On August 26, 2022, NATO’s Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg warned Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau about Russia and China’s investments and intentions to build military, commercial, and industrial capacities in the Arctic. This is not new information. Russia and China made their Arctic strategies publicly available in 2009 and 2018, respectively. News articles frequently detail their interests and successes in the region. Despite this, Canada has not yet developed a comprehensive Arctic strategy. Following this call to arms from the NATO Secretary General, the US released a National Strategy for the Arctic in October 2022, leaving Canada as the only Arctic Nation without such a policy. Canada must follow suit and honour its 2016 promise to create a comprehensive Arctic policy. Now more than ever, Canada requires a strategic plan to protect its sovereignty against the threat posed by having two nations with track records of ignoring international law and human rights heavily invested in the region.

Until now, the concept of Arctic exceptionalism has been popular in the security field. The term was first introduced in 1987 by the then General Secretary of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev during his “Zone of Peace” speech. It refers to the idea that the Arctic is an area of the globe that sees little to no conflict and is peaceful, even in the face of great power rivals Russia and the US sharing a border there. The concept, although partially correct, conceals the ongoing tension that has been brewing between Russia and NATO allies for decades. Gorbachev’s speech, rather than a description of reality, was an invitation for cooperation and dialogue on and in the Arctic that foreshadowed the creation of the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum where the eight Arctic states meet and discuss how to peacefully coexist there, by nearly a decade.

Geopolitical tension in the Arctic is now based on the tripartite great powers competition erupting between Russia, China, and the NATO alliance in their quests to be the dominant actor in the region. Since the end of the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the US have had competing scientific research programs and investments in the region, with both nations vying for informational and military supremacy. Throughout the Cold War, the Arctic Ocean became increasingly militarized with submarines prowling below the surface of the water while bombers flew overhead. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia continued to contend for authority over the region, planting a flag pole on the ocean floor of a contested continental shelf near the North Pole in 2007 in an attempt to claim the natural resources potentially buried underneath. Since 2014, Russia has continued pursuing its interests in the Arctic, modernizing and investing in a command post for its Northern Fleet, working to protect and control its maritime shipping Northern Sea Route, and creating nuclear-powered icebreaker ships to keep the Route open year-round.

In the last seven years, China’s ambitions to expand its Belt and Road initiative into the Arctic as a Polar Silk Road have also become clear. Since 2018, China has claimed to be a “Near-Arctic State,” stating that melting ice in the Arctic has global impacts and is therefore in the country’s interest. China is heavily invested in the financing of Russian oil and gas projects in the region and is interested in prospective financial gains associated with faster maritime shipping through the region. The state is also in the process of procuring a fourth Arctic icebreaker to expand its ability to transit polar regions year-round.

Along with demonstrating its Arctic ambitions, China has demonstrated that the country does not respect the rules-based international order. In recent years China has not only challenged the sovereignty of Taiwan, it has also repeatedly restricted its citizen’s rights, including the rights of its minority populations. Following the lead of the US, Canada’s parliament declared China’s treatment of its Uyghur population to be genocide in February 2021. Although internationally recognized, these human rights violations continue to go unpunished as China firmly denies all allegations of wrongdoing.

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine last February demonstrated that it too will not respect the sovereignty of other nations or human rights. By annexing Crimea in 2014 and invading Ukraine in 2022, Russia has shown that it cannot be trusted to respect the rules-based international order either.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and aggressive rhetoric against NATO have severely strained relationships between Russia and the rest of the Arctic Council, who are all member states. Consequently, the Arctic Council suspended communications with Russia on March 3, 2022, putting an abrupt end to any cooperation between Russia and the Council. In 2024, the Arctic Council announced that its working groups have resumed project-level meetings. However, this resumption has not restored relations between Arctic states. Without open dialogue and strong bi- and multilateral relationships between all Arctic states, the façade of Arctic exceptionalism has rapidly crumbled, leaving experts convinced that there will be increased military activity in the region in the coming years.

Although NATO’s last Strategic Concept paper was adopted in June 2022 without any mention of the Arctic, Stoltenberg is now publicly addressing the increased tension there. Fortunately, Canada’s recent Arctic defence initiatives are reflective of NATO priorities. Canada has procured six military Arctic Offshore Patrol Ships and announced that it will invest CAD $38.6 billion to update the North American Aerospace Defense Command’s continental defence capabilities. However, without a comprehensive Arctic strategy, Canada remains unprepared to address intensifying threats facing the Arctic.

NATO allies, including Canada, need to acknowledge Stoltenberg’s statements and work together to develop defensive capabilities and strategies that protect their Arctic sovereignty and citizens. If the past two years has shown us anything, it is that you can never be too careful around belligerent actors. Canada can no longer afford to be a laggard. Russia and China have Arctic interests and capabilities, have demonstrated that they are willing to breach international laws, and do not respect the sovereignty of other nations. If Canada wants to ensure that their interests and the rules-based international order are protected in the region, the government must keep its 2016 promise by expediting the creation of a truly comprehensive Arctic policy framework.

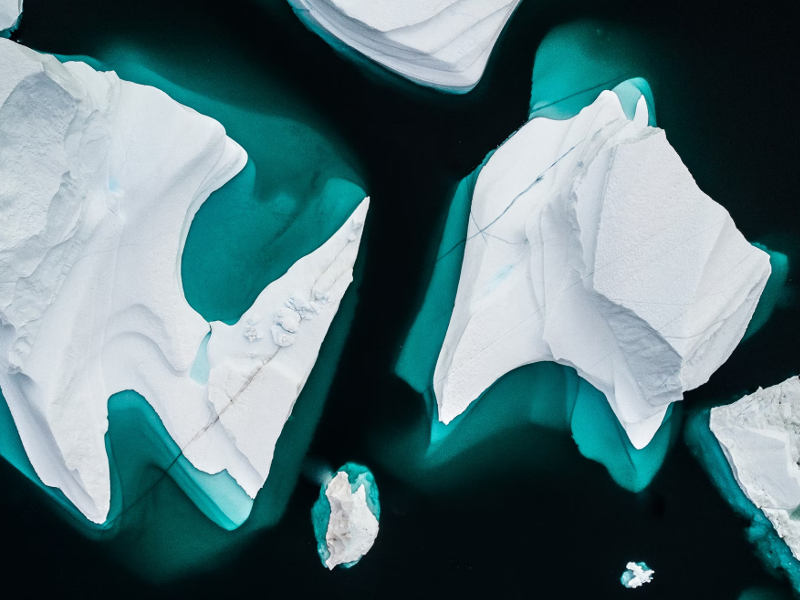

Photo: Aerial image of an iceberg at Scoresby Sound, Greenland, taken with a drone via Annie Spratt on Unsplash, 2018

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.