The Scramble to Southeast Asia?

With the exception of China and India, a group of clustered Asian nations have recovered from the financial crisis while gradually picking up pace and elevating the region to be filled with ample opportunities and economic prospects. This region is Southeast Asia (SEA). With close to 605 million people and an estimated gross domestic product of US $2.2 trillion by 2015, there is little surprise that leaders across the Pacific regard Southeast Asia to be the “next big thing” and are all scrambling to court a relationship with nations in the region.

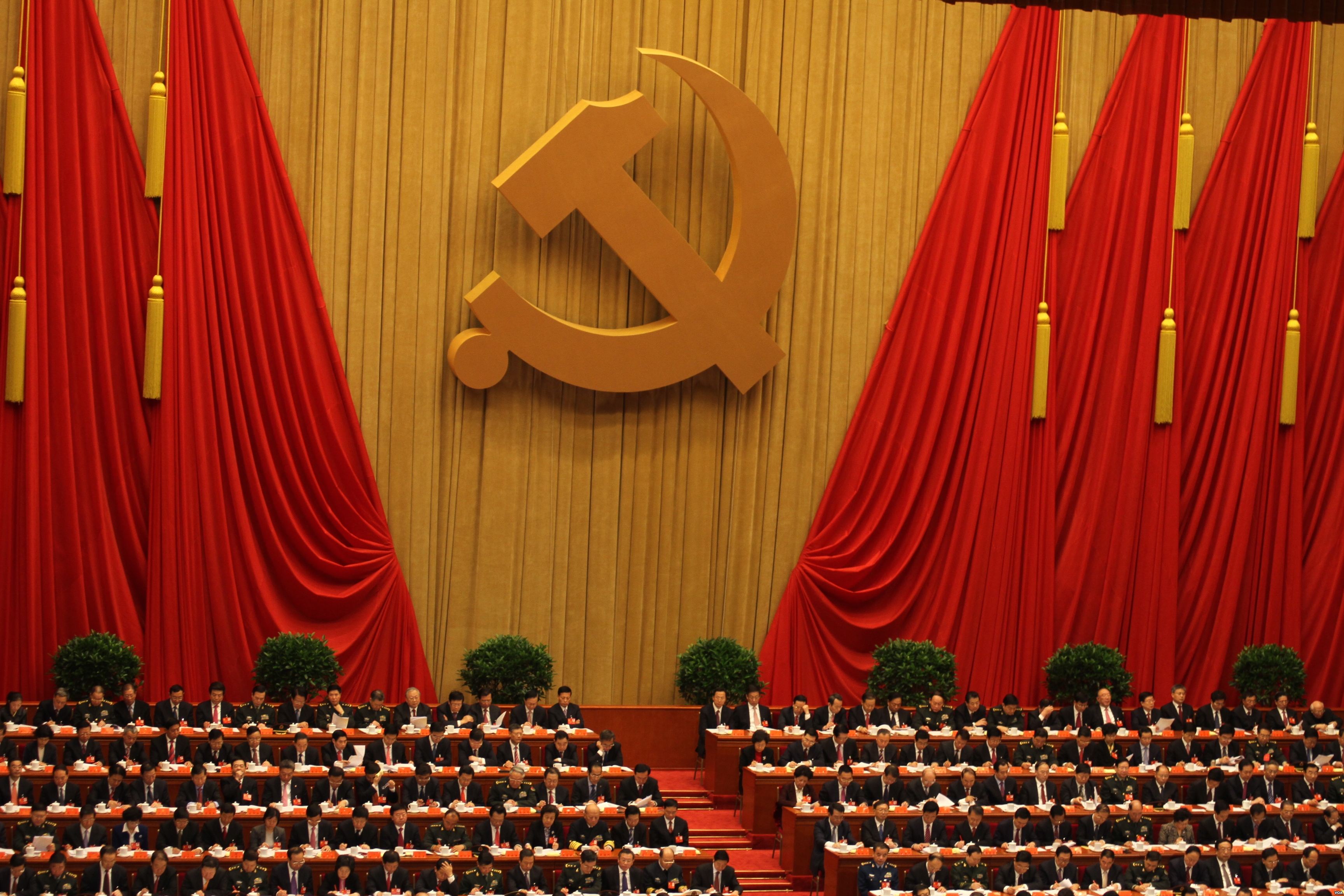

With the continued decline in Europe and an apparent economic slowdown in China and India, the stakes are high and the competition is fierce. At this very moment, while the Americans are losing ground in SEA because of the recent government shutdown. By contrast, China making political moves in the region, dominating the headlines (from the well-received tour of Chinese President Xi Jinping in both Malaysia and Indonesia and his strong appearance as the most dominant leader in APEC, to Premier Li Keqiang’s recent trip to Thailand and Vietnam) and easily winning this round of the showdown with the US.

