In 2002, the US Naval Research Laboratory released its first version of “Tor”, a software capable of granting users complete online anonymity. Originally designed for the US Navy, Tor sought to protect sensitive government communications from the public eye.

The idea was fairly simple: instead of travelling directly from user to user, dispatched data would hop around different computers, encrypting its tracks differently each step of the way. Each of these computers, volunteered by owners around the world, would ignore the kind of encryption used at previous relay points, preventing the whole route from ever being identifiable. In other words, by the time any data would reach the recipient user, its original starting point would prove impossible to trace.

Despite its intended military use, Tor quickly became a popular tool amongst private individuals. Its ability to bypass online censorship and detection provided safe haven for state-monitored citizens, oppressed whistleblowers or endangered journalists.

In China, for instance, an increasing number of citizens use Tor to circumvent “The Great Firewall”, accessing government banned websites without fear of reprisal. In Egypt, in 2011, Tor reported a surge in local connections following the country’s severance of internet connections, a measure seeking to quell mass protests. A similar surge was observed in Turkey last month as the government cracked down on social media networks. Tor is so powerful a tool that international training institutes teach human rights activists to use the software in order to report violations or organise campaigns. Tor has also soared in popularity amongst average citizens seeking to further protect their internet privacy following the NSA surveillance revelations.

