Tensions are on the rise in Nagorno-Karabakh, an unrecognized autonomous region of Azerbaijan inhabited mostly by Armenians. Armenia and Azerbaijan fought a bloody six-year war over the territory after the collapse of the USSR, with tens of thousands of civilians displaced. Several weeks ago, the deputy speaker of Israel’s parliament called in an op-ed for a mass ‘transfer’ of Palestinian civilians out of Gaza, with the territory to be annexed by Israel. In South Sudan, Iraq, and Syria, millions are being forced to flee their homes and livelihoods by armed militias due to their ethnic or religious background. This phenomenon has a name: ethnic cleansing.

Ethnic cleansing is defined as “the attempt to create ethnically homogeneous geographic areas through the deportation or forcible displacement of persons belonging to particular ethnic groups.” This is accomplished through the threat or use of persecution and violence against civilian populations of the targeted ethnic group. Religious or ‘sectarian’ groups can be targeted as well for ethnic cleansing, despite being a non-ethnic community. While ethnic cleansing often occurs alongside genocide, it is differentiated by its intention. Genocide seeks to annihilate part of or the entire targeted group, while ethnic cleansing seeks to forcibly relocate them. While in reality the two crimes often blur together or coincide, there are important differences in their outcome and solution.

Although it has been practiced for millennia, including by both the United States and Canada, ethnic cleansing as a modern policy has its roots in the rapid rise of nationalism. By the early 20th century, the multiethnic dynastic empires that ruled much of the globe, such as Russia and Austria-Hungary, were beginning to crumble. Communities within these empires demanded freedom in the form of their own nation-states. However, populations were often highly intermixed, with enclaves of one ethnicity in majority areas of another, parallel class and ethnic divisions, or historically important regions being inhabited by another people. The combination of overlapping nationalist demands and weakening central authority was explosive.

The devastation of the Balkan Wars and the First World War precipitated an era of unprecedented ethnic conflict. Populations were ‘disentangled’ through violence, as new nation-states sought to ‘cleanse’ their borders of minority groups. For example, many Greeks were expelled from Turkey in the wake of a Greek military retreat in Anatolia, while Muslims fled Greece for the new Turkish republic that emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. An eventual accord settled this de facto population exchange in 1923. Ethnic cleansing also occurred en masse during and after the end of the Second World War, with the tragedies of the Holocaust, the displacement of millions of Germans from Eastern Europe in response to Nazi atrocities, and the Soviet ‘relocation’ of restive ethnic groups to Central Asia.

A similar wave of nationalist conflict took place after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Ethnic warfare took place primarily in the Caucasus and Yugoslavia, where the longstanding socialist regime, riven by economic problems and ethnic tensions, imploded causing a nearly decade-long period of ethnic strife that killed hundreds of thousands of people and displaced millions. This war, which featured concentration camps, the use of rape as a weapon and the systematic execution of men and boys, brought the term ‘ethnic cleansing’ into public awareness. Recently, this common trend has continued from Rwanda to Iraq: the combination of failing central states and competition between empowered, mobilized ethnic groups leads to conflict, which often results in ethnic cleansing.

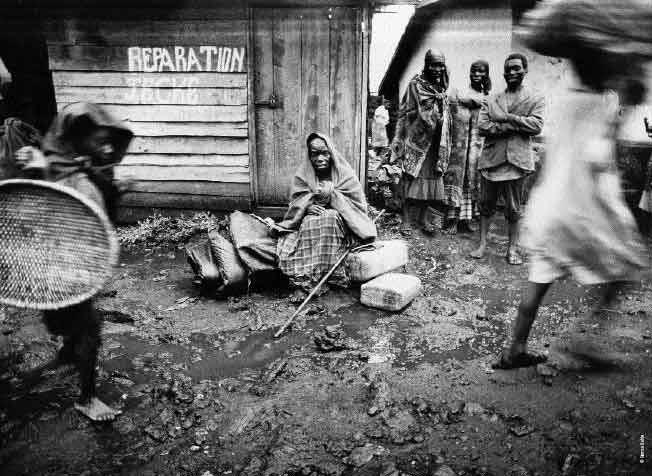

Ethnic cleansing is primarily used to eliminate competitors for political power within a given territory. Tactics range from relatively soft forms of persecution, meant to encourage ‘voluntary’ migration, to terrorism, pogroms, mass arrests and internment, ‘concentration’ of populations and, frequently, indiscriminate violence. Ethnic cleansing is often used to create ‘facts on the ground’, as it is difficult to reverse the expulsion of a population and their replacement by members of the ‘correct’ ethnic group, who will then resist being displaced. This is useful for nationalist regimes with territorial ambitions; ethnic borders will likely remain in place regardless of the result of the conflict. Ethnic cleansing is also used to hurt an enemy’s combat effectiveness. By displacing civilians, the perpetrator forces their enemy to take care of refugees while also confiscating their wealth. Moreover, ethnic cleansing is used to combat insurgencies by depriving guerrilla forces of ‘refuge’ among civilian populations through indiscriminate violence.

Ethnic cleansing is an important issue for international actors for a number of reasons. First, ethnic cleansing is an international crime. Institutions such as the International Criminal Court and its ad hoc predecessors have proven to be an appropriate venue to deal with these types of transgressions of international law. However, as perpetrators of ethnic cleansing often have some level of popular support and state protection, it is difficult for them to be properly punished. Second, ethnic cleansing empowers radicals on all sides of a conflict. In Iraq today, the expulsion and massacres of Shi’a civilians from territory controlled by the self-proclaimed Islamic State has sparked counter-massacres of Sunnis by government-backed forces. Such conflicts can permanently break countries by creating failed states that become breeding grounds for violence, extremism and organized crime. Finally, the refugee movements and devastation created by ethnic cleansing strategies can destabilize neighbouring countries, especially if they also contain a high degree of ethnic diversity. This is clear in the case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where spillover from the Rwandan genocide led to the outbreak of a brutal war in the country’s eastern provinces. Too often, the problems created by instability eventually become the problems of the international community.

The world has yet to develop a response to the symptoms of conflicts in multiethnic societies. However, the catastrophes created by these conflicts are real, destroying millions of lives and causing massive disruption to the international system. For this reason, the crime of ethnic cleansing remains an important issue for the international community.