Canada is no exception in trying to stay connected with SEA. Despite being ridiculed as “almost invisible” in Malaysia and “rather slow” in realizing its promises in regard to diversify trade with Asia, the Harper administration participated in the APEC meetings and took the time to tour the region. In fact, Canada has achieved some of its short-term objectives in SEA, from securing a 36-billion dollar pledge from Malaysia on the construction of a pipeline and the related infrastructures in BC to transport liquefied natural gas to further the negotiation on the ambitious 12-nation free trade agreement known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

John Baird, Canada’s current Foreign Minister, fully acknowledges the growing importance of SEA and reiterates that he will continue to work to further strengthen not only the economic, but also political ties with states in the region. Baird will do this through engagements like the Canada-ASEAN Business Council, a private sector led initiative that engages partners in universities, civil society, business and government across the region. Canada’s ties with Southeast Asia, stated Baird, are indeed “the key to the future prosperity of Canada.”

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://www.vancouversun.com/business/cms/binary/9041627.jpg?size=620x400s ” captiontext=”Canada’s ties with Southeast Asia are the key to prosperity in Canada”]

The addition of Myanmar and Its Significance

Despite all the rhetoric, the truth is that Canada is falling way behind and there is a lot of catching-up to do if Canada wishes to stay relevant in Southeast Asia in the future. For this reason, some international commentators have suggested that Myanmar, a country which recently opened up from a half century of instability and brutal military dictatorship, might be a good place to start. However, “why Myanmar?” is perhaps the question that comes to mind.

To begin with, Myanmar is far from the ideal place for doing business. With the country’s still strict regulation on the economy, the absence of private property, constant human right abuses against the religious minorities and rampant corruption, Myanmar is perhaps one of the worst countries in Southeast Asia, let alone the world, to invest in. However, despite those immense obstacles, the Vancouver Sun is quick to point out that since early 2011 there have been sweeping and swift reforms implemented by the once notorious military junta. Additionally, Myanmar “isn’t just economically opening up, as in China and Vietnam. They (the government) is trying to do a political reform and a social reform at the same time.” Adding to the reforms is the economic potential Myanmar is poised to achieve. With a population of around 60 million, the country is expected to grow fourfold by 2030, which in turn will enable 19 million people (from 2.5 million) the ability to purchase consumer goods. Thus, in spite of the obvious problems it faces, Myanmar is a country to watch.

[captionpix align=”right” theme=”elegant” width=”300″ imgsrc=”http://previous.presstv.ir/photo/20130307/yasaman.hashemi20130307105130497.jpg” captiontext=”China has actively been seeking an alternative to the Strait of Malacca”]

“The Devil’s Neck” and Myanmar’s Geographic Location

Situated in the crossroads of some of the world’s most populous and fastest growing countries, Myanmar’s geographic location and vast population are two key factors influencing its economic potential. The country is a bridge that links South and East Asia. More importantly, Myanmar occupies the eastern end of Kra Isthmus, the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula, and cuts off the waterways that connect Southeast Asia to the Indian Subcontinent (more specifically, it divides the Bay of Bengal from the Gulf of Siam, and India’s ports from East Asia’s). Historically, this narrow stretch of Isthmus is known as the “the Devil’s Neck” as Europeans, Indians and people in Southeast Asia alike all dreamed of breaking through the landmass in the hope that ships could save between 28 to 40 hours by avoiding the long stretch of the Strait of Malacca.

Today, the dream of building a canal that would channel through the isthmus has largely faded, but because of Myanmar’s recent opening and its strategic importance and geographic location, the country’s powerful neighbours (some of world’s soon-to-be superpowers and middlepowers to be sure) all want a piece of the pie. China has long dreamed of having an energy supply (primarily from the Middle East) that does not pass through the Strait of Malacca and the Taiwan Strait, both waterways well known for a strong American presence. Myanmar thus becomes a natural choice for China to transport the necessary energy. In fact, China has already secured the access to the coast of Mynamar and Beijing is poised to build an 800km pipeline that will run across all of Myanmar’s northeastern province before entering China’s Yunnan provinces. In addition, Thailand, India and other Southeast Asia states all have plans of their own to utilize Myanmar’s recent opening to broaden their trade routes. In short, with the addition of Mynamar as a place for future economic development, Southeast Asia is on pace to be on par with China and South Asia as the next key player in the global economy .

(To Be Continued: What Can Canada do in Myanmar and Southeast Asia?)