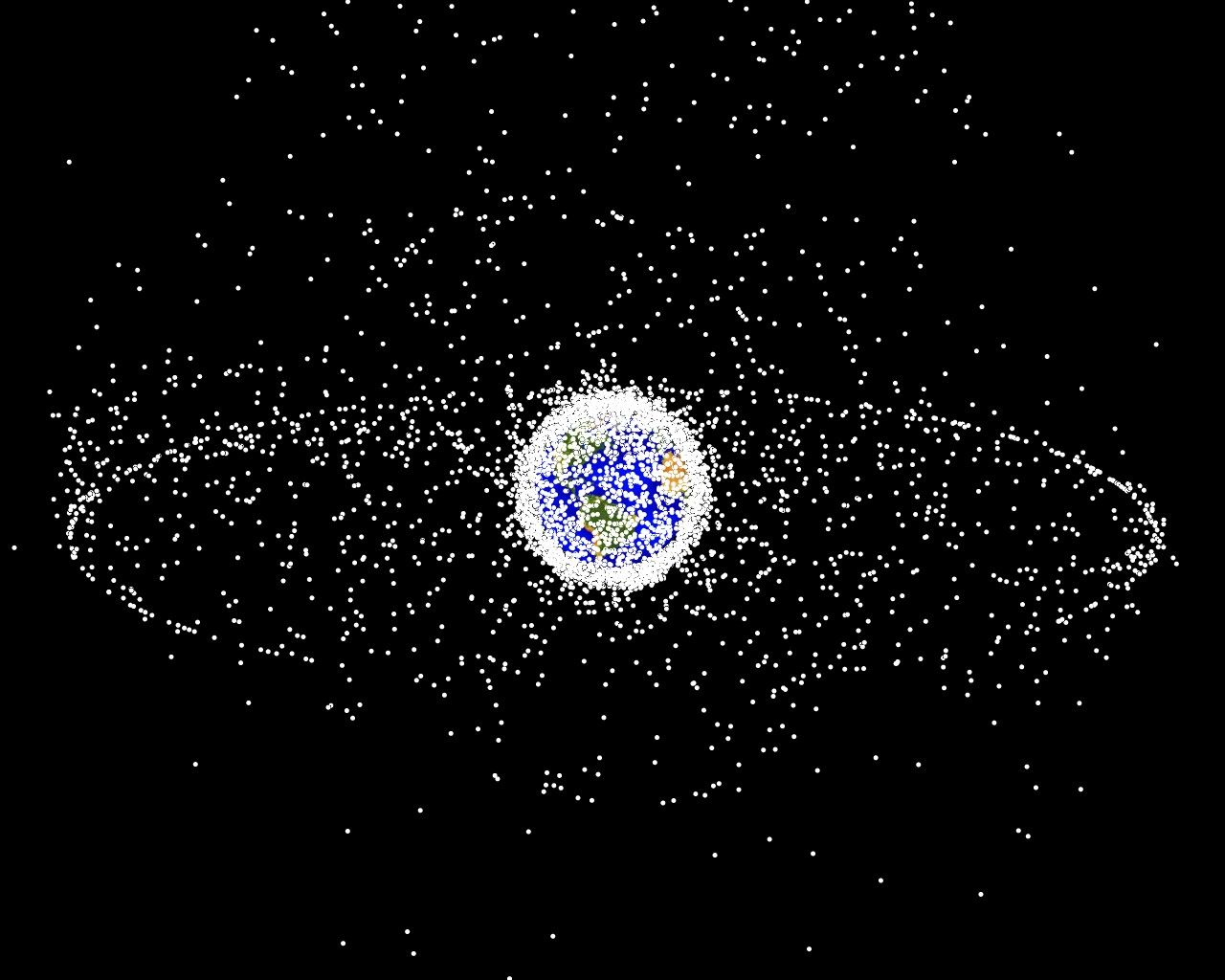

Unfortunately, online anonymity is a double edged sword. Whereas some saw Tor as a valuable communication tool or human rights safeguard, others perceived it as the perfect criminal aid. The anonymity provided by Tor allows users to access the notorious “Deep Web” or “Invisible Web”. The latter consists of websites or shared databases that aren’t indexed by common search engines, such as Google or Yahoo. These sites, an estimated 96% of the internet, are therefore very difficult to find, requiring the user to have been given the exact, up-to-date address (many of them move around periodically so as to avoid detection).

This concealed arena provides an ideal blueprint for cyber-criminals around the world. For years now, the Deep Web has lent itself to online drug trafficking, weapons trade, the live streaming of sexual abuse and worse. Its most infamous online market, “The Silk Road”, only draws a feeble line at the sale of child pornography, stolen credit cards and weapons of mass destruction. However, FBI investigations revealed that the site did offer tutorials for hacking ATM machines or contacts for hit men and counterfeiters. All of the aforementioned services were paid for using Bitcoin, a digital currency much harder to trace than a regular credit card — each year, $15 million worth of bitcoin transactions are estimated to take place on the Silk Road.

The seemingly benevolent increase in the worldwide availability of high-speed internet can actually lead to new and growing forms of cyber-exploitation we have yet to gather the tools to fight.

For lawmakers and law enforcement, the Deep Web and its illegal markets present a growing worry bearing international implications. Efforts to combat and regulate this twisted haven of anonymity are often poorly funded and too thinly spread, yielding poor, short-lived results. Following the October 2013 arrest of its founder, 29-year-old Ross Ulbricht, the Silk Road was temporarily shut down. However, other competitors quickly lined up to become the next go-to market, leading to a 75% growth in the Deep Web drug economy over a 6-month span. Even the original Silk Road itself returned, run by a new manager, and is allegedly doing better than ever.

This all too rapid recovery of one of the world’s biggest black markets is but a symptom of a new, fast-paced era of cyber-crime that law enforcement agencies have yet to adapt to. Although many see the increasing worldwide availability of high-speed internet as progress, it can also, when hand in hand with extreme poverty, lead to new forms of cyber-exploitation we have yet to gather the tools to fight. In January 2014, 17 British men were arrested and charged with the organised streaming of real-time child sexual abuse from the Philippines – an emerging criminal trend, according to the British National Crime Agency.

Surprisingly, this manifest shift from traditional crime to cyber-crime has not lead to a parallel evolution in law enforcement. National police forces have repeatedly asserted that the combat of online crime is not adequately funded and lacks the necessary, skilled personnel. There is a further matter of jurisdiction: to what extent can national agencies regulate an entity as transnational and border-free as the internet? Will not a repressive regime in one particular country merely lead to the relocation and continued existence of cyber-crime rings in another? How can legislation be harmonised in order to prevent criminal migration waves?

Increasingly obvious is the conclusion that any effort to combat cyber-crime must take place on an international platform. Whereas some transnational entities, such as the EU, already have a specific cyber-crime task force, others have yet to play catch up. Many of the existing international cyber-crime conventions are outdated; new proposals have been rebuked. Existing platforms such as Interpol, an inter-governmental organisation facilitating police cooperation, are having difficulty working with key private sector actors, specifically mass data-collecting firms. Finally, the recent wave of NSA revelations has sprouted skepticism and suspicion in an audience whose trust needed to be gained in order to work towards better internet regulation.

These obstacles have to be surmounted before we pay the price with our right to certain types of technology. Bitcoins are a fantastic tool for commerce and are in and of themselves completely harmless. The same can be said for encryption mechanisms or online anonymity in general. However, the less cooperation and the more frustration there is in the combat against cyber-crime, the keener law enforcement agencies will be to ban once and for all these precious digital tools that could have painted us a very different future.