The recent coup attempt in Turkey initially seemed to be following a script depressingly familiar to observers of the country’s 20th century history. The situation of a disgruntled section of the armed forces, perceiving the government to be trending in a direction counter to the secular founding principles of the Turkish republic, takes over key institutions, rolls a few tanks through the capital and bans the leaders of the overthrown government and their party from the political scene. Since the coming to power in 2002 of the since-ruling Justice and Development Party (or AKP), it had appeared that moderate Islamist and secular forces in Turkey had reached something of a détente. However, recent events have shown that old habits die hard and that at least some section of the military is still convinced of its own traditional role as a check on the wishes of the electorate.

This is despite the fact that one of the largest barriers to Turkish entry into the EU, which nearly every actor on the Turkish political scene at least ostensibly supports, has been repeatedly raised over concerns about the influence of the military on Turkish politics and the general stability of elected governments. It remains to be seen what, exactly, motivated the coup attempt, especially whether the government’s pinning of responsibility on followers of exiled cleric Fethullah Gulen contains any level of truth. Whatever the case may have been, it is clear that its aftermath is empowering some of the worst tendencies of the increasingly authoritarian President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Rightful opposition to the overthrow of democratic governments, Turkey’s status as a major ally within NATO in general and the fight against ISIS in particular, should not distract from a full reckoning with the actions of Erdogan both prior and subsequent to the coup.

This is not to say that any of the problems in Turkey would be have been resolved had the coup been successful. Setting aside the obvious fact that a military-led government would have even less of a reason to respect civil liberties and human rights, many of the worst aspects of the AKP government predate its coming to power, representing a sad continuity in Turkish history. Examples from mass corruption to suppression of political dissidents (including, ironically enough, Erdogan himself at one point) show endemic problems with the AKP. It is, however, the vicious war against Kurdish organizations that is most emblematic of the party’s sectarian tendencies. The AKP-led government has certainly enthusiastically participated in these actions, but it is hardly different from those that came before them in that respect. In fact, a look at the total record of the AKP and Erdogan in power reveals a nuanced, complex portrait of evolving Turkish politics. Namely, that the country’s current leaders, hard though it may now seem to conceive of, once were something of a bright spot in a troubled region.

Taking into consideration his government’s crackdown on opposition media outlets and political parties, in particular the leftist pro-Kurdish HDP, Erdogan still remains widely popular, particularly in the country’s Anatolian heartland. These areas, more religious and socially conservative, have long voted for parties promising varying degrees of Islamic influence in government, and have seen these parties subsequently barred from office prior to the AKP (which contained some members from those previous parties, albeit with a substantially moderated political tone). It is also important to remember that, up until the suppression of the Gezi Park protests, despite its substantial flaws, the AKP seemed to be moving Turkey on a path of greater integration with Europe, sustained economic growth, and a more normalized democratic culture. Many looked to the party and its leadership as models of a moderate, tolerant form of Islam-informed politics akin to European Christian Democratic parties that could provide a viable middle path between secular autocracy and popular fundamentalism in the Middle East. This is not to paint an overly-rosy picture of what came before, but a combination of lust for power, paranoia, and geopolitical stresses have pushed Turkey’s leadership far from this path.

In just the first week following the abortive coup, thousands of Turkish citizens, among them prominent political opponents and independent journalists, have been arrested under flimsy accusations. Erdogan’s rhetoric seems to even further suggest a kind of all-out institutional war on an already-battered Turkish civil society of the type that is unlikely to conclude after only a one-time set of actions. All of this follows from an overall trend towards power centralization and strongman posturing on Erdogan’s part which has only accelerated over time. Some of these, such as the infamously luxurious Presidential Palace, are simply overblown and wasteful, but moves like the removal of an insufficiently loyal Prime Minister over minor disagreements regarding the EU refugee agreement has all the marks of a country devolving into a Putin-esque autocratic pseudo-democracy, t a much more rapid clip than Russia itself. This has been accompanied by a tendency to see wide-ranging conspiracies, particularly those involving erstwhile ally Gulen’s followers, in every setback or criticism faced by the government. In providing some level of justification for this worldview, last week’s events are likely to be seized upon by Erdogan and his followers for a long while to come.

There is still time, however, for something good to come from the recent events. Though a coup should never be cheered, Turkey’s allies, in particular the United States and other NATO countries, could see this as something of a teachable moment as to the risks of the path the country is on. Without peaceful, democratic outlets for dissent and with a government that appears either unwilling or unable to focus its attention on fighting ISIS, rather than the Kurds, this coup or something like it became almost inevitable. EU countries are stuck in a particularly difficult place in bringing any sort of pressure to bear, though, as they require continued Turkish cooperation in order to stem refugee arrivals on their own shores, and are thus unlikely to make too much noise in opposition to what seems to be a widening dragnet operation towards government critics of all sorts.

