According to a report made public on Thursday, January 28, 2016, the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) has stopped sharing metadata with its partners in the Five Eyes global intelligence group after finding that personal information from Canadian citizens may have accidentally been given to foreign governments.

In a press release from the Government of Canada regarding the annual CSE external review, it was revealed that the “CSE discovered on its own that certain types of metadata containing Canadian identity information were not being minimized properly before being shared with CSE’s partners in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand” and that, in response, the CSE has voluntarily suspended its information-sharing practices for further assessment.

The Honourable Jean-Pierre Plouffe, the CSE Commissioner overlooking the review, confirmed that the mistaken distribution was due to a software flaw rather than an intentional practice. Defense Minister Harjit Sajjan has publicly reassured that “the privacy impact was low.” Regardless, as Canadians with data likely implicated in this recent case, it is worth looking into what information was at stake and who had access to it.

Metadata is the information collected about the modes of communication used by an individual; when you use your cellphone or computer, details like your phone number and IP address and details about when and where you used those tools are swept up en masse. While metadata does not include the content of the messages being communicated electronically, it is possible to learn a lot about one individual by analyzing the informational dots collected over a period of time (one of the big revelations from the Snowden leaks in 2013).

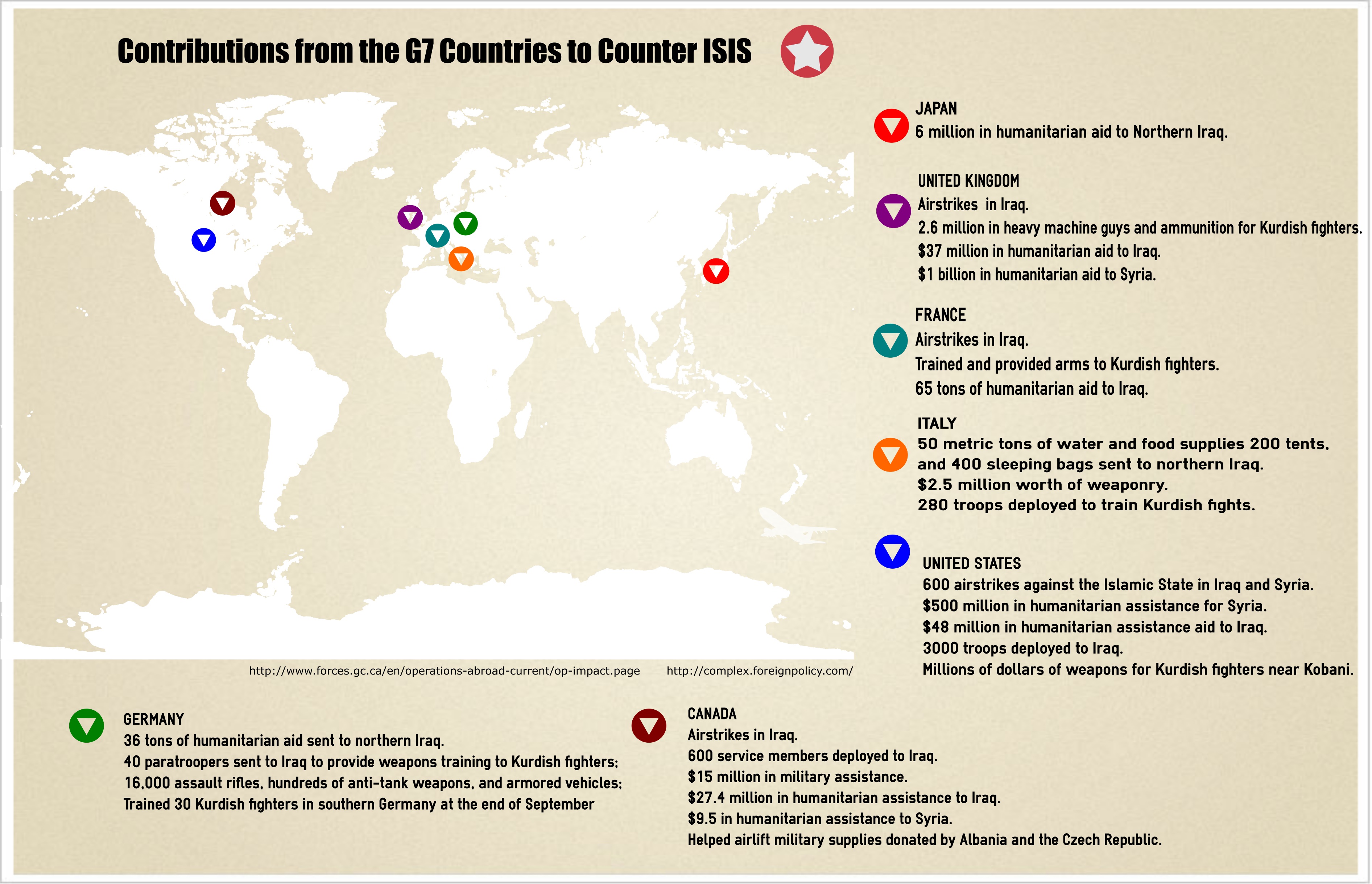

Canadian metadata collection is just one piece of the global information pool. Governments all over the world have been collecting this information about their citizens and, in an effort to keep their citizens safe, sharing that information with other governments. The CSE in particular has been sharing information with the Five Eyes, an intelligence partnership between agencies in Canada, the US, Britain, Australia, and New Zealand created after WWII.

Metadata is invaluable for security purposes. For any one group, ‘connecting’ the dots could allow intelligence organizations to identify national security threats and take further investigatory steps towards preventing serious attacks. By engaging in information-sharing, intelligence bodies are enlarge the pool of dots, expanding coverage to detect globally coordinated attacks.

Despite the CSE exposing its own technical defect and reacting quickly to protect Canadians’ privacy, this case does reveal some of the risks associated with state-to-state information sharing. If some of your personal details are caught within the metadata, it means foreign governments may have direct access to your private information whether or not it intentionally wanted it. There are also domestic implications for improper metadata sharing. Plouffe suggested that the CSE’s distribution of Canadians’ personal information to members of the Five Eyes may have violated Canada’s National Defence Act and Privacy Act.

Canadian privacy advocates are not very happy with this privacy breach. Laura Tribe, a digital rights specialist at OpenMedia, has argued “no Canadian should need to fear that their private information is being handed to foreign agencies by their own government.” At the same time, though, researcher Bill Robinson has pointed out that “this is the first clear instance of a commissioner declaring that CSE did not comply with the law.”

Defence Minister Sajjan declared that the “CSE will not resume sharing this information with our partners until I am fully satisfied the effective systems and measures are in place.” Though suspended for now, the reality is that the information sharing is happening and will most likely continue as it is. There is a large national security incentive for governments to share metadata, especially as governments are responsible for the security of their citizens. The public does expect governments to uphold that responsibility. Many times after past terrorist attacks, the public has been quick to criticize national security agencies for failing to connect the dots and prevent the attack despite having collected the information necessary to do so.

That being said, as citizens of those governments this is still our information being shepherded around. This breach in the CSE should serve to remind us what could happen to our information if we do not keep a constant eye over these digital practices. While we are still working towards a balance between national security and privacy priorities, it is important to remember that when it comes to private information about yourself, you still have the right to ask for your personal security.