When Canadians travel abroad sporting backpacks adorned with maple leafs, they are generally met with warmth and welcome. In my travels, regardless of the nationality of the individual, the word ‘peacekeepers’ seems to inevitably accompany a discussion of the international perceptions of Canada. Though undoubtedly there is truth to this noble portrayal of Canada and the Canadian Forces, it however fails to encompass a more modern and accurate picture of Canada’s defence spending and commitments.

[captionpix align=”right” theme=”elegant” width=”200″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/pearson.png” captiontext=”Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957″]

This disconnect has its roots in what some have dubbed the ‘golden age’ of Canadian diplomacy: Lester B. Pearson’s years as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and as Prime Minister. This era resulted in the peaceful resolution of the Suez Canal crisis, wherein the concept of UN Peacekeepers, fostered by Pearson, was born and which won Pearson the Nobel Peace Prize. Pearson’s other achievements include the ‘Canadian’ Article II of NATO’s treaty, which effectively increased NATO’s capacity beyond that of a mere defence treaty. Article II created a space for economic, social, and diplomatic alignment between member states, and provided the space for significant Canadian influence in multilateral affairs.

Pearson also kept Canada out of the Vietnam War, which set a precedent for Jean Chrétien’s similar refusal to join the ‘Coalition of the Willing’ in Iraq in 2003. Additionally, and on American soil, Pearson vocally opposed the bombing of Vietnam, calling for a pause in violence in order to consider a diplomatic resolution of the crisis. Pearson’s staunch promotion of the UN and its principles of peace led to his two nominations as secretary-general (though he was twice vetoed by Russia).

[captionpix align=”left” theme=”elegant” width=”350″ imgsrc=”http://natoassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/numbers.png” captiontext=”Canadian Contributions to Peacekeeping Efforts”]

Pearson’s legacy has left both Canadians and the international community with the slightly out-dated view that Canada is an international leader in the promotion of peace and peacebuilding operations. Paradoxically, Canada now ranks ninth worldwide in our financial contributions to UN Peacekeeping, at 2.9% of the overall budget. By contrast, the United States and Japan each contribute 28.38% and 10.83% respectively. These numbers accurately reflect each state’s national GDP, but it does assert that Canada is by no means a global leader in peacekeeping as was once the case.

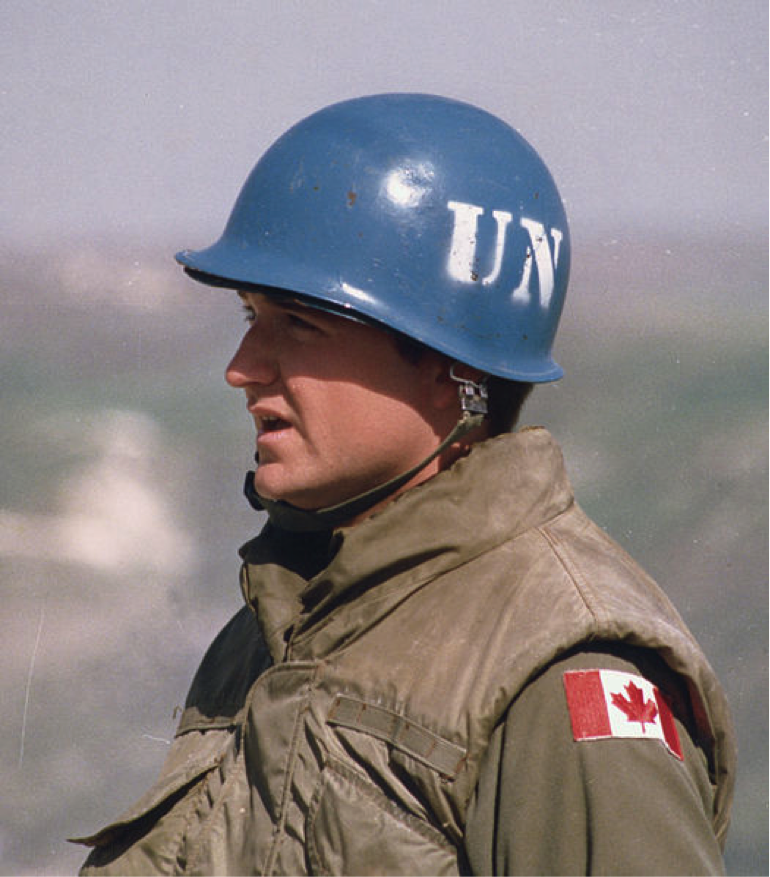

Canada has contributed fewer and fewer troops to UN Peacekeeping Missions. In fact, as of 2012, the UN has registered only 33 Canadian military personnel in UN peacekeeping missions, ranking Canada as the 53rd highest troop-contributor to UN peacekeeping missions worldwide. This is not to suggest that peacekeeping missions themselves have declined – far from it. Currently, there are 15 peacekeeping operations and one special political mission run by the UN, including over 100,000 peacekeepers from various nations.

Interestingly, a 2010 poll shows that a slight majority (53%) of Canadians believe peacekeeping should be the Canadian Forces’ top priority. With only 33 traditional “peacekeepers” in the field, it can be stated that public opinion in this instance is suffering from a serious disconnect from public policy.

There are two important practical reasons for the decline in Canadian peacekeeping efforts in recent years. Firstly, Canada’s heavy involvement in NATO’s ISAF reduced the number of personnel available for peacekeepers. Secondly, a significant amount of the UN peacekeeping is going on in Africa, where the African Union takes the lead, and often, Western faces are less welcome. Despite this, Western forces of recent years have provided significant support in terms of planning, logistics and aircraft support, in which Canada has participated.

Perhaps our notion of peacekeeping has evolved along with the changing face of international politics. ‘Traditional’ peacekeeping missions – brokering disputes between warring states – are no longer the norm in international politics. Today’s world is plagued with an increased number of civil wars based on sometimes hundreds year-old grievances, and are not as easily solved as perhaps in previous years. Furthermore, the world may be suffering from a ‘UN’ fatigue; the UN’s failures come easily to the minds of Canadians: Rwanda, Darfur, Syria… the list goes on. Canada, through NATO, has managed to engage militarily with the overarching goal of global peace, even if it does mean bypassing the UN on occasion (such as in Kosovo).

Maybe NATO has been and will continue to be the future of peacekeeping in Canada. Article 1 of NATO’s treaty states that NATO’s mandate is to “settle any international dispute…by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security and justice are not endangered”. Otherwise, it is only a matter of time before Canadians and the international community at large wise up to the realities of current Canadian peacekeeping efforts.