The NATO Association of Canada’s editors share their thoughts this week on what NATO’s expansion (or lack thereof) could look like based on today’s international relations.

Olivia Cretella

Strategic partnership is a concept that allows for two or more countries to improve or enhance relations in order to maximize their abilities to achieve positive international or domestic objectives. In other words, countries get together to use each other to achieve their own personal goals in an informal way; these can be short-term. These partnerships do not involve treaties or any sense of formality. Alliances, like NATO, involve formal acknowledgement of relations and oftentimes security obligations that are committed to by those countries involved. These tend to be more long-term, as one can see that NATO has been around for almost 73 years now. This is all to say that NATO does not need to increase membership in order to ensure security and contribute to the global balance of power. The continuation of formal NATO expansion will likely only make the international sphere a more complicated community. Countries that want to work with NATO, and have interests that they think NATO can serve, should be able to do so through strategic partnerships.

The problem is, it seems, that NATO has lost its path in what exactly it wants to achieve, and what exactly its definitive goals are. This can be seen in the fact that NATO leaders are stepping up to say: “How do we consolidate all the security interests of each country in NATO, and pursue them?” There has been a call to revitalize NATO’s grand strategy. The situation in Ukraine should be a testament to this. With every NATO country having one foot in and one foot out for Ukrainian support, Germany and France’s strong objections to Ukraine joining NATO, and an overall disparity in goals, NATO is in no position to continue formal expansion.

NATO’s focus on strategic partnerships, especially as seen in the NATO 2030 global approach, can serve the organization much better in continuing to promote security and stability in the globe. This approach will also help to enhance the international rules based order without backing adversaries into a corner with the nature of formal alliances. Though it is not likely that Putin sees NATO as an actual threat to Russia’s security, he will frame it in such a sense on the basis of adding Ukraine to the formal alliance. It is wise all around to avoid giving Putin the narrative he wants. NATO should halt expansion and start to embrace a more ambiguous strategy that still allows it to promote security for its members.

Kate Ferrin

With a philosophy rooted in peace and prosperity “with all peoples and all governments,” NATO’s expansion is dependent on the cooperation and communication between the member and prospective states to enact the North Atlantic Treaty’s guiding principles. Any country prioritizing and enacting the Charter of the United Nations should be shortlisted for membership into NATO, and prioritized for expansion, basing the country’s actions towards security and allegiance to member states at utmost importance.

As recent events have shown, this comes with repercussions. When expanding the list of member countries, tensions between prospective members and those independent of NATO must be considered as it likely will come with repercussions for existing members. This is especially pertinent when looking at Russia’s military presence in Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg continually asserts in his (now) daily press conferences that the “tensions [caused by Russia will not be solved] through force or the threat of force.” However, Russia continues to use military force against these borders. It is seemingly significant to recognize that, although NATO is encouraging Russia to reestablish these offices, Russia has cut diplomatic ties with the Organization. Moreover, Russia is not yet willing to enter into dialogue with NATO. So, NATO should shift its focus of expansion to those states willing to cooperate with the values of the alliance.

While Ukraine’s induction into NATO is Russia’s cause for “demand[ing the halt of admission of] any new members to NATO,” the Organization must not succumb to those unruly demands of Russia. NATO is already sending aid to Ukraine; member countries are already asserting their support for Ukrainian sovereignty.

Ultimately, if NATO’s support and expansion into Ukraine enforce “stability and well-being in the North Atlantic area,” it is a beneficial move to make. NATO should not fall victim to the coercive approach Russia has opted to take in this scenario.

Liam Brown

It has been just over 30 years since the U.S. Secretary of State James Baker made his famous promise to Mikhail Gorbachev about NATO expansion: “not one inch eastward”. The subsequent decades proved this promise to be empty, as more than a dozen states in eastern Europe have since joined the alliance. But as more nations have sought safety in the world’s largest military alliance, the state of global security as a whole has declined. A rising China is continuing to destabilize the Indo-Pacific, while Russian tactical groups stand poised to potentially scythe through Ukraine.

