is not a Muslim ban, as Trump has yet to take a stance on the name itself. He is, after all, allowing people to call the order whatever they want. Yet there is nothing referring to the religion of these countries in the executive order. The countries themselves are not even named.

So why were these seven countries chosen in the first place?

In 1986, the Department of Homeland Security issued a Visa Waiver Program which allows foreign nationals from 38 countries to travel within the States for 90 days without a visa. Under the Obama administration in 2014, the Visa Waiver Program was amended to include a terrorism risk factor, allowing the U.S. to revoke travel of person(s) or a country that threaten the security of the United States. In 2015, the bill was further amended, banning those from specifically Iraq and Syria, or other countries where terrorist acts are supported by the government or a “safe haven” is provided for terrorist activities. The list of “other countries” currently includes Iran and Sudan. Finally, after the Paris attacks in November 2015, Libya, Somalia and Yemen were added in February 2016, completing the list of countries making up Trump’s executive ban.

It is questionable as to why Donald Trump has not explicitly stated that the countries chosen for the travel ban – countries whose citizens take no part in American terrorist activities – were not chosen by him, but rather by the Obama administration. Having been extremely critical of the Obama administration during his campaign, Trump’s lack of finger pointing towards the previous government over the decision of the seven countries is curious.

Rather, the seemingly unconventional and inarticulate political addresses to the public have become the main tool of the White House’s policy executions. The battle between the press and White House has been further exacerbated by press secretary Sean Spicer, who has been accused of making false claims, ignoring questions and deliberately choosing certain journalists who are biased towards the administration, not to mention that Spicer has become another White House punchline for SNL.

Throughout the 2016 presidential election campaign, a “heightened awareness” towards Muslims and Islamophobic rhetoric seemed to have surfaced enough for a Georgetown University report to find an increase in negative behaviour towards Muslim Americans. The White House expresses that this order is for the protection of Americans, while many media outlets persist that the administration has an anti-Muslim agenda. Either way, both the White House and the press continue to bump heads over each other’s rhetoric, which has been found to “influence the way Americans treat their fellow citizens.”

This can be seen in the perception of the travel ban by the public. As soon as the travel ban was issued, lawyers around JFK airport in New York City gathered to provide free services to those denied entry into the United States. Attorneys filled the inside of the airport, working with the International Refugee Assistance Project, while protestors gathered outside with signs condemning the new policy as Islamophobic.

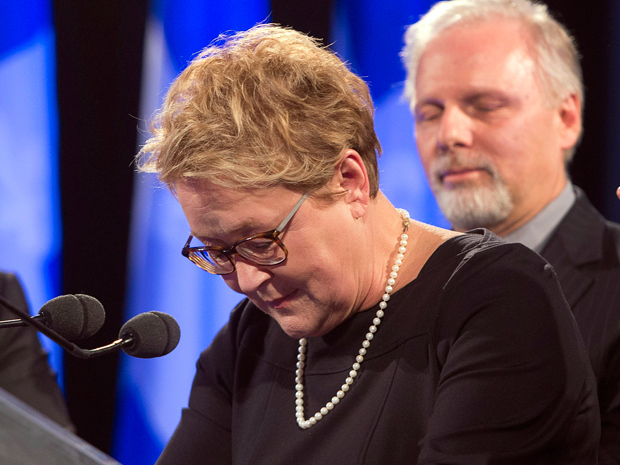

Two days later, on January 29, 2017, Alexandre Bissonnette walked into a Québec mosque, shooting six dead who had come for their evening prayers. Many media outlets focused on Bissonnette’s online support of Trump and the false claim that there had been two shooters, one of whom was Moroccan, and the other whose race was not mentioned.

But even after this information was proved wrong, Fox News remained focused on the “Moroccan shooter,” rather than on Bissonnette. It took a formal letter by Katie Purchase of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) to address this false information. Purchase herself responded by saying, “To paint terrorists with a broad brush that extends to all Muslims is not just ignorant — it is irresponsible.” She emphasized that Canada was open-minded and above justifying the act through identity politics. Purchase felt that it was her duty to ensure the right information got out there. Indeed, after the shooting, Premier Philippe Couillard of Quebec stated that there are consequences to the words we use; “words can be like knives.”

Legally, this executive order is not a Muslim ban. But Trump has used these words, and his White House press secretary is doing a poor job of explaining the legislation to the press, creating a misunderstanding between what the White House is trying to accomplish, and what the public believes their government is trying to accomplish. As the government turns its back on an eloquent and professional political culture, this division may continue.

Photo: “SFO Muslim Ban Protest” (2017), by Quinn Norton via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.