They may be able to perform more of a slow walk as it pertains to membership negotiations, though given the AKP’s vacillations on the topic, it is far from clear that this would have much of an effect. The United States, and Canada too, are better positioned to apply diplomatic pressure and persuasion, making a case that the coup should be viewed as a warning shot and that Erdogan and his government should retrace their steps back to functional democracy. Many of the citizens who stood up to oppose the coup did so less out of love for the AKP or Erdogan than out of a general desire to uphold democracy and avoid going back to Turkey’s recent past. Leaders both inside and outside of the country should honor this sentiment by adhering to those same principles.

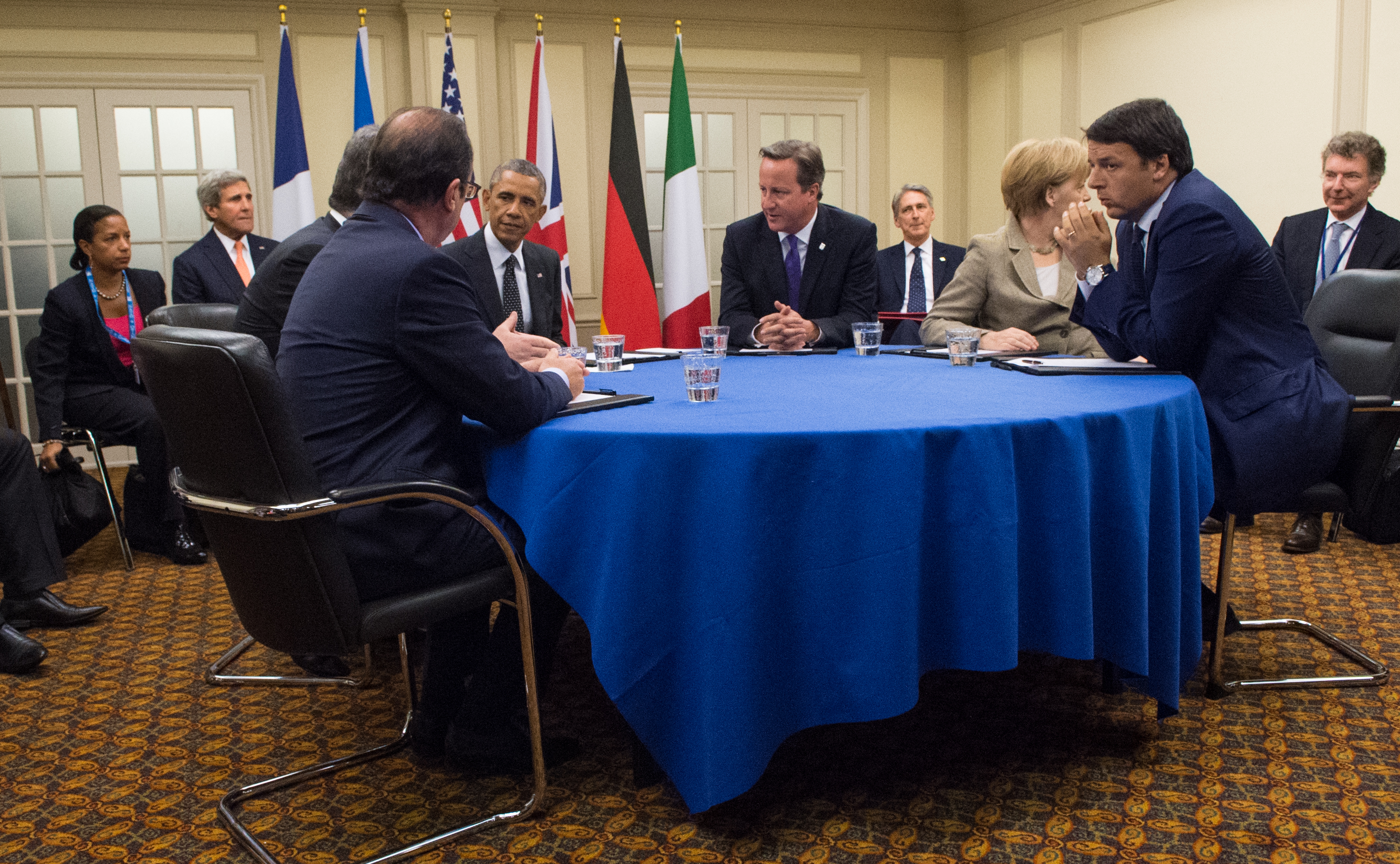

Photo: By the Kremlin via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.