The upcoming Munk Debate on Foreign Policy, Canada’s first-ever federal election debate devoted to foreign policy issues, is scheduled to take place on Monday, September 28. This is a welcome addition to the election debate schedule, according to Munk Debates Chair, Rudyard Griffiths, who issued a press release arguing “too often, foreign policy issues have been afterthoughts in past federal elections.” To observers of Canadian elections, this rings true. Given that Canada’s foreign policy efforts are rarely essential to national security, international relations have not taken the prominent position on the national political agenda that they have in, for example, the United States or in Arab countries. The last election in which a foreign policy issue was decisive was in 1998, when Brian Mulroney sought a mandate to conclude with the US Free Trade agreement.

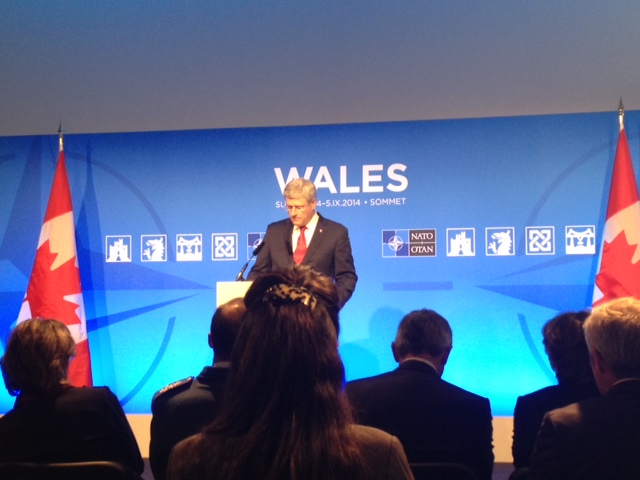

There are those who argue, however, that 2015 will be a landmark election for foreign policy issues. Canada has seen an exceptional shift in its foreign policy since Prime Minister Harper stepped into his role. Since 2006, the Conservative government appears to have distanced itself from multilateral institutions such as the UN, focused on trade negotiations and bilateral relations, and demonstrated increased willingness to deploy military forces overseas.

The latter point is the most contentious, but perhaps the most agreed upon: in an article for Canadian military magazine Esprit de Corps, former Canadian Armed Forces soldier Robert Smol writes, “If there is one perception of Canada’s military that both the left and right can agree on, it would be that our military is bigger, better equipped and more operationally active under Harper.” During the Conservatives’ first six years in office, the military budget increased from $15 billion to $23 billion. In addition to increased spending, they have added thousands more troops and bought new tanks, helicopters and transport planes. “The decision to acquire four C-17s for strategic airlift indicates the government’s intention to utilize the CF [Canadian Forces] more extensively off continent,” reads a May 2010 briefing note signed by then Chief of Defence Staff Walter Natynczyk.

Pundits fall on either side of the fence when commenting on this shift: some call it a “fairly incoherent foreign policy”; others say that the country has developed “a reputation for being disengaged on many issues and obstreperous on others.”

While others defend the changes, arguing that they reflect a “different kind” of internationalism.

With these shifts, many have argued that foreign policy will matter like never before in the 2015 election. In an article for the Globe and Mail, John Ibbitson predicts: “both trade and geo-politics are going to be on the agenda. Dealing with Vladimir Putin will be as important as dealing with the premiers. Stephen Harper, Thomas Mulcair and Justin Trudeau will be judged on how they would represent our country in the world.”

In anticipation of this possibility, and of the Munk Foreign Policy debate, this two-part article will give a rundown of the three main issues in Canadian foreign policy.

Canada-US Relations

Canada’s relations with her formidable neighbour to the south will be a central focus of the foreign policy debate. The Liberal and New Democratic Parties will accuse Prime Minister of Harper of mishandling Canada-US relations.

Experts differ on whether Canada-US relations have soured, and if so, on the extent to which they have. Michael Kergin, Canadian Ambassador to the U.S. from 2000-2005, claims “our two countries seem to be in an almost unprecedented situation of non communication at the level of their leaders,” citing the recent postponement of a scheduled North American Summit meeting to be held in Canada as a dramatic example. Derek Burney, a former ambassador to the U.S., agrees that Canada-US relations have cooled. He argues that “the fault lies with the White House, its indifference towards the interests of its key allies and neighbours, and its toxic relationship with Congress, which has caught Canada in the down draft on many issues.”

On the other hand, Colin Robertson, former Canadian diplomat to the United States, calls for Canada to work to build and maintain the relationship. “First, you need to understand the United States,” he calls, “it’s more than a country – it’s a civilization. Second, advancing our interests means engagement at every level.” He believes that in the future, the initiative must come from Canada.

On Monday, Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau will undoubtedly argue that Harper has damaged Canada’s ties to the U.S. He claims that, if elected, he will put more focus on Mexico. He has also pledged to create a committee of cabinet ministers dedicated to overseeing Canada’s relationship with the U.S.

The NDP have taken a significantly more ambivalent stance on Canada-U.S. relations. During Tom Mulcair’s 2013 trip to the US, his spokesman stated that “the decision on Keystone lies with the Obama administration, and he is not here in Washington to tell the US government what to do.”

Foreign Affairs Minister Rob Nicholson has said that the two nations are working together to “expand trade, grow our economies, and take decisive action against threats to our national security, including the mission against ISIS.”

In July, CBC reported that things were looking up: U.S. Ambassador to Canada Bruce Heyman said in an interview “things are going significantly better than the news might have reported.” On Monday, Stephen Harper will likely draw on this upswing, to defend his stance on Canada-U.S. relations.

In our next section, we’ll discuss Canada’s approach to multilateral institutions and its engagement with the Middle East. Stay tuned!