Last week, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that Canada will contribute to the multilateral campaign to “degrade and destroy” the Islamic State – but not in an overtly military role for the time being. While Canada’s stated commitment to the effort leaves much room for interpretation and future expansion, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) appears to have little part to play in this conflict, in contrast with recent Canadian military operations. While this may change as the situation evolves, recent cuts to the RCAF may partly account for this reluctance to use air power.

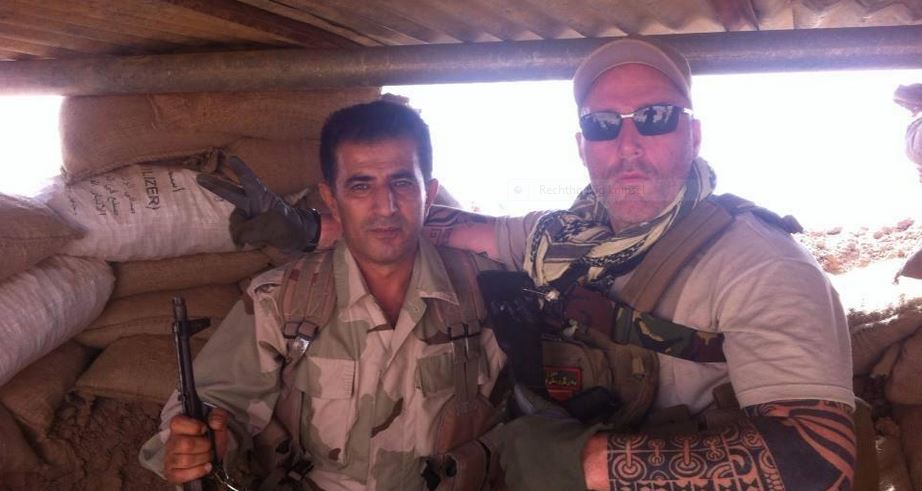

From what the Canadian government has said thus far, there appear to be three dimensions to the upcoming Canadian involvement in Iraq. One is the contribution of two military transport aircraft to deliver humanitarian aid. Another is that Canada has committed to help arm Kurdish forces in northern Iraq. The third is the deployment of “a few dozen” military advisors to provide “strategic and tactical advice” to the Kurds, with this deployment to be re-evaluated every 30 days. The government has made it clear that there will be no combat role for Canada at present, and there has been no discussion of addressing the Islamic State (IS) in Syria. While this involvement is certainly limited at the moment, some speculate that the government is poised to ramp up the level of engagement, as Harper has noted that “further steps” may be “evaluated” in the future.

In recent foreign interventions, Canada has made extensive use of air strikes alongside its allies. Canada contributed substantial air power to the 2011 NATO intervention in Libya, which also involved a rebel force doing the heavy lifting on the ground, much as the Kurdish peshmerga are doing in Iraq. Canada also participated in the successful NATO bombing campaign in Kosovo in 1999, and has now sent CF-18 fighter jets to Lithuania to “patrol the air” in a clear show of NATO strength directed towards Russia in wake of its aggression in Ukraine. In the war-weary post-Afghanistan era, air strikes are a relatively palatable option for the Canadian public once inaction in a conflict is deemed no longer acceptable.

But, in addition to a public aversion to war and the caution being urged by opposition parties, issues within the RCAF itself may prove to be the harbinger of a less active air force for Canada in Iraq and beyond. The reality that Canada’s “aging” fleet of CF-18 jets will soon need to be replaced makesthe F-35 procurement debacle, and the associated challenges of purchasing an expensive new generation of Canadian jets a serious problem. However, problems may run deeper than just the protracted upgrading of out-of-date planes.

A report by David Pugliese of the Ottawa Citizen on September 8 noted that Canadian military spending has dropped to just one percent of GDP—well below the 2% benchmark that NATO asks of its members—and that the RCAF’s budget has been cut by 13% for this year. While such cuts will have an impact on virtually all aspects of the RCAF’s operation, missions conducted abroad in conjunction with NATO may be some of the first casualties. While the Citizen notes that “the RCAF remains capable of conducting overseas operations,” the Air Force’s 2014-2015 business plan warns that “certain NATO commitments may be at risk,” and adds that “a review of the [RCAF’s] ability to meet the current level of NATO commitment” may be warranted. The RCAF also stated in the business plan that it would put its limited resources towards “force generation activities” that are “largely limited to main operating bases,” thus likely impacting the Air Force’s capacity to operate with allies overseas.

Canada has consistently employed the RCAF as a vital tool when contributing to NATO-led missions in recent years. The Air Force’s budgetary issues, however, may cast doubt on whether that strategy will survive much longer. Within the context of a Canadian public that is weary of military involvement in the Middle East, increasing RCAF funding may not prove tolerable for voters. Canada may indeed eventually join its southern neighbour in delivering air strikes to stem the tide of IS expansion. If, however, Canada’s engagement in Iraq remains limited to the role described by Canada’s leaders, this may foreshadow what future Canadian involvement in NATO missions—with a diminished RCAF—may look like.