In light of this, is a larger NATO community the best avenue to curb aggression in a world where military force is increasingly being used to change the status quo? After all, it is Ukraine and not Poland or the Baltic states – NATO members – whose fate currently hangs in the balance. However, an important calculus must be considered by the alliance. In an effort to ensure peace, NATO paradoxically risks the opposite if expansion is not done carefully. Russian involvement in the Crimean Peninsula and Georgia were prompted, in part, by its neighbours’ desires to join the alliance. More broadly still, NATO should not be seen as a ‘fix-all’ for geopolitical hotspots, used to resolve situations of all types well beyond Europe. The possibility of ‘scope creep’ also threatens the integrity of the alliance itself. NATO’s tenet that “an attack upon one is an attack upon all” must hold true, and thus attacks on one must be met with counterattacks by all. While it is militarily, politically, and logistically possible for NATO to counter a threat to its members in Europe, this may not hold true should NATO find itself defending a new member state in Asia, for instance.

This is not to say that NATO states should ‘quit while ahead’, and refuse to admit new members. Indeed, nations who adhere to the core values of freedom, democracy, and a love of peace should continue to be welcomed into NATO. But offering membership outside NATO’s range of credible deterrence should be done with extreme judiciousness. The moment that the alliance’s core promise of mutual defence cannot be met (or is perceived to not be met) NATO risks undoing its sterling legacy. Likewise, admitting members because they are threatened by attack is noble, but risks the profoundly tragic irony of triggering a war in an attempt to prevent it. NATO is one of the cornerstones of our security, and has presided over seven decades of unprecedented peace in Europe. But when considering expansion, especially beyond its titular North Atlantic region, it must do so with a firm understanding of what it is and what it is not.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.

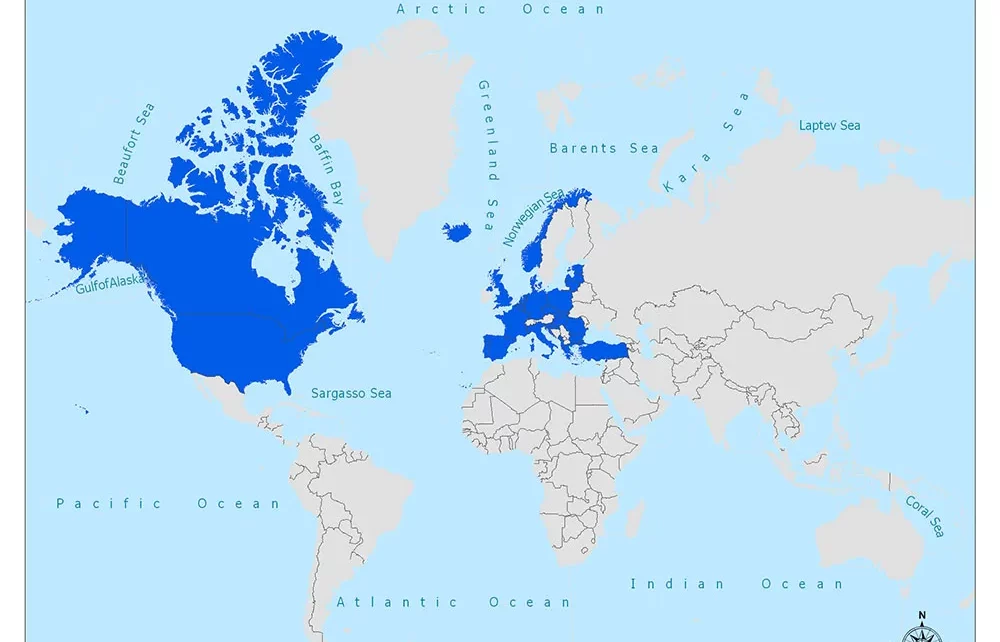

Cover Image: Map of NATO. Found at Mappr.