This essay addresses the link between women’s rights and the notion of R2P in a conflict/ post-conflict situation.

The International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) put forward the concept of Responsibility to Protect (R2P) in 2001. The purpose of this concept is to shift the understanding of sovereignty from ‘control’ to ‘responsibility.’ Thus, states are no longer entitled to control their internal actors; they have the primary responsibility to protect people from crimes against humanity. The second purpose is to recognize that if a state is unable or unwilling to fulfil the mandate, the primary obligation will shift to the international community. The concept of R2P was further extended in 2005 following acceptance of the recommendations of the Secretary-General at the UN Millennium Summit, formally recognizing the basic concepts of human rights, rule of law and collective security against crimes against humanity.

R2P is expressed on a non-gender basis due to the failure of the ICISS to adopt a gender-sensitive approach. Recognizing gender sensitivity would have been proper, given the fact that R2P is conceptualized to prevent atrocity crimes mostly conducted against women and children during war and civil unrest. Further, having different measures based on gender sensitivity would also lead to a more accurate recognition of the status of people who need protection and the urgency of intervention.

However, in 2009, Secretary-General Moon, elaborating the operation of R2P, addressed the need for special protection of women’s rights under the R2P, reiterating that any sexual violence, including forced pregnancy and slavery, should be addressed as a war crime, and a form of crime against humanity. This was the first discussion of gender sensitivity in the context of R2P.

Globally, the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda was illustrated in UNSC resolution 1325 in 2000. The purpose of this agenda was to identify women who are specifically threatened and excluded from the political process and to distinguish the atrocities that are uniquely experienced by women during war. Further, the agenda prescribes the responsibility of the state and the role of international regional organizations to ensure women’s participation in preventive action and representation in the political and peace-building processes.

This essay argues that the first phase is to protect women from atrocity crimes. It is imperative to get women’s perspectives, since, within the four crimes set out in R2P 2005, three defined in the Rome Statute (genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity) have provisions for acts of violence that can be targeted particularly against women. The idea of sovereignty as responsibility reinforces the idea that states and the international community should work individually and collectively to prevent mass atrocity crimes, shifting the security focus from state-centric to human-centric. As R2P focuses on prevention, it provides an opportunity for state actors and other agencies to integrate women’s leadership into the field as a WPS agenda.

The civil unrest in the Democratic Republic of Congo is an example where sexual violence was used as a tool of war against women. Thousands of women were systematically raped by the combatants, even after the end of the war in 2003. This prompted the international community to pass resolution 1820, which states that “rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute a war crime, a crime against humanity, or a constitutive act with respect to genocide.” Further, the resolution required that “all parties to armed conflict immediately take appropriate measures to protect civilians, including women and girls, from all forms of sexual violence.”

In this context, this essay suggests that recognizing WPS while implementing every phase of the implementation of R2P is necessary to address atrocities against women during and after conflict. The first phase is an early warning, where the gender-sensitive indicators must report how targeting of women for specific violence might contribute to instability and insecurity. The second phase of R2P is prevention. Prevention includes the capacity building of women and the encouragement of women to participate in political life. Third would be the Security Council response, where UNSC must have the responsibility to take timely and decisive actions.

However, this essay also recognizes the challenges that affect the integration of women’s rights, in particular, into the R2P framework. First is the inadequate distribution of resources because women are often vulnerable and under-represented. Second, women are often considered as a minority in the formal peace process. Third, as of yet, there have been no gender-specific indicators in the early warning systems. Fourth is the complexity in handling legal issues, particularly with respect to crimes against women, since the Rome Statute identified rape as the only law-breaking crime to be considered a war crime.

Based on the above analysis, the essay concludes with the following recommendations. First, although both R2P and WPS have been understood as complementary actions, since the protections have been recognized inclusively, addressing the rights of women in war zones is imperative for an effective peacemaking and rebuilding process. Further, it is also important to recognize women as positive actors and putative agents under WPS, in recognizing prevention, protection, and participation (3Ps) of the R2P. Further, the increasing recognition by the UN and other state actors of the synergy between the R2P and WPS agendas should be welcomed and acted upon.

Governments and international actors should fund more capacity-building programs, and women should be encouraged to participate in political life. Women’s participation in political life as mediators, utilizing the resources to create safe spaces for women, should be addressed to further enhance the development of a gender-sensitive approach to R2P. Gender-sensitive indicators and early actions through diplomatic channels and other nonviolence forms, and action-oriented research to investigate why such actions fail to protect women in armed conflict should be prioritized. Lastly, a working group on women and R2P to integrate a gendered approach in the implementation of the conception of R2P must be established.

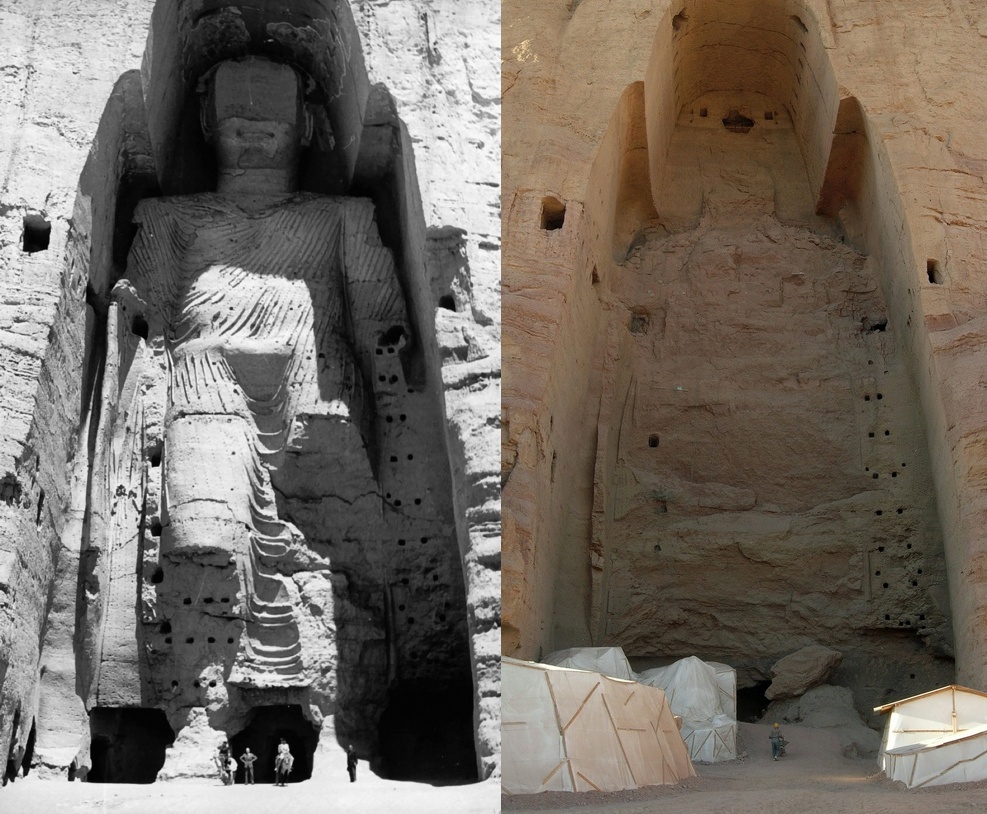

Photo: UN Blue Helmets, by UN Women via Flicker.

Disclaimer: Any views or opinions expressed in articles are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NATO Association of Canada.