The first two articles in the Investigating Secular Stagnation series looked at how wealth disparity and demographic trends may be contributing to slow economic growth in the industrialized world. The third component, technological advancement in the Information Age, could be the most salient factor of the three.

To reiterate, secular stagnation occurs when savings so heavily outpaces investment that real interest rates are driven down to the Zero Lower Bound (ZLB), limiting the central bank’s ability to stimulate borrowing because it cannot reduce interest rates any further. Low interest rates provide no incentive for new savings in the stock or bond markets, so excess money goes instead into existing assets rather than toward productive investment, which can lead to asset bubbles. The result is higher economic volatility and lower economic growth.

Wealth disparity and demographic shifts contribute to excess savings, but the largest driver of secular stagnation is probably technology’s effect on investment because, as economist Larry Summers puts it, “the new economy tends to conserve capital.” In other words, technological advancements allow us to do more with less. Tasks are now carried out more efficiently than before, but using less material means that less investment is required and more money is saved, reducing the frequency at which money changes hands (known as the “velocity” of money).

Slowing the velocity of money dampens economic growth. To see why, suppose that you and I are alone on a deserted island and start our own economy, so that your expenditure is my income and vice-versa. If you somehow manage to become self-sustaining, I become obsolete and lose the income source that was enabling me to purchase your product. The same principle holds in a complex economy, but now the effect ripples throughout the vast network of buyers and sellers, straining the whole system.

Think about the effect that technology companies have had on the economy. Uber and Airbnb harness the power of digital applications to make better use of existing resources, meaning that fewer traditional taxis and hotels will be built. Online retailers like Amazon and Alibaba diminish the need for physical shopping malls. Digital media giants Netflix, YouTube, and Apple iTunes have killed off their brick-and-mortar ancestors, Blockbuster and HMV. Where we once used paper and photocopiers exclusively, applications such as Google Drive and Microsoft Dropbox allow us to store and transmit most information on “the cloud”. Similarly, multi-volume encyclopedias have been replaced by Wikipedia. All these companies employ technology that obviates material goods, reducing demand in the industries that produce those materials.

Technological progress is understood to be vital for improving productivity, which in turn is central to economic growth. Yet productivity has been poor for over a decade, something economists have termed the Productivity Paradox. If technology is advancing in such marvelous ways, why are productivity and economic expansion not keeping pace?

One theory is that productivity has improved, but that the gains have not been captured in statistics because they are amorphous and difficult to measure. A 2016 study by the Brookings Institution cast doubt on that hypothesis, however. Another emerging idea is that of “zombie firms,” whose uncompetitiveness and poor productivity would have spelled their deaths had it not been for ultra-low-interest credit keeping them alive. If that is the case, the low-interest-rate environment caused by secular stagnation could be fueling a vicious cycle.

A culture of corporate “short-termism” in the business community appears to be a major cause of waning investment. Awash in cash, hundreds of leading companies have repurchased their own publicly-traded stocks to raise their value and appease their shareholders, instead of using those funds toward productive investment. Moreover, large technology companies operate with such low marginal cost that they generate massive profits: in 2016 four of the world’s five most valuable companies were tech firms. In an industry of rapid innovation, a tech firm may sometimes even choose to postpone investment in new technology, lest the product they pour money into developing becomes obsolete by the time it reaches the shelf.

Technological advancement is desirable for the most part. Scientific progress has extended human life and improved its quality in countless ways, and the Internet of Things (IoT) promises to revolutionize life for the better. At the same time, nuclear and biological weapons now give us the means to end most life on Earth instantly, and the IoT carries notable drawbacks for privacy and democracy. Such threats are not intrinsic to technology – human politics created the surveillance apparatus and led nuclear physics to become weaponized, but strictly speaking those regrettable developments were not inevitable.

On the other hand, technology’s link to secular stagnation is a truly problematic paradox. As noted, technological gains have made some leading companies so efficient and profitable that money accumulates in their pockets instead of being reinvested, slowing money’s circulation through the economy. That is an unprecedented conundrum because greater efficiency, though beneficial in obvious ways, is the very source of the difficulty. Just as we invent new technology, solving this puzzle will require innovating the way that we contemplate economic dogma, and will likely force a concomitant shift in our political ideology in order to justify the practices needed to adapt accordingly.

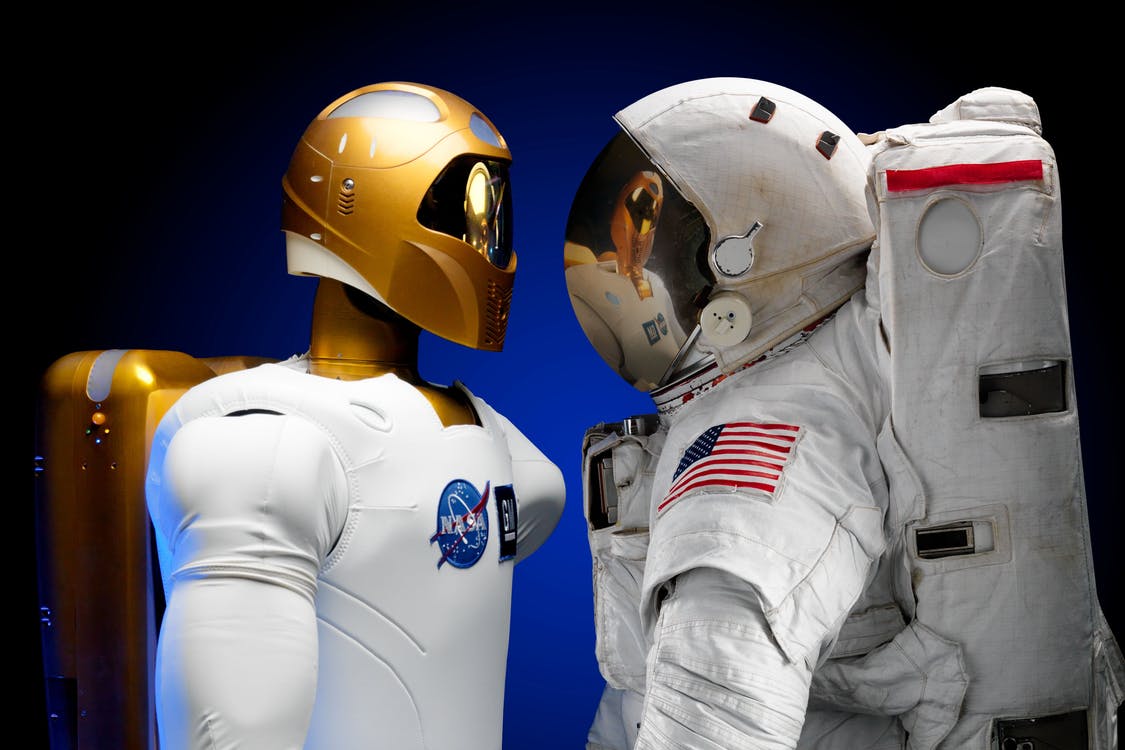

Photo credit: Robot and Austronaut (Date not available) via Pexels. Licensed under Public Domain.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.